Over the years Joplin saw its share of curiosities. In her book, Tales from Joplin, Evelyn Milligan Jones recounted the story of the “Man Horse.” According to Jones, the Man Horse was an individual who believed he was a horse and could often be seen “charging down the street pulling his own buggy. He had his boots shod with horseshoes, and sometimes ate hay from the back of his wagon, or grass at the roadside.”

Just as a real horse would, the Man Horse would “shy at a blowing piece of paper and run wild for a few blocks.” Regrettably, Jones has little else to say about Man Horse, nor did she divulge his real name. Man Horse was only one of a handful of characters to roam the streets of Joplin.

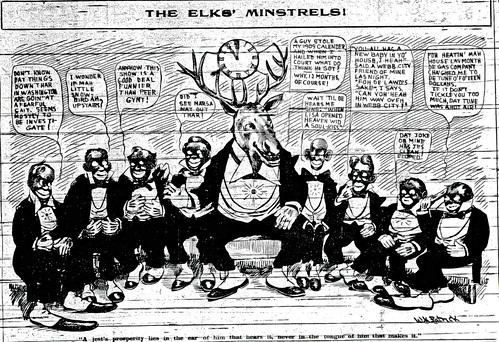

Another colorful character that Jones recounted was “Nigger” Evans. Joplin composer Percy Weinrich remembered him as the “big man who used to roam the alleys and byways of Joplin in his trash wagon.” Mothers would tell their children, “If you don’t behave, Nigger Evans will get you!” Evans inspired such fear that the Joplin Elks “dressed him up in a leopard suit, and provided him with a whole haunch of meat which he flourished like a club, pausing only to gnaw at the raw meat now and then as he marched along. Children who saw this had wilder nightmares than TV can inspire.”

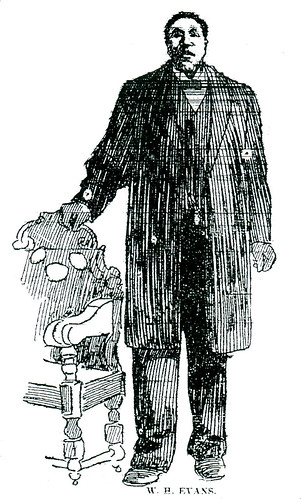

But there was more to “Nigger” Evans than just a crude racial caricature. His real name was W.H. Evans and he made his living in Joplin as a “city scavenger.” As he made his way through the streets of Joplin, Evans stood out due to his extreme size: He was six feet eight inches tall, weighed 350 pounds, and wore a size 15 shoe.

A native of Cairo, Illinois, Evans was born to slave parents. According to Evans, his father “stole his mother from Alabama and then ran off to sea.” As soon as he was grown, Evans joined the Ninth United States Cavalry, where he served for five years. He later worked as a railroad brakeman in Texas. It was during this time in his life that he killed a fellow African American with his fists, ending his ambition to become a prizefighter. Despite his past, Evans found employment with the Barnum and Wallace circuses as “Hi-Ki the Wild Man.”

Barnum circus barkers would cry out to curious crowds:

“Hi-Ki, the flesh-eating wild man. Species of Cuban negro. Captured forty-two miles south of Manila by a group of American soldiers. Cannot understand a word of English. The only one in captivity.” For those brave enough to view “Hi-Ki” they entered a tent and saw Evans seated in a cage chewing on a piece of raw beefsteak handed to him through the bars with a pitchfork.

When asked about his days in the circus, Evans opined, “Barnum was a little off when he said the American people like to be humbugged. It is not because they want to be humbugged that makes them pay out their money, but it is their desire to learn and see something they never saw before. The American people ain’t afraid to invest in anything if it’s new.”

After he left the circus, Evans settled in Joplin where he owned “several thousand dollars’ worth of property besides a farm of 120 acres in Texas and town lots in Palestine and Bremond.” In Joplin he was known as a “wonder of the people of his home town and the ‘bogy-man’ of the little children.”

Evans was enough of a local fixture in Joplin that in 1896, his name was put before the Republican county convention as candidate for coroner, but his name was withdrawn from voting, and he left the convention hall in disgust.

Evans claimed, “They hadn’t more’n got half way through voting when some Republican gets up and says that if they elect me as coroner and the sheriff dies, they’d have a nigger sheriff. Then he went on and talked about what he called ‘wisdom.’ and then they quit voting. Then I told them what I thought about the Republicans. There wasn’t no money in the job then anyway, just empty honors.” Evans later joined the Democratic Party.

He explained to a reporter, “If old Abraham Lincoln could come back to this country again he would say the same thing about the Republicans and would run them all out. The Republicans just use the negro as a tool to be held up and hammered and they are doing the negroes in the south more harm now than anybody else by arraying them against the best friends they’ve got down there. No, sir, I’m a Democrat, and I expect to help fight for the Democrats, even if I did go down to defeat twice with [William Jennings] Bryan.”

Evans believed “everybody ought to take part in politics. If a man is honest and his character unimpeached, he should have consideration. But it’s all a manipulating scheme, and the feller that gets elected goes off with the cream.”

At the time Evans made his statement, Democrats were considered the party of “wets,” which is to say those who were against prohibition. Curiously he declared:

“But some of these white folks around here ain’t much fitting to govern themselves. I has always been an anti-prohibitionist, though I never drank nor used tobacco, except I drank a little whisky for medicinal purposes but that don’t do much good. But I’m going to vote for the prohibitionists this time. The other night I saw thirty-six men with buckets over their shoulders drinking beer in a saloon at one time. Then they do something and blame the other feller for it. Whisky in, wit out. I wouldn’t say a word if they was the only ones hurt, but more of them fellers had wives and children at home. Yes, I’m going to vote for the prohibitionists this year.”

For a man who wore a leopard suit, Evans viewed the world with a far more serious perspective than many whites may have assumed and refused to acquiesce to the image of a mere wild man.