Lead and zinc mining was the heart and soul of early Joplin. Men toiled in the mines to earn their living or, in many cases, meet their end. There were a variety of ways that death came to those who worked in the mines, often sudden and very violent.

On June 13, 1901, the Carterville Record reported that T. Hibler, a mining engineer working in nearby Galena, fell into a mine shaft over one hundred feet deep while walking to work at 5:30 a.m. Perhaps it was simply luck, or maybe the manner in which the unfortunate engineer tumbled downward into the darkness, but Hibler survived the fall. Not only did Lady Luck spare his life, but shortly after, a passerby came to his rescue. Amazingly, Hibler suffered only a few cuts, bruises, and a sprained ankle. He was one of the fortunate as others were not so lucky.

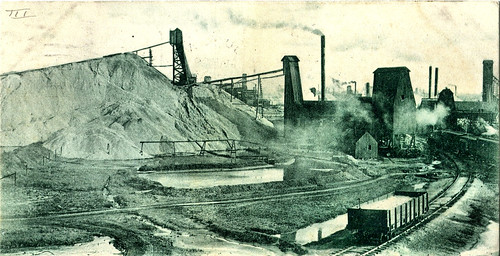

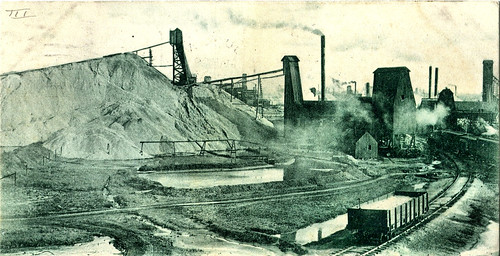

A mine with chat pile looming beside it.

In James Norris’ “AZn: A History of the American Zinc Company” he noted that “In 1897 soaring prices and continued active demand produced large profits for miners in the Joplin zinc-ore district, and the following year was one of the most prosperous in the history of zinc mining.” This boom in lead and zinc mining attracted the attention of wealthy Eastern investors. In 1899, a group of Boston capitalists formed a corporation they called American Zinc, Lead, and Smelting Company. American Zinc, as it was commonly known, became one of the major players in the Tri-State Mining District.

In 1902, Harry S. Kimball was sent to Joplin to evaluate the company’s prospects in Joplin. He later recalled that Joplin was a, “bleak prospect for a tenderfoot to see as his first contact with a mining camp.” Hugh chat and slag piles littered the landscape. Miners were using “relatively simple and inefficient” mining methods. Thus men who were on the cusp of a century that heralded rapid technological and industrial innovations were operating as if they were still in the Dark Ages.

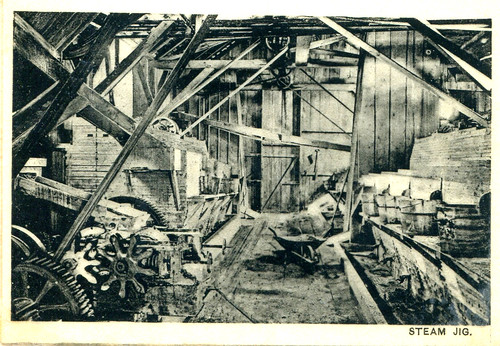

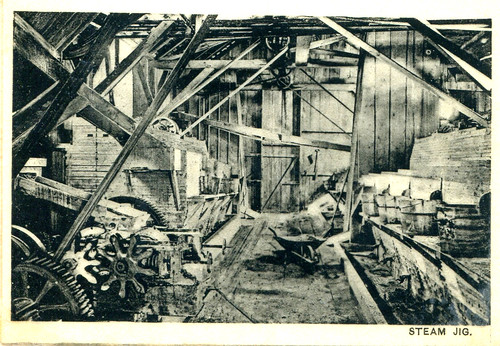

An example of the primitive technology at play in the mining fields. Here a hand-powered jig.

Historian Arrell M. Gibson describes the various mining techniques used in the Joplin area in his book, “Wilderness Bonanza.” Shafting, which required miners to create a vertical access shaft into the earth, was dangerous work. Miners drilled openings into the rock face and then inserted sticks of dynamite into the holes in order to break up solid rock. Dynamite, if handled incorrectly, was deadly. Miners sometimes had to tamp sticks into place. This involved tapping the explosive material into a firmer or deeper position. If they neglected to use a wooden stick to tamp in the dynamite, often using a metal bar instead, it could create sparks and cause a premature explosion with devastating effect.

Adding to the danger, miners also used giant powder, which was more powerful than regular black powder, to break up solid rock surfaces. Gibson states that many miners complained that giant powder caused headaches and nausea. But if a miner was fortunate enough not to die in a mine collapse, premature explosion, or suffocate, there was a good chance he would die early from silicosis. Silicosis is a condition caused by breathing in crystalline silica dust. After a controlled explosion, miners often failed to wet down the rock and as a result, inhaled minute particles of rock dust, which damaged their lungs like invisible razorblades piercing through their lung tissue. Miners who suffered from silicosis experienced shortness of breath, coughing, fever, and even a changing of the color of their skin. Of the many miners who eventually succumbed to the manufactured disease, one was Oscar C. Rosebrough. The thirty-six-year-old miner died of “miner’s consumption” in the summer of 1917.

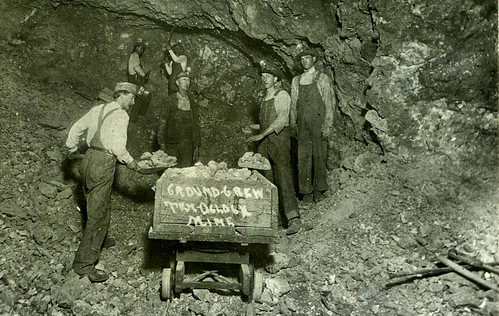

Miners posing for a photograph within the dangerous confines of the mine.

Other deaths came suddenly and mercifully for some. The Carl Junction Standard reported on September 12, 1903, Walter McMahan was telling jokes and laughing with his coworkers at the Edith Mine near Joplin when a large boulder fell from the mine roof and crushed him. Meanwhile, The Carthage Evening Press recounted the death of Riley Marley, who was killed when he and his partner set off two shots of blast in a mine shaft. When one of the shots failed to go off, the two men reentered the mine to re-tamp the shot. As Marley tamped the shot back into place it exploded and drove the tamping rod through his head. He died instantly. His partner was blinded by the blast but survived.

Much of the danger came from simply entering the mines or processing areas. In 1905, Nathan Rice was struck on the top of his head by a falling timber. He later died of his injuries. In 1916, John Campbell was killed when he got caught in a drill rig. In 1882, Johnie Craig died when he went into a mine contaminated by bad air. In 1920, Kenneth Everett, a five year old child, died from bad air in an abandoned mine shaft.

Far more complex than the hand jig, it's not hard to understand the danger of working around this steam powered jig.

Close calls were common and sometimes bizarre. In 1902, William Morgan was injured while working in the Big Six Mine when an icicle fell from the top of a mine shaft and hit him in the back. The icicle was heavy enough that it fractured his shoulder blade, but the physician who tended Morgan expected his patient to recover.

The zinc and lead of Joplin brought great wealth to some, work to many, and danger to all who entered the mines to retrieve it.

Sources: “Mine Accidents and Deaths In the Southwestern Area of Jasper County, Missouri, 1868-1906,” Volume I. Compiled by Webb City Area Genealogical Society. “Mine Accidents and Deaths In the Southwestern Area of Jasper County, Missouri, 1907-1923,” Volume II, “Accidents, Deaths, and Other Events.” Compiled by Webb City Area Genealogical Society. “Wilderness Bonanza” by Arrell M. Gibson