Seven years after the successful lynching of Thomas Gilyard, a topic we will be giving considerable attention to in the near future, another lynching almost occurred in the neighboring community of Galena, Kansas, literally down the road from Joplin.

The would be victim of mob violence was an African-American resident, William Boston, or William Baldridge (as he was also sometimes called), had only recently been released from the state reformatory for cutting a street car conductor. As of 1910, Boston was just 21 years old, could not read or write, and may have even been listed as “deaf and dumb,” in the census. He was a Kansas native, but lived with his widowed grandmother, originally from South Carolina. The job William landed was at the Windle & Burr livery stable, and with it the coworker, Benjamin Jones, a foreman, born near Kansas City and approximately 51 years old. The alleged events thereafter followed. It came to Boston’s attention that Jones had a considerable amount of money upon him. The not quite reformed liveryman waited until night fall and for the foreman to fall asleep. To ensure a quick escape, he walked to another livery stable and telephoned for a carriage to wait him at the east side of town, his destination the depot of the Frisco Railroad.

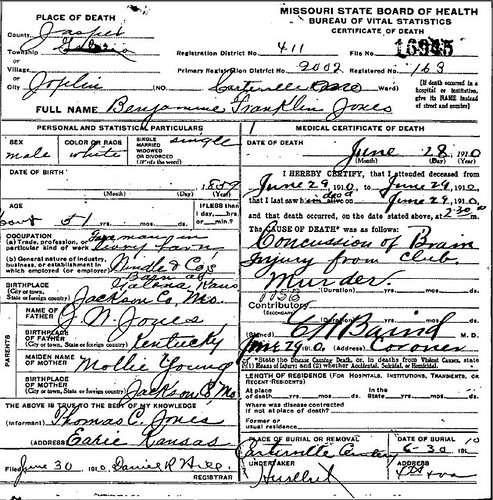

At that point, Boston returned to work and to the sleeping Jones. At this point, Jones had only hours to live, and of those hours, most of them spent dying at St. John’s Hospital. A piece of wood in hand, described as a scantling, Boston clubbed Jones in the head, smashing his skull. The killer took the money that Jones possessed and made for his escape. Not long after, the dying Jones was discovered by a coworker and the police alerted. It became a chase to catch the killer.

How the Galena police discerned that Boston would make for the train depot is unsaid, but there they found him with a believed intent to catch an eastward headed train. At the point of three revolver barrels, Boston confessed to his identity in the early hours of the morning. He was quickly taken into custody to the city jail of Galena, where to initial dismay, only $6 was found on his person. The lack of the estimated sum taken from Jones was a mystery soon solved by the inquiry toward the “chewing tobacco” that Boston had in his mouth. Forced to disgorge it, the tobacco proved to be $70. To the Galena police, as well the natives of Galena, it seemed for certain that Boston was Jones’ attacker. This was cemented by a supposed confession by Boston, locked behind the bars, that he was the only man involved and did attack Jones.

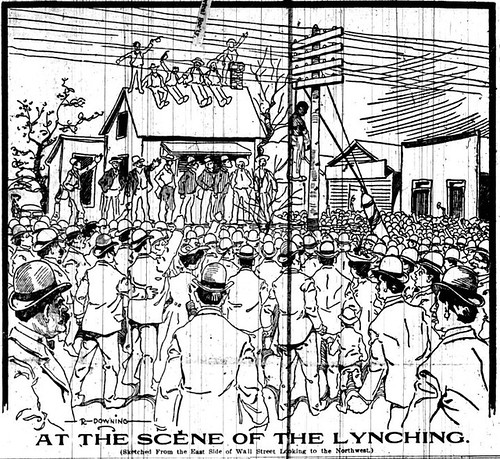

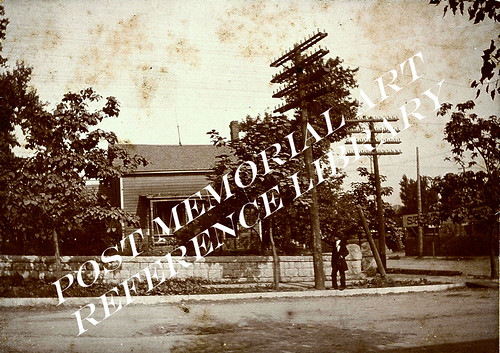

By sunrise, word has spread amongst the community of the attack and that the killer was in custody. Men, and later boys, began to gather around the jail. Hundreds, it was claimed, but by around 9 am, the number was said to be approximately 200. “Summary justice” for Boston was the subject of nearly every conversation, but, as a reporter noted, there seemed no leader ready to guide the mob into action. However, as time passed, the aggression of the mob began to rise. Galena police officers were “hooted and hissed,” as they began to repeatedly refuse to turn over the keys to the jail within which Boston sat.

The Galena police chief, John Fitzgerald, the 44 year old son of Irish immigrants, grew alarmed as the intensity of the mob increased. The police chief vowed not to allow his prisoner to fall into the hands of the ever more bold crowd and quickly made two orders. First, he stationed a number of officers at the front of the city jail, and told them to act as if nervous about protecting the prisoner inside. Second, he requested a car brought to the rear of the jail. The plan worked. As the mob watched the distraction out front, Fitzgerald with a handcuffed Boston climbed into the motorcar and swiftly sped away to the county jail at Columbus. It was no time sooner, that a blood thirsty leader finally emerged and an organized the mob prepared to force their way into the jail, but only like a wave breaking upon the shore, to disperse upon the news that their prey had gotten away.

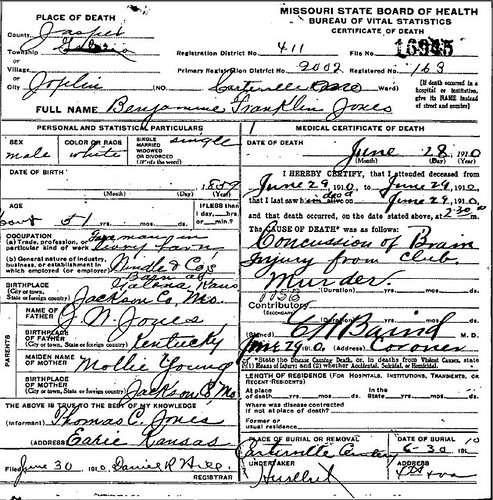

In a room at St. John’s hospital, Benjamin Jones, first generation American died of his wounds at approximately 2:30 pm on June 29, 1910. In Columbus, Kansas, William Boston quietly awaited to be tried. In Galena, Kansas, the Tri-State area narrowly avoided its next lynching following that in 1906 of Springfield, and the 1903 lynching in Joplin. Were it not for the quick thinking of its chief of Police, John Fitzgerald, the murderous legacy might have continued. For more on that legacy, either stay tuned in the near future for our posts on the 1903 Joplin lynching, or pick up a copy of White Man’s Heaven: The Lynching and Expulsion of Blacks in the Southern Ozarks, by Kimberly Harper.

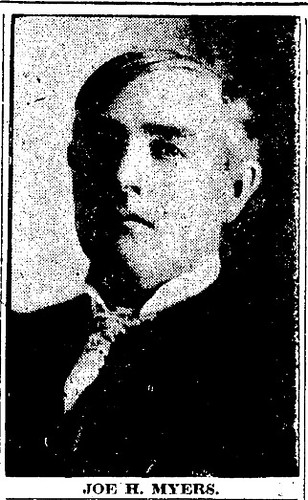

Death certificate for Benjamin F. Jones

Source: 1910 United States Federal Census, Missouri Digital Heritage: Death Records, Joplin Daily Globe