Below you will find Joplin’s finest in 1920. The chief at the time was Joseph Myers and the photograph was taken in front of the old city hall. Behind the large doors behind them would have been stored some of the city’s fire engines.

Current Prospects for the Union Depot

A hotly debated issue silenced by the tornado of 2011, the restoration of Joplin’s Union Depot has quietly started to filter back into the conversation of the city’s future. While the previous discussion was focused on turning the depot into a new home for the Joplin Museum Complex, an idea that the governing boards of the JMC were reluctantly being dragged toward accepting, the new round of talks has removed the JMC from the equation. SPARK is the word now, “Stimulating Progress through Arts, Recreation and Knowledge of the Past,” which is part of the current plan by the city and Wallace Bajjali Development Partners to turn north downtown Joplin into a center for arts and recreation.

As recent articles in the Globe have stated, the new plan for the Union Depot is to renovate it as a home for restaurants, not for the museum. In the current budget of the Master Plan, the city voted in late December, 2012, for the creation of a TIF district which would pay for some of the redevelopment projects, to set aside “$68 million for a performing and visual arts center and Union Depot restoration…” If you were wondering about the JMC, in the same process, money was planned to build a completely new museum home which would be somewhere in the vicinity of north Main Street.

Here at Historic Joplin, while we championed the move of the JMC to the depot, we are just as satisfied with this new idea so long as its implemented and one of Joplin’s most valuable architectural jewels is preserved for future generations.

To learn more about the Union Depot, read our five part history of the depot here: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, and Part V.

Joplin’s Gallant Irishman: Daniel Sheehan

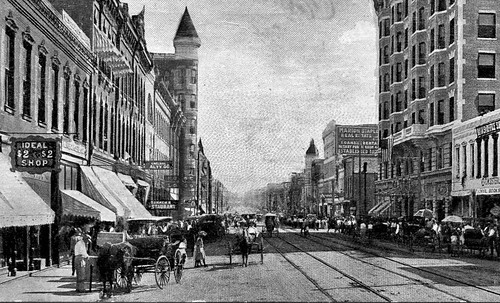

One journalist described the early days of Joplin as nothing more than, “lead, whisky, and gambling.” He went on to elaborate that it was a time when “the faro table was the best piece of furniture and needed legs like a billiard table to stand up under the coin; when the ‘bad man’ was numerous and had a retinue; when the Indian gave daily street exhibitions or archery, and a shooting gallery was a better business proposition than a skating rink today.”

The citizens of Joplin depended upon a small contingent of law enforcement officials who relied upon their knowledge of the community, their instincts, and brute force when necessary to keep the peace. Among those who walked the muddy streets corralling prostitutes and breaking up drunken fights was Officer Daniel Sheehan.

Born in 1830 in Killarney, County Kerry, Ireland, Sheehan was a “very Irish Irishman” who spoke with the characteristic thick brogue of his home country. He had long served the city of Joplin as a night watchman and police officer. Commonly known as “Dad” to everyone who knew him, Sheehan was said to be “inoffensive as a child [and] always had a mirthful Hibernian salutation.” Despite his inoffensive manner, he allegedly never overlooked a dog that needed taxing at a time when residents still paid a dog tax.

During bad weather, Sheehan would stop by the offices of the Joplin Daily Herald and sit by the stove to keep warm. The paper’s founder, A.W. Carson, was fond of the old Irishman and the two men became good friends. It was said that “Carson got many a juicy morsel of ‘inside’ information that pleased in print — and much that was never printed.”

Carson made sure the Joplin’s gallant Irishman played a prominent role in the stories that he printed in the Joplin Daily Herald. Several of the stories cast Sheehan in a comical light, but provide insight into his daily duties, many of which would be familiar to a modern day police officer: Fights, rowdy prisoners, domestic violence calls, and careless and imprudent drivers.

Sheehan was once greatly offended when an “unruly prisoner” called him a “damned Dutchman.” The editor of the State Line Herald lightheartedly proclaimed, Sheehan was “the only Irish scholar in Joplin who thoroughly understands the language. He is also remarkably well drilled in English military tactics, and can handle a company of men as well as a West Pointer.”

In 1883, a young boy ran up to Sheehan and reported a fight taking place between four or five women. As Sheehan approached the residence, he heard “wailing [and the] gnashing of teeth.” Forcing the door open, he sprang inside, but found the house empty. Perplexed, Sheehan searched the house and stopped when he found “three pairs of plump legs” sticking out from underneath a bed. The newspaper reporter cheekily remarked: “A less courageous heart would have quailed confronted by such an array of hosiery, but faithful Dan proceeded to march them off” to police court. Other calls were, unfortunately, much more serious.

On another occasion, an individual’s “obnoxious” and “bellicose” behavior led to the Sheehan searching him. The officer confiscated: a billy club, two dirks, a self-cocking revolver, two flasks of whiskey, a bottle of sulphate of zinc, a vial of balsam copaiba, and a “toy India rubber shot-gun.” The veteran officer “is in a dilemma whether to start a gun shop or a drug store.”

Like veteran officers of the era who had to rely on their instincts and experience, Sheehan was often in the right place at the right time. When a “gilly from Arkansaw fired off a pistol in the alley near Botkins livery stable” Sergeant Sheehan was “as usual around and welcomed the artilleryman with open arms as he emerged from Fourth Street.” The Arkansawyer was promptly escorted to police court.

On a fall day, Sheehan arrested a visitor from Cherokee, Kansas, who was driving his buggy too fast through the streets of Joplin. The Kansan had come over from “his persecuted state for a little recreation on free soil, and very naturally tarried too long at the bowl wand was soon under the influence of ‘corn juice.’” He decided to hop in his buggy for a jaunt down Main Street. He had almost completed his circuit through town when Sheehan arrested him. The newspaper noted that while the man’s lodging cost him nothing, the city received a fine of $16.25 from him.

On other occasions, he found himself taking care of domestic matters: In the spring of 1881, Sheehan shot and killed a rabid dog on Pearl Street that had attempted to attack a family, and on another call, he arrested a man for beating his wife.

The Irishman spent much of his time arresting Joplin’s sirens of sin as this story illustrates:

“The affable gallant Sergeant Sheehan created quite a sensation yesterday in back alley circles of society by escorting a flashily dressed woman along the somewhat contracted thoroughfare lying immediately west of Main Street,. The old veteran had far more opportunity to show his gallantry on this many scented alley than on Main Street. There were ash-heaps to circumnavigate, slop barrels to evade, and a devious way to as to be threated amongst beer bottles, empty oyster cans, and cast-away cat corpses that strew that delectable Golgotha. The Chesterfield of the force performed this difficult act of courtesy in the most satisfactory manner, although his handsome charge seemed faint and leaned heavily on his strong arm. At one or two difficult passages she even pressed heavily on his larboard quarter is as the wont of the gushing miss in her first overpowering attack of puppy love. The veteran officer was marble and evinced none of the weaknesses of frail flesh and blood. With the placid face of devotion to duty he made the passage and ushered his charge, silk-dress, perfumery, six button kids, and all, into the cooler. It was California Kate on her regular drunk.”

Many of the women were under the influence of drugs and alcohol. On a fall day, he “encountered a lewd woman in a beastly state of intoxication in the alley west of Main Street yesterday. She resisted arrested, fought, scratched, and shouted foul epithets known only to her ilk. In her struggle, she tore off the skirt of her dress, but was finally landed in the calaboose.”

Woe to any lawbreaker who angered the old copper after Pat Wynne of Columbus, Kansas, presented Sheehan with a “new official cane. It is of the substantial order of architecture and will be found of full regulation weight when it comes in contact with an obstreperous law breaker.” Sheehan may have well been carrying this cane when, in 1885, he made his final collar.

Over the years, the city newspapers carried varying accounts of what happened on that hot July afternoon in Joplin. The details, provided by eyewitnesses, fellow officers, and citizens who remembered the tragic events, have been gathered here and distilled into a narrative account that provides the reader with an overview of the events of that day, choosing to instead focus on his life, rather than his untimely death.

In the summer of 1884, Joe Thornton began selling whisky in a two room building that sat on the state line of Missouri and Kansas. Because it was illegal to sell liquor in Kansas, he reportedly sold his illicit liquor on the Missouri side of the line, and because gambling was prohibited in Missouri, he set up gaming tables on the Kansas side of his establishment to the annoyance of local officers.

Although he engaged in nefarious activities, Thornton had allegedly never killed anyone, though he had tried. Thornton had once stuck a .45 pistol into the stomach of Lewis Cass Hamilton, one of Joplin’s toughest law enforcement officers, and pulled the trigger twice. The gun fortunately misfired.

On the fateful day of July 18, 1885, Thornton was wanted on five warrants, and although officers had tried to arrest him for months, he had eluded capture. He generally only left his building once a day at noon to get water. Previously, officers had asked a nearby home owner, A.B. Carlin, if they could hide in his blackberry patch and ambush Thornton. Carlin gave his permission, but later changed his mind, fearing that Thornton would take revenge if the officers failed to arrest him. Thornton, unafraid, occasionally visited Joplin on business.

On July 18, 1885, Jasper County Julius C. Miller stepped out of the Joplin post office on the northeast corner at Second and Main and saw Deputy City Marshal Daniel Sheehan standing on the opposite corner. Sheehan alerted Miller that Thornton was in town and said if Miller wanted to arrest him, Sheehan and “Big George” McMurtry would help.

Miller was in a difficult position. He knew that Joplin City Marshal Cass Hamilton had ordered Sheehan to never attempt to apprehend Thornton because Thornton had threatened to kill Sheehan, claiming the old Irishman had once mistreated him. Miller, Sheehan, and McMurtry met at the northwest corner of Second and Main to discuss the matter. Sheehan was insistent that they arrest Thornton and added, “an’ sure all we’s have to do is kape him from gettin’ to his weapon.” The men noticed Thornton’s buggy tied up outside of Simon Schwartz’s dry goods store, Famous 144. The three officers headed toward to the store. Once inside, Sheehan pointed Thornton out to Miller, who had never seen Thornton before. Miller began advancing toward Thornton who had his back turned to the door. Miller tapped him on the shoulder and asked if he was Thornton. Thornton replied that he was. When notified that Miller had a warrant for his arrest, Thornton remained calm, but when Miller said, “Sheehan, take hold of his other arm,” Thornton pulled out his gun and shot Sheehan.

Miller, who was described as six foot tall and “no invalid,” jumped on Thornton and tried to wrestle the gun away from him. Unfortunately, Miller’s hands were near Thornton’s mouth, and bootlegger began savagely biting Miller’s fingers and wrists. Miller could “feel the membrane begin torn from the bone” by Thornton. One of his hands was caught up in the action of the gun and Thornton kept “snapping away and every fall of the hammer was cutting into shreds the skin and flesh between Miller’s thumb and forefinger.” Miller’s tattered hand was the only thing keeping the gun from firing. As one account put it, “Miller had to stand it or leave a widow at home.”

Sheehan, who had been caught up in the fight, realized he had been shot. He cried out, “Oh, I’m shot! Take me out! Take me out!” before he fell to the floor. Deputy City Marshal McMurtry was ordered by Miller to “do something and do it quick. He’s eating me up.” Sheehan, lying helplessly nearby, called out, “Take my club!” McMurtry grabbed the Irishman’s club and began beating Thornton as hard as he could over the head, but accidentally hit Miller with the second blow. Miller yelped, “Don’t kill me, Mac!”

Contractor Sol Wallace and coal dealer W.E. Johnson rushed into the fray and pulled the store’s twin merchandise counters apart so that they more easily help separate the two men. McMurtry continued to strike Thornton in the head which was a bloodied mess. Thornton bit Wallace, but Wallace managed to get a grip on the pistol. When Thornton would not let go, Wallace kicked him in the throat, but the blow did not seem to register. Finally, his adrenaline exhausted, Thornton surrendered.

The four men started Thornton to the door on the way to the jail and were followed by a weakened Daniel Sheehan. The Irishman collapsed in the doorway and was taken to Dr. Kelso’s office. An examination showed that the bullet had entered a little below to the left of the navel and ranged downward and presumably lodged in tissue near Sheehan’s spine. When it became clear that Sheehan had but a short time to live, he was taken to his home. Miller’s hands and wrists were “in ribbons” and he carried the scars of his encounter with Thornton for the rest of his life.

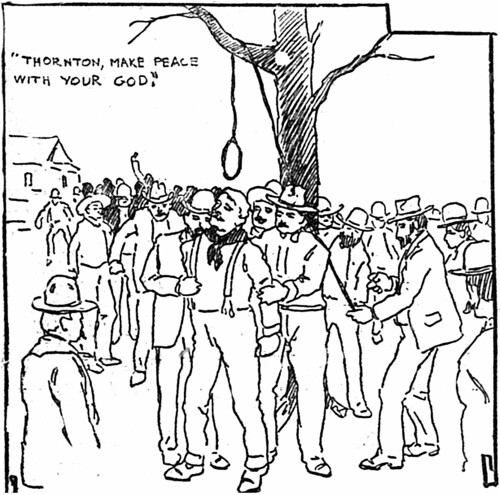

After Thornton was put in jail, a crowd gathered, trying to catch a glimpse of the man who had shot Daniel Sheehan. He talked freely, telling one questioner that he was raised in Parkersburg, West Virginia, and that “I am too lazy to work and too ornery to live. If you want to send me over the road, I’m ready.” When someone mentioned lynching, Thornton reportedly replied, “I deserve to die and if they will bring on the rope, I’ll march out and die game. I don’t want to be mutilated and abused. I’d rather die now than go to the pen.”

News of the shooting spread quickly and a mob began to gather. Shouts of “Hang him!” and “Joe Thornton must die!” could be heard on the streets of Joplin. At two o’clock in the morning, a group of men approached the city jail with a battering ram. With just a few blows, the door was forced open, and the men found Thornton sitting in the first cell. The mob threw a rope over his head and marched to the “Kennedy property” at Second and Main where there were several maple trees. A crowd gathered to watch, but the mob kept the curious onlookers from getting close until they had lynched Thornton. Only then could spectators approach and look at Thornton’s body. He was pronounced dead and the coroner declared he had died at the hands of parties unknown. The Joplin Daily Herald remarked, “Thornton has paid the penalty of crime with his life. A dozen such lives would be feeble atonement for his crimes. Mob law is to be deplored, but great emergencies require desperate remedies.”

Thornton’s mistress, May Ulery, arrived to claim his body. She dressed him in a new suit of clothes before a hearse from Galena arrived to transport his corpse to the residence of his brother in Galena. Thornton was then buried in the Galena City Cemetery. A few weeks later, the building that housed Thornton’s dive was moved from the state line to Galena, Kansas.

Daniel Sheehan died a short time later on July 19, 1885. The fifty-five year old Irishman left behind a widow, Kate, and five children at home, including the youngest, Cecilia, who was one. His family received a free plot from the city in Fairview Cemetery for his burial. The vacancy on the police force was not filled for a month after his death so that his family could receive a full month’s salary by the “kindly arrangement of his brother officers.” Fellow officer McMurtry kept the shell casing from the round that killed Sheehan. The remaining five shells were removed from pistol, a .38 Colt, and distributed as mementos.

The citizens of Joplin were grateful for Sheehan’s service. A subscription fund was started by Joplin Daily Herald editor A.W. Carson to pay for a handsome stone monument from True Brothers & Sansom. Among the more prominent names on the list were Thomas Connor (.50 cents), Thomas W. Cunningham ($1.00), Clark Claycroft (.25 cents), Charles Schifferdecker ($2.00), W.H. Picher ($1.00), and Edward Zelleken ($1.00). Fellow officer Lewis Cass Hamilton gave the most money with a $5.00 donation and Simon Schwartz, owner of the store where Sheehan was killed, donated $3.00.

The handsome marble monument still stands as a testament to an immigrant who made a new life for himself in the rough and tumble mining town of the old Southwest.

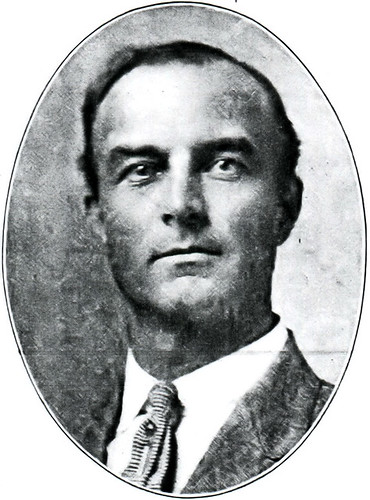

Elliot Raines Moffett

On a fall day six years after the end of the Civil War, two men began digging a shaft on a hill near Joplin Creek in southern Jasper County, Missouri. Lured to the location by stories of lead lying as shallow as the roots of the prairie grasses, the two men, Elliot Raines Moffett and John B. Sergeant struck figurative gold and from those first few spadefuls of dirt the city of Joplin was established, as well their riches.

A native Iowan, Moffett was forty-three years old when his prospecting brought him to Jasper County. He and Sergeant had initially setup in the area of Oronogo, then known as Minersville, and acquired a mining interest in the vicinity of land owned by John C. Cox, a Tennessean who had arrived in the area years earlier. The lead strike, forty feet down, quickly led Moffett and Sergeant to build the first lead smelting furnace north of present day Broadway and on the banks of Joplin Creek. The smelter was not the only “first” that Moffett and his partner brought to the mining camp and later the city. In 1873, when the cities of Joplin and Murphysburg joined together to form Joplin, Moffett was the first mayor. In addition to building stores in the fledgling camp, he and Sergeant also opened one of the first banks at 315 Main Street and founded the Joplin & Girard Railroad completed in 1876 to connect the growing lead furnaces of the city to the Kansas coal fields. A second railroad to Pittsburg, Kansas, was completed and celebrated on July 4, 1876 with a golden spike driven into the earth at the Joplin depot. Later, Moffett sold his interest in the railroad and its right-away southward to the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway, also known as the Frisco, for a hefty $350,000. Not long after, Sergeant and Moffett opened up the White Lead Works which later became known as the Picher Lead Works.

It was prospecting which brought Moffett to the Joplin area, it was also that which led him to leave for Northwest Arkansas. In the belief that more incredible lead veins were waiting to be discovered in Arkansas, he prospected the hills around Bear Mountain. He found some lead, but not enough to make a second fortune. Instead, Moffett purchased hundreds of acres of land and went into the business of fruits and grapes. It was as a shepherd of orchards that Moffett spent the last years of his life until he passed away in February, 1904, in Crystal Springs, Arkansas.

Upon his death, one Joplin newspaper wrote of him:

“The announcement of his death spread rapidly over the city yesterday evening and many sincere expressions of regret were voiced, and the utterances were of that sincere character that indicate true regret – the regret that is always felt at the demise of a truly good citizen. The reason of this is very apparent when it is known that he was instrumental in building the first schools and the first churches, and was a willing contributor to many movements for the city’s welfare.”

Proud to Visit Joplin’s Jail

In early Joplin, there was no shortage of Joplinites who were escorted to the city’s hoosegow. Surprisingly, some of these individuals were quite proud of their predicament. A Joplin Globe reporter interviewed Joplin Constable Arch McDonald about the phenomenon,

“You may not believe that it actually makes some people proud to be arrested. There’s all the difference in the world the way various people take the situation when the officer is compelled to duty. Some men readily appreciate the officer’s difficulties and prepare to go right along just like attending to any other business engagement; while others blame the officer who is called upon to serve the warrant and think its his fault, much the same as some people hold it against the postman when they fail to get a letter.”

Another Joplin police officer, Will Gibson, offered his own experience,

“Proud? Why yes, it’s the event of some fellows’ lives to get arrested, and some of them think it a real honor to be shown the distinction of being singled out of a crowd and marched down the street to jail. I arrested a young miner from Chitwood the other night for being drunk and disorderly on Main Street between Fourth and Fifth, and he didn’t seem half so drunk after I took hold of him. He wasn’t scared sober, either, but was just swelled up over having the strong arm of the law take notice of his antics, I guess. He braced up at once and told me that was all right, that he could walk straight, and then stepped off down Main street like a ham-strung thoroughbred, looking first to the right, then to the left, and making it a point to say something to every acquaintance he saw. He was plainly the cock of the walk.”

Deputy Sheriff Clarence Kier had this for the reporter,

“Nor are the drunks the only ones who feel the honor of being taken into custody. I’ve seen men arrested for some petty offenses of a more or less serious nature who got right chesty over it and swaggered down the street. One man in particular from over in East Joplin put the thing plainly when I started for the car line with him and his wife called to know where he was going. ‘Can’t you see,’ responded the fellow with a sort of self-important air,’ that I’m being arrested!”

Finally, United States Deputy Marshall, Henry Platt, offered his own experience,

“There’s another phase to the seeming willingness of some men to go along with the officer. I’ve seen federal prisoners puff all up when thrown into jail, and hold themselves aloof from common state felons and petty criminals, but that isn’t the secret of it. You’ll find that it isn’t only the novice nor the best citizen who goes along willingly with the officer, but that the very worst criminal of all is a good dissembler and very frequently scores a point by the apparent acquiescence and good nature with which he submits to arrest. The quiet man is often worse because he is shrewdest and most slippery of all evil doers.

He is not the murderer nor the criminal of passion, but the criminal of property, the thief, the forger, the embezzler, the counterfeiter, the one who works along original and stealthy lines. He’s just smart enough to know when he’s cornered, and if he sees that the chances for escape are all against him he quietly submits and goes along with the hope of affecting escape later, or by getting the minimum penalty by arousing the least suspicion. When the time comes for his break for liberty, the seemingly well behaved and tractable prisoner shows himself to be the most desperate of the bunch. He’s the criminal exemplification of the man with the ax to grind.”

An interesting aside to be picked up from the answer is the fact that Joplin police would use the trolley line to take prisoners back to the city jail. The equivalent today having a police officer get on a city bus with a prisoner in handcuffs.

History in the News: Historic Home in Joplin In Danger

This last weekend, the Joplin Globe published a story on the two story house on Schifferdecker Ave. The handsome house with a stone facade belongs to the late J.T. Goodman and his wife, Yvonne. The historic home, which likely dates to the early years of Joplin, was damaged by the May 2011 tornado. As seen in the above photograph, the home presently has no roof which is accelerating its danger of being declared condemned by the city. Joplin history expert and director of the Post Memorial Art Reference Library, Leslie Simpson, is presently trying to research the history of the home in an effort to help its preservation. So far, Simpson has discovered that it was on the property of Thomas Cunningham, one of Joplin’s wealthiest citizens at the turn of the century. Likewise, a mortgage deed indicates it might have even been built in 1873.

The historic home is currently before Joplin’s Building Board of Appeals. Unfortunately, due to the death of J.T. Goodman and a refusal by the Goodmans’ insurance company, the family has no funds to make the repairs needed to save the home. At the moment, Simpson is seeking to learn more of the home’s history which might translate to convincing the city Board of Appeals to spare the house more time to be repaired.

If you know anything about the house pictured above, located at 2725 S. Schifferdecker Avenue, please contact Leslie Simpson at the Post Memorial Library: (417) 782-7678. This is a piece of Joplin’s history, it needs to be saved!

A Fireman from Joplin’s Past

Today’s post is a glimpse at one of Joplin’s earliest firemen. As previously covered on Historic Joplin, the Joplin Fire Department came into existence in the mid-1870s. Below is an unidentified fireman of the era who helped protect the young city of Joplin from the dangerous threat of fire.