Over the years, Joplin was home to many newspapers: The Advance, the Evening Times, the Free Press, the Globe, the News-Herald, the Labor Record, the Missouri Trade Unionist, the Morning Tribune, the Daily News, the Southwestern, and the State Line-Herald. These are just the ones that survived for posterity. There were other papers published in Joplin that, due to neglect, the ravages of time, and lack of interest, did not survive. Editors and owners may have thrown the bound volumes in the rubbish bin, fires may have destroyed them, or they simply crumbled away over time, printed on poor quality paper. There are, for example, no known surviving copies of the Joplin American, the paper that Thomas Hart Benton worked for when he lived in Joplin. There were also many local papers, such as the intriguingly named Carterville Rocket, that did not survive, either.

Of the papers that did survive and are captured for all time on microfilm, only one Joplin paper represented the interests of the city’s African-American population, the Joplin Advance. The Kansas State Historical Society collected and preserved the sole surviving issue of the Advance, allowing us a very limited look at the sole African-American newspaper in Joplin.

The first issue of the Joplin Advance was published on Friday, May 10, 1895. It was four pages in length. The first page bore the following greeting:

“Salutatory:

We have come among you to stay and assume a part of the responsibilities of the citizens of Joplin and vicinity. We will say that we have to profess to make except to do all the good we can and the least harm possible, advocate nothing but [missing word] Republican principles, for the promotion of the general welfare of the Negro race and his friends.

In order for the colored people of Joplin and the surrounding towns to maintain and keep the ADVANCE from going to the walls, it is necessary for them to read every advertisement of the merchants very carefully and patronize only those. The fact is, that no business man wants to advertise in any paper unless he expects to be benefited thereby. The advertisements [sic] is the back bone of a newspaper and, unless a merchant is benefited by advertising in a colored paper, as a matter of fact, he will not advertise. We regret to say, that our people cannot afford to maintain their press, and if we expect to have a newspaper in our midst, we must patronize the merchants who advertise in, and extend a friendly hand to our enterprizes [sic].

In looking over the broad field in this county with an eye singular to the prosperity of our people, we can see a great chance for an improvement, political, socially, and otherwise, and we firmly believe that, if we can bring about the state of things by the publication of a first class patriotic Negro newspaper, dedicated to the purpose of bringing the two races closer together, linking the Negro race in a better union, concentrate our forces, morally, socially, politically, intellectually, and otherwise, we will accomplish a great good, especially among the more ignorant whites as well as the blacks, if they will only read our paper.

W.L. Yancey.”

The rest of the paper was what we would consider today to be AP wire reports, save for one page which mentioned local events, and had a few paid ads for Joplin businesses such as Mack the Tailor, Jones Confectionary, and the Golden Eagle Clothing House. Notably, the ad for Jones Confectionary stated, “Dealer in Candies, all kinds of Fruit, Nuts, and Soft Drinks. It is the only place where colored people can be accommodated to an Ice Cream Parlor. 519 Main Street.” [Emphasis added]

African-Americans in Joplin could find out when services were being held at the M.E. church, the A.M.E. church, and St. John’s Baptist church. Those interested in fraternal organizations could find meeting information for the Masonic Myrtle Lodge No. 149, the Guiding Star Court, and the Knights of Pythias Lodge No. 11.

Most importantly, though, due to segregation, blacks were often at a loss with regard to knowing which businesses they could and could not patronize. The Advance pointed out which businesses catered to African-American clientele, and although we cannot be sure, would surmise that most of the businesses they recommended were owned by fellow African-Americans.

James Mason, driver of general job wagon no. 57, was recommended for one’s moving and delivery needs and one could visit any of three barber shops for a shave: the I.X.L. Shaving Parlor [516 Main Street], the Imperial Shaving Parlor [320 Main Street], and G.W. Potter’s [106 Main Street]. Laundresses Miss Mary Edwards [First Street], Mrs. Graton [620 Joplin Street] Miss Eva Door specialized in laundried collars, cuffs, and shirts. Should you want a new dress, Mrs. Brisco McLerore could be found at 120 Pearl Street. For boarding, Mrs. Lou Barnett offered lodging on Seventh Street “between Kentucky on Penn. Ave.”

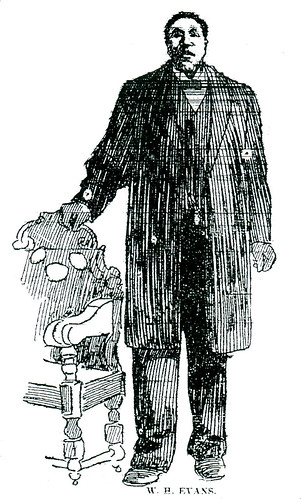

The man behind the paper was African-American W.L. Yancey. In addition to being the editor and owner of the Advance, he was also an attorney. In his first “salutatory” message to readers, Yancey asked his fellow African-Americans to support the paper, lest it fail. He knew that whites would not subscribe to his paper; instead, they would read the “white” papers in Joplin. He also knew that advertising was crucial to the newspaper’s success. But advertising in a black newspaper, particularly for white businesses in a city with a small black community, was not advantageous or attractive. Even neighboring Springfield, with a sizable black population, could not sustain its own African-American newspaper.

Curiously, the 1895 Kansas State census lists William L. Yancey and his wife Clara as living in Pittsburg, Kansas. The census itself was taken in March, 1895, just two months before the Advance was first published. It also explains why there is a small smattering of Pittsburg, Kansas, news on the front page. Yancey may have been trying to bridge the gap between the black communities in Joplin and Pittsburg with his paper. He listed his occupation as “newspaperman” while wife Clara was a “housekeeper.” They lived in the midst of white families.

The 1900 Federal census tells us that William L. Yancey lived in Joplin [south of Broadway on Central Avenue] at that time. His occupation was listed as attorney and his wife, Clara, had “printer” as her occupation. Were they still publishing the Advance? Or did Clara just work as a printer? Because only one single issue of the Advance survived, we cannot be sure how long the paper lasted. If you check the city directory, however, Yancey is not listed which shows that one must always check every source available. Still, we are left with questions: Where did Yancey attend law school? There were African-American lawyers in Springfield who attended Howard University. Did Yancey go to Howard? Why did he move to Joplin?

Yancey did not remain in Joplin. Perhaps frustrated by the lack of opportunity, he moved on, and eventually divorced Clara. She later died in 1963 in Michigan.

Sometimes searching the census can be a challenge, as with Yancey and the 1910 census. He may or may not appear in the 1910 Federal census for Yakima, Washington. If it is him, the census taker wrote down the wrong middle initial and identified him as a “white” “lawyer.” Yancey was listed in previous censuses as either black or mulatto. Is it possible he tried to pass for white? Or is he just hiding out in the census and this is a different William Yancey? Census takers could and would make mistakes.

At any rate, we do know that by 1920, he appears to have remarried, and settled in Yakima, Washington. Fifty-one years old, both Yancey and his wife were working as “janitors” in a “business building.” In 1930, he is missing from the census, but his wife Hannah is listed as divorced. Yancey may have passed away, or may have simply eluded the census taker where he lived.

His story is illustrative of the challenges African-Americans faced in American society in the time between Reconstruction and the Civil Rights movement. Yancey, once an attorney and newspaper editor, spent his later years working as a janitor. Were it not for the Kansas State Historical Society preserving the single surviving issue of his paper, we would have never known his story, nor the fact that once upon a time Joplin had its own African-American newspaper.

If you ever come across an old Missouri newspaper, you may want to call the State Historical Society in Columbia and ask if they have it. If not, by allowing them to microfilm the paper, you could help preserve Missouri’s history. Who knows — maybe someone has a copy of the Joplin American featuring one of Thomas Hart Benton’s cartoons waiting to be found!

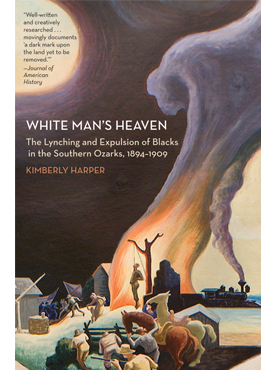

It’s been awhile, but it seems only natural to recommend a good book to help us understand these turbulent times. If you have not read it,”White Man‘s Heaven: The Lynching and Expulsion of Blacks in the Southern Ozarks, 1894-1909″ by Kimberly Harper explores the complex racial dynamics of the early twentieth century Ozarks. If you are like us, you might have grown up in Southwest Missouri during a time when there were few, if any, people of color in your community and wondered why. Well, this is why. One reader called it the Ozarks version of “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

It’s been awhile, but it seems only natural to recommend a good book to help us understand these turbulent times. If you have not read it,”White Man‘s Heaven: The Lynching and Expulsion of Blacks in the Southern Ozarks, 1894-1909″ by Kimberly Harper explores the complex racial dynamics of the early twentieth century Ozarks. If you are like us, you might have grown up in Southwest Missouri during a time when there were few, if any, people of color in your community and wondered why. Well, this is why. One reader called it the Ozarks version of “To Kill a Mockingbird.”