A former Joplin resident headed to Alaska during the great Klondike Rush of the 1890s. He wrote to relatives in Fairfield, Missouri, who shared the letter with the Joplin Globe:

“I will try to write you a few lines in answer to your letter I received this morning. I will have to ask you to excuse this dirty paper, for it is all I have, and paper is hard to get in this country. My partner and I landed in Dawson City yesterday in the best of health, but we are immediately worn out.

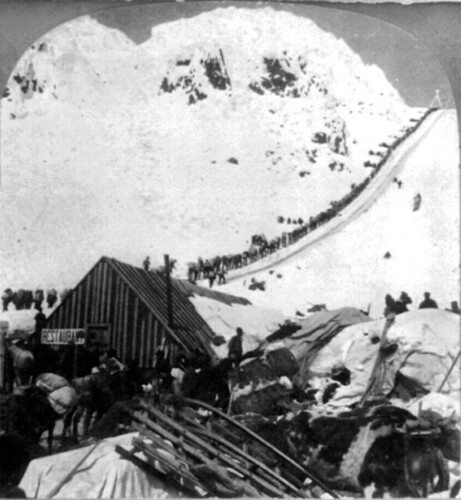

We had an awful trip, a trip that tried one both in strength and heart. First, it required one to have a strong constitution. To give you some idea of what we went through with, I will relate a part of our trip from Glenora to Dawson City via Teslin lake. First, it cost us $400 to get 500 pounds of provisions carried from Glenora to Teslin lake, a distance of 200 miles. We had to walk, for it was impossible to get a ride.

Even women tried to walk over but failed. We had to wade streams and mud up to our knees and sleep in wet blankets at night. It took us 21 days to make the trip to Teslin lake. There we had to build a row boat and start down the river and many times my partner wanted to turn back, but I told him no, that I was determined to go through or die in the attempt, for I had long ago learned that a faint heart could conquer nothing.

Now I will give you some idea of the suffering on that trail. There were 2400 persons left Glenora and only 230 out of that number ever reached Dawson City. Many turned back broken-hearted while many lost their lives. I don’t think I am very faint-hearted but I would not come in over that trail again for all the money in Alaska.

I have seen men sit down and cry like a child when they saw that they could not stand the trip and would have to turn back.

The scenery was the grandest I have ever seen but a man could not enjoy it.

I live to get home again. I will tell you more than I can write in a month, for I know I have taken the greatest trip of my life or at least I never want to take another one like it.

We thought we were picking the best trail but instead of that we got the worst one and had to make the best of it we could.

The ground here is covered with a coat of moss about a foot thick. Under that is ice and frozen dirt. There is no level ground here. It is all mountains. It is very rich in gold and we still think we will make our fortunes before next August. My partner is an expert miner but I rely on my own judgment. We are on a [word obscured] now for a lay in the mines. I have come here to make a stake and intend to make it. The output of the mines this spring was $22,000,000, the richest output in the history of the world.

Dawson City is a city of 20,000 people. Many are homesick and will go home, while many have no money or provisions and cannot get away, and it seems that starvation awaits them. To walk the streets of Dawson reminds one of being at a funeral. You never see a smile on anyone’s face. There are too many men here that were never away from home and they don’t know how to meet disappointments and hardships. There are lots of provisions in Dawson, but they are very high priced.

We have money and provisions enough to winter us nicely. Wages are $10 a day and board yourself. If a man is a good rustler he can make lots of money here. As this will probably be the first letter from Dawson this summer to reach your part of the outside world., I would like for you [to] tell the boys to think before they start, especially those who have never been away from home. I would not advise anyone to come to Alaska, neither would I advise them not to come. Everyone must come on his own responsibility.

I do not need nice clothes here now, for I look like the breaking up of a hard winter. Tell the young people of Fairfield that I wish them a pleasant autumn and happy winter.

I will try to get another letter out to you before the freeze comes. I send my love to you and all inquiring friends. I remain,

Yours, as ever,

Ed Ferguson.

Source: Joplin Globe