The Wright Lead and Zinc Company of Chicago, Illinois, was one of hundreds of companies that sought shareholders to help finance its mining ventures in Joplin. The president of the company, Walter Sayler, was an ambitious Chicago lawyer. A.H. Wilson, treasurer, was partner in a large real estate company and John W. Wright, secretary, was a “mining expert.”

He, along with his fellow officers and directors of the company, sent out circular letters advertising the opportunity to purchase stock in the anticipation that the company would strike it rich in the lead and zinc mines of Southwest Missouri.

The company’s letter must have intrigued a few investors. The stock was said to be a “safe 12 per cent investment; a probable 3; a possible 48.”

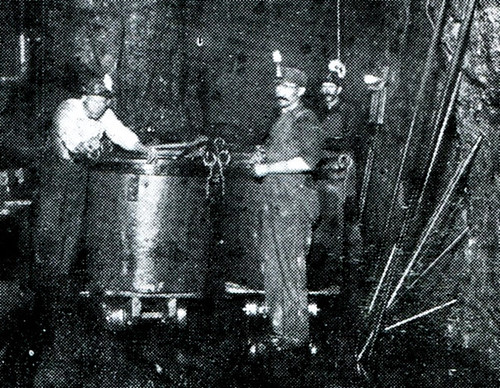

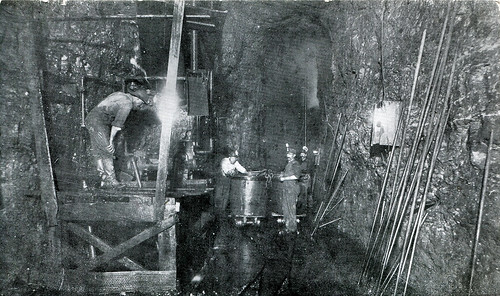

The company owned over 500 acres of land divided between four properties. Wright Lead and Zinc planned to sink twenty shafts across its four properties, and expected to make an estimated $40,000 per month before payroll, royalties, material, and other costs, leaving a $20,000 profit.

In case one might have doubts about investing, the letter included a circular with endorsements from various politicians and businessmen, descriptions of Joplin and mining operations, and a selection of “Tales of Fortune.”

Joplin was described as “utterly unlike any other mining camp in the United States. It is a combination of the east and west, of the north and the south. It is at bottom an agricultural and commercial town, upon which has been superimposed a thick layer of American birth.”

It was in Joplin that one tenderfoot, along with his partner, was seemingly hoodwinked by two seasoned local miners when they purchased a piece of land long thought tapped out. But the two greenhorns, not knowing any better, worked their land and eventually struck a new vein of ore that allowed them to buy a new hoist and other mining equipment. Within a few months, they had cleared $33,000 in profits. Then there was the story of a young man from Kansas City who, with $150 in capital, began work on a modest claim. He found enough ore to build a mining plant which he then used to bring up $30,000 out of the mine.

Even Mrs. M.C. Allen, Joplin’s famous mining queen, was mentioned as one of the mining district’s success stories. Having failed to sell her land for $50 an acre, she leased it, and made a fortune. Intriguingly, after telling of Allen’s success, the circular added, “Among the mine operators of the district are several women, and almost without exception they have done well or have prospects of making large profits in the near future. Their lack of mining knowledge is more than offset by the gallantry of the land owners and promoters, who see to it that the ladies who so pluckily venture into mining are given the best locations and every assistance [sic] possible.”

As the circular noted, “One of the richest men in Joplin was once a bartender; another drove a brewery wagon; others labored in the mines or worked in stores or on farms, and had only their hands to work with. Riches came to the lucky ones.”

But the days of luck were over. Within a few decades the mines of Joplin would stand still, only to fade away, leavening behind faint memories of a proud mining history.