As the riches of the mining fields of Jasper County drew investors, miners, and speculators in the 1870s, the need for a banking institution was obvious. One of the first men to step into this void was one of the fathers of modern day Joplin, Patrick Murphy, originally of Carthage. He and an associate established the town of Murphysburg, which later merged to form Joplin in 1873, and two years later, Murphy opened the Banking House of Patrick Murphy. A two story brick building, it was located on Main Street between Second and Third Streets. Murphy’s endeavor was a success.

A sketch of Patrick Murphy in his prime.

Such was the success that the financial institution attracted investors and in 1877, the Banking House of Patrick Murphy was re-chartered and organized as the Miners Bank of Joplin. Murphy served as the first president of the bank, and was followed by Thomas E. Tootle. The first head cashier was Frank Kershaw. Kershaw’s successor was A.H. Waite. Most customers would have more likely known and recognized C.H. Spencer, who served as head cashier for at least sixteen years leading up to 1906. Local magnate Thomas Connor had served two terms as bank president. In fact, the board of directors included many of the wealthier citizens of the city, such as Connor, Howard C. Murphy, Edward Zelleken, C.W. Glover, and H.O. Bartlett.

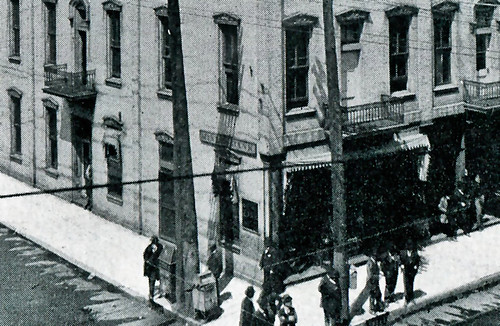

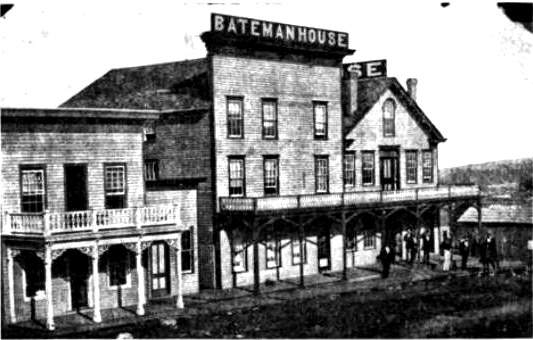

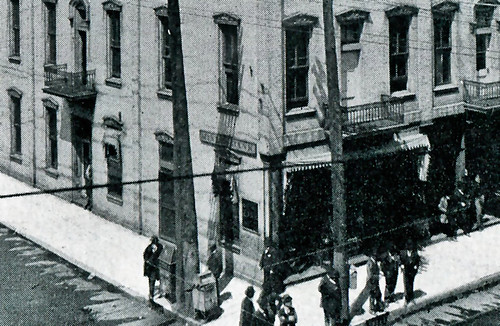

Magnified here is the corner of the Joplin Hotel, displaying the Miners Bank sign.

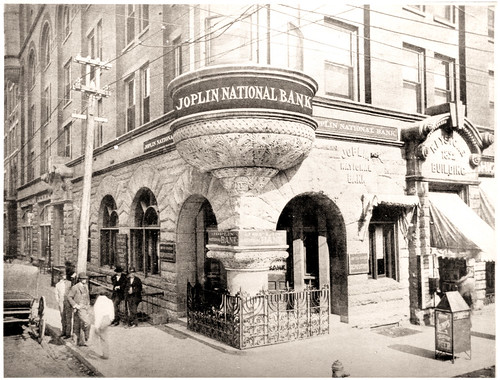

Miners Bank’s success was also reflected in its financial holdings. At its inception the bank held $25,000, by 1890 this was increased to $50,000 and a year later doubled to $100,000. Due to growth of its assets and the increasing number of depositors, Miners Bank moved from its location between Second and Third to take up residence to offices in the Joplin Hotel, and there remained from about 1885 to 1905. Over a slightly longer period of time than its stay at the Joplin Hotel, reported deposits at the bank grew from $35,700 to $949,000. Loans increased from $6,500 to $425,000. Cash on hand went from $15,000 to a bank robber’s dream of $97,000. Figures from 1905 listed the six most successful banks by deposits, and the Miners Bank was first and foremost, besting its nearest competition by more than $55,000. Until the bank’s move in 1905 from the Joplin Hotel, its chief competitor and runner up in the 1905 figures was the Joplin National Bank, located just across the intersection situated on the bottom floor of the Keystone Hotel.

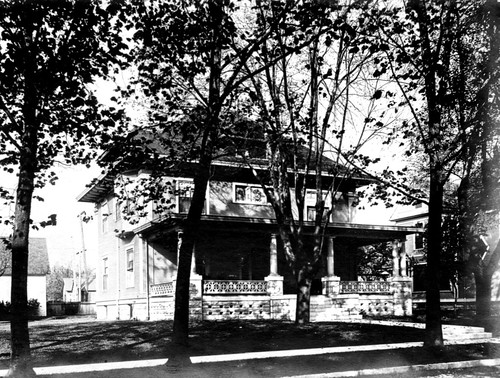

The Miners Bank building as featured in an article announcing its opening.

The move in 1905 may have been prompted by the plans of Thomas Connor to raze the three story Joplin Hotel with plans to build a larger, grander establishment, or may simply have been due to the banking institution’s success. The bank’s new home was just a block away from Main Street, where Fourth Street intersected with Joplin Street. The new building was described by one of Joplin’s paper as a “beautiful modern building, with elevators and all modern conveniences.” The offices were equally beautiful and constructed of marble, tile and steel. Designed by August Michaelis, one of Joplin’s most prolific and talented architects, the building was designed to accommodate an additional four more stories should the need arise. It was built at a cost of $125,000 by the firm of C.A. Dieter who later oversaw the construction the Connor Hotel.

Another photograph of Miners Bank not long after it opened.

From July 1st of 1905, Miners Bank inhabited the ground floor, leaving the upper floors open to paying tenants, architect Michaelis included, and remained there until 1930 when it merged with Conqueror First National Bank. After the merger, the bank moved back to Main Street for the first time in twenty-five years, and with its departure ended an illustrious history that began in 1877. The last home of Miners Bank remained in use until a disastrous fire prompted its demolition in 1982.

The Miners Bank building a few years after its opening.

A view of the Miners Bank building in context at the intersection of Fourth and Joplin Streets.

Sources: Missouri Digital History, Joplin News Herald, and the Story of Joplin by Dolph Shaner.