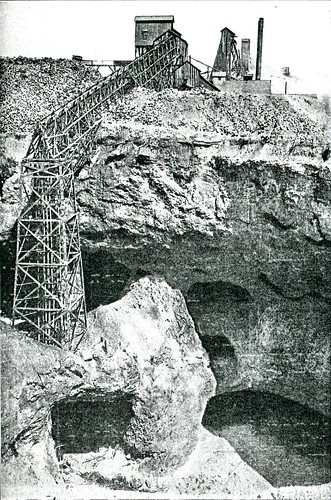

While the majority of Joplin’s lead and zinc mines were below ground, and in fact, much of Joplin is built above those shafts, there were some that were open to daylight. Below is a photograph of one of the best examples, the aptly named Daylight Mine.

The Curious Fate of Harry Roach

Harry Roach was a young Hoosier who traveled to the Tri-State Mining District to seek his fortune. He found employment with the superintendent of the Troup Mining Company located outside of Carterville. In 1892 Troup, along with two other men, were in the company’s Daisy Mine when the roof collapsed on top of them. The three men were beyond rescue and Harry Roach’s dreams died with him.

Three years later, the mine experienced a cave-in, and the remains of Harry Roach were discovered. Miners removed the remains and recovered $3.50 in silver from his clothing. A month later, miners working a drift in the Daisy Mine found several more of Roach’s belongings buried in the rubble. Among the items that were found were a gold pocket watch “in splendid condition” stopped at 2:20; a pocketbook with $45 and some still legible newspaper clippings in good condition; and part of a vest and a shirt. At the time Roach was killed, he was reportedly wearing a “very costly diamond ring” which was not located, as only part of his skeleton had thus been recovered. It was not until another month had passed that miners came across the bones of a foot in a “congress shoe,” a piece of collar bone, a shoulder blade, and two ribs.

Thus was the fate of Harry Roach.

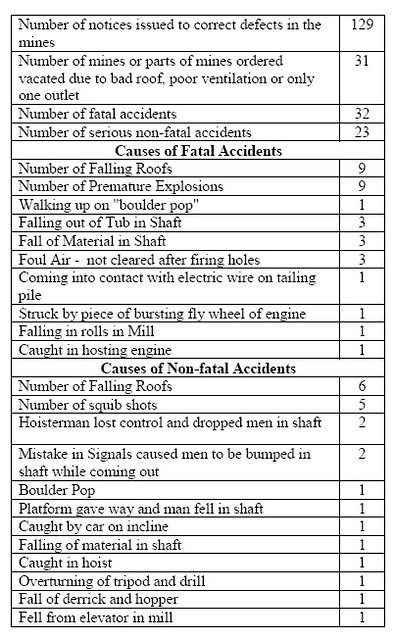

Perils of the Mines – Snapshot 1910

From the beginning, lead and zinc mining in the Joplin district was a dangerous means to make a living, and if lucky, a fortune, too. The year 1910 was considered a good one, respectively, when compared to 1909 when 51 miners lost their lives. In 1910, in contrast, only 32 miners were killed in the pursuit of the valuable ore. Every year, mine inspectors from the state toured the mines which surrounded Joplin to ensure compliance with mining laws and to note deaths and the causes behind them. In 1910, two inspectors toured 551 mines and 65 accidents. Here are the results and a snapshot of mining in Joplin in 1910.

In summary, the most dangerous element in a mine came from above. Of the combined deaths and serious injuries, falling mine roofs accounted for 27% of the victims. The next deadliest was the more obvious danger of explosives in the form of premature explosions, squib shot (involved in the dynamiting process), and to a degree, the foul air which was caused by failing to blow out the air in a mine following an explosion. Sadly, even entering and exiting a mine bore a certain amount of lethal danger, as our previous post on the unfortunate Number 52 noted.

Source: Joplin News Herald

Mining – Progress and Prosperity

An illustration from the Joplin Globe invoking the spirit of progress that pervaded much of Joplin’s history.

Source: Joplin Globe

The Reminiscences of G.O. Boucher — Part I

In the early months of 1910, a Globe reporter stopped by the home of G.O. Boucher at the corner of Joplin and Twentieth Streets to interview him about historic Joplin. Boucher gladly obliged him. Here at Historic Joplin our philosophy is to allow the voices of the past speak for themselves in their own words with as little interference as possible, even if we abhor the usage of some of the language used. For those sensitive to the use of racial slurs, it may be for the best to skip this entry as it does include some graphic language. What follows are Boucher’s recollections in his own words as they appeared in the Joplin Globe.

“I came from Mineralville in the spring of 1871 in company with John Sergeant, at that time a partner of E.R. Moffet. They were the first men to start the wheel rolling for the building of the present city of Joplin. Among the men who were interested in this undertaking were Pat Murphy and W.P. Davis who laid out the first forty acres in town lots, on which the largest and most valuable buildings of the city now stand.

The first air furnace built in the Joplin mining district was constructed by Moffet and Sergeant. T. Casady, a man from Wisconsin, handled the first pound of mineral which was smelted in this district in the mill erected by them. The smelter was located in the Kansas City Bottoms between East and West Joplin. A. Campbell, H. Campbell, A. McCollum, and myself were the first smelter employees in this district. The fuel used in the smelter was cordwood and dry fence rails, which were hauled from the surrounding country. The first men who handled rails and sold to the smelters were Warren Fine and Squire Coleman, the latter now living in Newton County.

The hotel accommodations at that time were poor and the first ‘beanery’ was a 24×16 foot shack erected by H. Campbell. His family occupied the house and they boarded the smelter crew. We found sleeping quarters wherever we could find room to pitch our tents. the boys would stretch their tents and then forage enough straw to make a bed and this was the only home known to them. E.R. Moffet and myself slept in the smelter shed on a pile of straw and for some time we slept in the furnace room on the same kind of bed. About the last of August of the same year Mr. Campbell erected what was then quite a building. It was two stories high, four rooms on the ground floor, and two above. This was at the southwest corner of Main and First Streets, now called Broadway. Just about this time Davis and Murphy began the erection of a store building just across the street from the hotel.

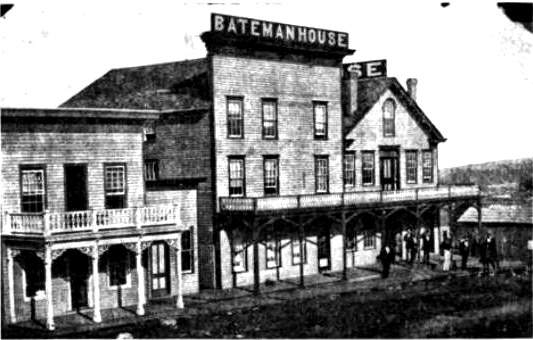

Another early hotel was the Bateman hotel, moved from Baxter, Kansas, to Joplin in 1872. It promptly burned down three years later.

Speaking of the first business building erected in Joplin, William Martin built a 16×16 box building on Main Street between First and Second Streets and put in about $125 worth of groceries and a small load of watermelons. Soon after this, a man known as ‘Big Nigger Lee’ established a grocery store on the opposite side of the street from Martin. He put in a larger stock but did not have as good a trade as Martin on account of having no watermelons. Some of the older residents remember ‘Big Nigger’ Lee as he was in business here for several years.”

More to come from the reminiscences of G.O. Boucher and in the future, Historic Joplin will address the issue of racism in Joplin to provide a clearer picture of how hatred affected the city’s African American citizens.

Source: Joplin Globe, “A History of Jasper County, Missouri, and Its People,” by Joel T. Livingston.