For 30 days in 1914, Dr. Anthony J. Lanza, an assistant surgeon of the United States Public Health Service, joined Edwin Higgins, a mining engineer from the Bureau of Mines, in a special investigation into the pulmonary problems of miners in the West visited the lead and zinc mines of Joplin and the surrounding area, spoke with miners, mine owners, and the widows of miners. They studied the mines, the process of mining, and the sanitation practices both above and below ground. Their goal was to understand why miners were seemingly dying in the prime of life from what appeared to be tuberculosis or something very similar to it.

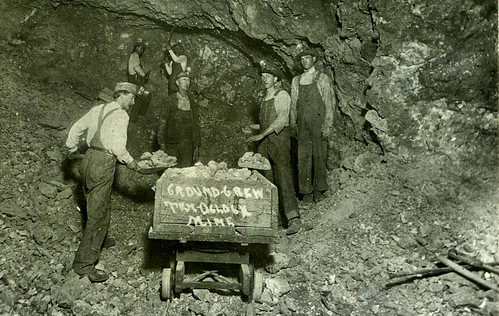

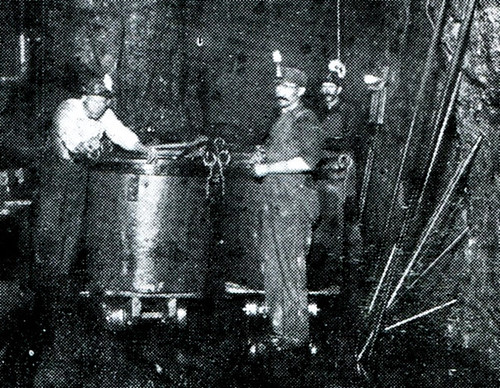

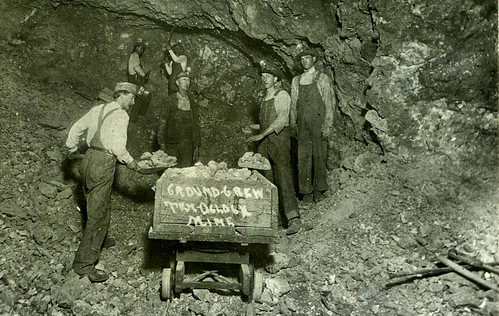

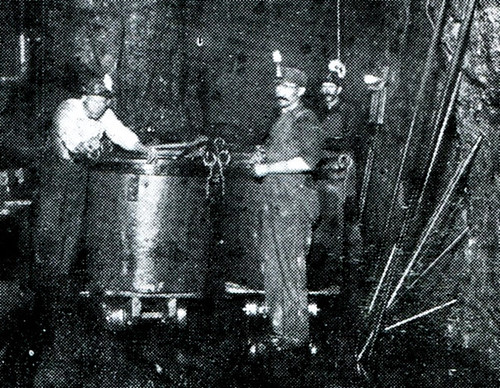

Shovelers filling a cart instead of the usual bucket.

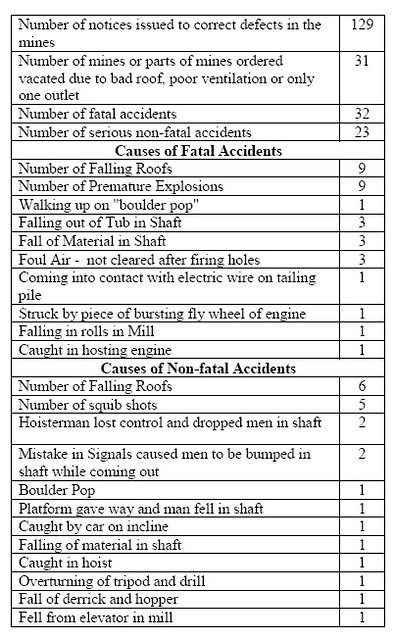

The “miner’s consumption” appeared at a frightfully high percentage of the miner population. In figures provided by Lanza, the doctor noted that of the 1,215 deaths in the general population of Jasper County in 1911, 180 of them were from tuberculosis. This meant over 14% of those who died did so from the pulmonary disease. In the next two years, the percentage grew to 15%. From 1911 through 1913, Jasper County lead the state in tuberculosis deaths.

An organization established to track the disease amongst miners, the Jasper County Antituberculosis Society, offered even grimmer statistics. In 1912, 720 miners died of a pulmonary disease who had worked two or more years in the mines. Some of these deaths occurred outside of Jasper County, as miners had moved elsewhere in the vain hope of better health conditions. Mine operators, whom Lanza spoke with, estimated anywhere from 50 to 60% of their men suffered from some kind of lung trouble. One operator offered the frightful story that over a four year period he had employed 750 men in the mine. Of that number, only 50 remained alive and of the 700 who had perished, only a dozen had died from something other than a pulmonary disease.

Freshly blasted ore waits to be shoveled into a nearby waiting bucket.

Lanza opted to physically examine volunteers in Webb City and Carterville with 99 miners stepping forwarded for the free health exam. Of the 99, 64 suffered from obvious symptoms of pulmonary disease. Of that 64, 42 continued to work below in the mines. Lanza believed that the best way to understand why the miners of Jasper County suffered such high rates of pulmonary disease, he would need to understand the basic aspects of lead and zinc mining in the district. As a result, his report includes a detailed summary of how the valuable ore was mined.

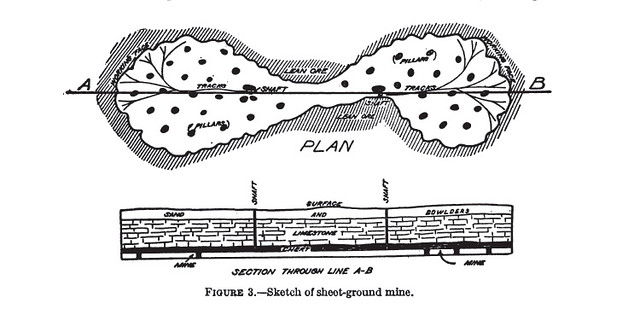

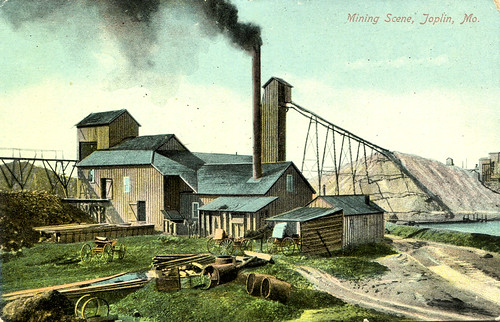

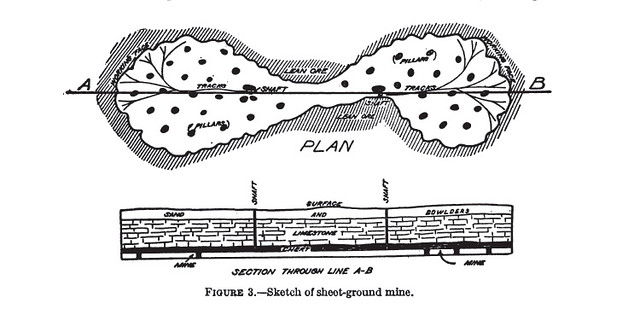

In 1913, approximately 5,988 men were employed in the mining industry in Jasper County, and of that number, 4,242 were miners. They mined 226,738 tons of ore of a value of 9.75 million dollars. With regard to the geology of mining, the ore was generally found in two locations. In sheet ground deposits, on average 180 feet beneath the surface and in irregular pockets, mostly in limestone, which were found at usually shallow depths (such as the discovery of ore during the construction of the Joplin Union Depot). In Lanza’s study, the doctor focused on the former.

A typical mine began with the sinking of a shaft to the depth of the ore. Once it was established, the mine eventually resembled one giant chamber composed of multiple support pillars within a fan shaped area. The pillars were essentially ore that wasn’t mined, ten to twenty feet wide, and left at intervals from twenty to a hundred feet. The space between the pillars was dictated by the quality and composition of the surrounding stone and ceiling. Lanza commented that at the time of the study, the average practice was from forty to sixty feet apart. As mining itself took place in drifts, and the drifts ultimately became interconnected, and it was the support pillars which offered a means to identify one drift from another.

On top, an overhead perspective of a mine. On the bottom, a demonstration of the depth of a mine.

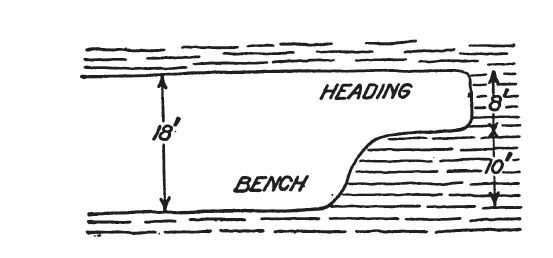

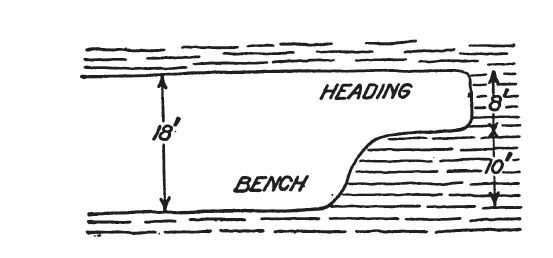

The area actually mined was essentially the wall of the drift which was referred to as the face. Miners either worked the face vertically, keeping the face uniform from the ceiling to the floor, or if the size of the ore deposit was large enough, used a “heading and bench” technique. This practice involved mining deeper into the face for several feet down from the ceiling and then letting a “bench” or “shelf” to be created below it where the mining allowed more of the face to extend outward.

Diagram of Heading and Bench approach to mining the face of the mine.

The mining itself was accomplished by drilling into the face, inserting dynamite into the drill holes, blasting the face, and then shoveling the ore freed from the wall into a bucket to be sent up to the surface. Drilling was almost always accomplished through the use of an air powered piston drill operated by two men, a driller and a helper. When drilling into a regular face, the drilled holes were on average eight to ten feet in depth and the drill was set on a pedestal. When drilling into the heading the drill was usually set on a tripod. The drilled holes were six to eight feet in depth, and when drilling into the “bench” part of the face, could be up to eighteen feet in length.

The process of loading the drill holes with dynamite was known as “squibbing.” Anywhere from 1 to 75 sticks of dynamite were used to “squib” the holes and the actual blasting (also referred to as squibbing) usually occurred at lunch time, while the miners went off to enjoy their meals. However, squibbing could happen at any time, even with miners still in the mine (though at a safe distance from the blast). A minor form of squibbing occurred when drills became slowed or stuck due to debris clogging the drill in the hole and small amounts of dynamite were set off to clear the hole. Sometimes further blasting was also necessary when boulders were produced by the blasting process, too big to be smashed by sledge hammer. Blowing up a boulder was referred to as “boulder popping.”

Three miners pose by a drill.

Once the ore was reduced to blasted rubble, the men moved in with shovels and loaded buckets, commonly called “cans.” Each can held between 1,000 to 1,500 pounds of “dirt.” Once loaded, the miners pushed the heavy bucket to a switch known as a “lay by” where it was then placed in a truck (not the automobile kind) and moved by mules or miners to the shaft. At the bottom of the shaft awaited the “tub hooker” who hooked the loaded buckets to the bottom of a steel rope (often ½ to 5/8ths in width). On the other end of the rope was a geared hoist powered either by electricity or steam. The operator’s seat was positioned so he could look directly down the shaft below. Carefully the bucket was raised to the top of the shaft, dumped, and then lowered back down without every leaving the rope it was attached to, ready to be put back into service.

Lanza, after addressing the process of lead and zinc mining, turned his attention to conditions in the mines. He discovered that mines with two or more shafts generally had good ventilation. The larger the mine, the better the air, and Lanza commented that at least in the Webb City and Carterville area, due to interconnected mines, men could walk for several miles without ascending to the surface. Interestingly, the doctor also noted that the mines used very little in the way of timber, which in other mines was often a source of carbon dioxide.

On average, the temperature in the mine at the working face ranged from 58 to 63 degrees Fahrenheit. Though, these temperatures were gathered at a time Lanza said was seasonally “ideal” and he believed the temperatures would be more severe in hotter months.

Water was a constant source of irritation for miners and in varying degrees. In some mines, pumps were required only to remove a few gallons. In others, as much as 1,500 gallons a minute had to be pumped out of the mine. The water contributed to high levels of humidity, but unfortunately as discovered, did little to reduce the amount of dust the process of mining produced and tossed into the air to be inhaled by the miners.

The dust came from many sources, drilling, blasting, popping boulders, and even a process of clearing drill hose by blowing out dust with powerful blasts of air. Nor did the dust immediately settle once disturbed, but had a tendency to fill every part of the mine and simply remain suspended in the air for a considerable amount of time. Enough dust was created by shoveling the ore, unless the ore was wet and Lanza commented that shovelers sometimes preferred to shovel in pools of water when available. However, this was done because the water loosened the dirt up, not as a precautionary measure against the airborne menace.

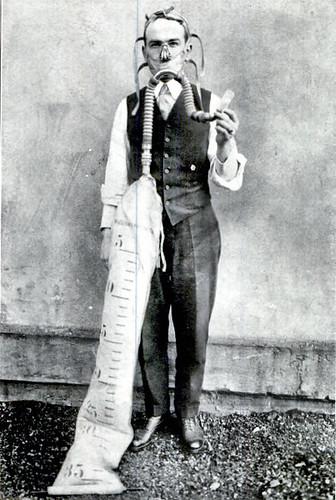

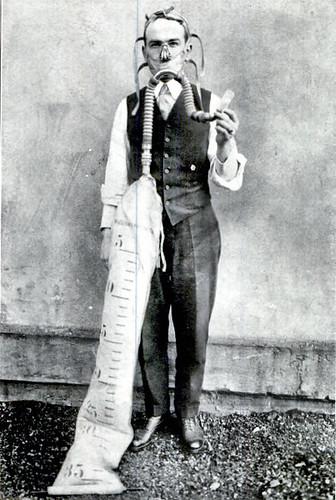

The dust collecting apparatus.

In order to measure the amount of dust particles in the mines, Lanza introduced a dust gathering apparatus worn over the mouth. The device collected dust by intercepting it as it was inhaled through a glass bulb and then the exhaled air was collected in a special bag. The method to devise the amount of dust per breath was performed by measuring the amount of captured dust in the bulb against the amount of air breathed (exhaled) into the bag.

It was discovered that the dust in the Joplin district was much lighter than that found in mining locations around the world, including England and South Africa. This meant that the dust was more likely to linger in the air longer than in other places. The dust particles were also made up of flinty chert, which had splintery and knife-like edges perfect for destroying lungs. These attributes then combined with a mining practice which exacerbated the impact of these qualities. The mining was done in large open chambers, versus more confined spaces. This allowed for a greater dispersal of the dust.

Lanza made a number of recommendations to reduce the amount of dust in the air. First, implement drills that used water to wet down the face at the same time as drilling. If that type of drill was not available, then at least the provision of a hose to water down the face of the mine. Second, stop squibbing (blasting) and popping boulders while miners are still in the mines. Third, improve ventilation with new shafts.

Miners stand by two filled buckets and are surrounded by boulders likely to be "popped" in the near future.

The doctor’s study was not restricted to just dust, but to other contributing factors to high rates of pulmonary disease. Among them, sanitary conditions in the mines, or as Lanza discovered, the lack thereof. On average, most mines employed between 25 to 30 men, and while privies were established on the surface, there were none in the mines. Despite a rule against “ground pollution,” Lanza noted that there was “much evidence of this abuse.” In conclusion, he reported that “wretchedly insanitary privies are only too common everywhere in the district.”

Drinking water was also a concern. In some mines, a keg of water with a common drinking cup were found. In others, simple upturned spigots were provided. What both had in common, to the investigator’s dismay, was the ease by which germs could be spread mouth to mouth by thirsty miners. In small mines, Lanza believed the best solution was for every miner to bring his own water down for consumption.

Above ground, an innocuous problem existed. The failure of miners to use change houses, places where they could change out of the clothes from the mines into a set of clothes clean of the ever present dust. Instead, the miners often preferred to go from the mine straight to town. Another issue involved men coming out of the mine with wet clothes from the moist conditions, and then heading off in cold weather. Eager as the miners were to be done with their underground work, Lanza discovered many took lunches (dinner) for only 20 minutes, eating quickly and returning back to work so as to leave sooner in the evening. This short lunch deprived the men of the needed physical rest and made them more vulnerable to sickness and other physical ailments.

Beyond the working conditions and practices, Lanza focused on the system itself in how miners were paid and worked. Shovelers, he found, were paid by the “piece.” This meant for every can (bucket) of ore they filled, they were paid between five and eight cents. Every bucket’s capacity, in turn, averaged around 1,000 to 1,650 pounds. Experienced shovelers made between 3 to 5 dollars a day. By the application of quick math, this means that on a daily basis, shovelers moved at the least 60,000 lbs of ore/dirt a day to at least a staggering 93,750 lbs a day. Many of the shovelers were young men, who began around the age of 18 or 19, and initially could fill between 60 to 70 cans a day. Some claimed that there were miners who even filled over a 100 cans, which meant over 100,000 lbs. It was back breaking hard work and of the kind that gradually broke the men physically. Within two to six years, the shovelers’ output declined and their daily capacity was reduced to around 35 to 40 cans.

Young men often were shovelers, enjoying a job that paid well but demanded backbreaking and dehabilitating work.

Lanza included a grim timeline of the decline and death of a shoveler in the mines, here quoted in its tragic entirety:

“After a few years of shoveling, the shoveler finds himself beginning to get short-winded and his strength failing. When he comes to the point where he feels exhausted at the end of his day’s work and feels “groggy” when he starts in the morning, he begins to rely on alcoholic stimulation to see him through, and if it has not already done so, alcohol now begins to lend a hand in furthering physical breakdown. The next step in the process is tuberculosis infection, and when the shoveler finds that he is no longer able to make a living shoveling, he gets work as a machine man or machine helper. He finally becomes unable to work, and as these men usually work as long as they possibly can, death follows not long after cessation of work, most often when the man should be in the prime of life. Usually a fair-sized family is left behind and is apt to need charitable assistance”

Lanza concluded, “Although this sequence of events has not occurred in every case of fatal illness among miners, it is fairly typical of a great many.” His only solution was to prevent young men from being employed as shovelers in hope that the few years prior to engaging in the practice might mean more years later to live.

Lastly, Lanza directed his attention toward the homes of miners above ground. There he found that many families dwelled in two to three room “shacks,” often without water and only as clean as the circumstances allowed. Commonly, the shacks were rented, though for a low price, within the area near the mines. They were “of the type most readily associated with poverty and disease.” Drinking water came either through barrels supplied and drawn from deep nearby wells, or if the homes were within the city limits, then provided by the city through piping. Lanza lamented what he perceived to be spendthrift habits amongst the miners, and stated he believed most were all too ready to spend the money they earned, rather than save for the future. The result, when pulmonary disease struck and the men became unable to work, or work as well, the families quickly became destitute.

His investigation of the Joplin mining district over, Lanza summarized what was discovered. The death rate from pulmonary disease was unusually high for the district. Alcoholism, use of common drinking receptacles, poor housing, exposure and over work, helped to spread infection and lower resistance. The number one reason for the high rate, Lanza believed, was the impact of the dust, which miners were exposed to nearly every minute of their shifts, and the composition of the dust as sharp and knife-like.

Miners stand by multiple empty buckets, possibly the lay by area. Note the hooks on the buckets for hoisting to the surface.

The doctor believed that the problem the dust posed could be eradicated almost completely by the use of water in the drilling process, improving ventilation, and making sure miners were not in the mine when blasting or squibbing was performed. Health problems could also be further alleviated by not employing men under the age of 20, by providing drinking sources which weren’t communal, a limit on the daily tonnage shoveled by miners, education to miners and their families on better health practices, and providing warm, dry places for miners to change after their shifts.

Lanza’s study of the Joplin mining district was part of a growing concern in occupational safety, be it in factories in the great northern cities, or in the mines of Southwest Missouri. At this time, we can’t speak to the immediate impact of the study on the Joplin mines, but if for nothing, the study provides a capture of what mining lead and zinc in the Joplin district was like and the dangers that it poised to its miners.

Source: Pulmonary disease among miners in the Joplin district, Missouri, and its relation to rock dust in the mines,” by A.J. Lanza, Google Books for diagrams and image of dust collecting apparatus.