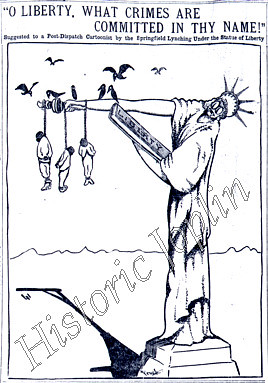

Editorial Cartoon from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, as a statue of freedom was placed at the top of Gottfried Tower where the three men were lynched.

One hundred and five years ago, on the night before Easter, a mob in Springfield, Missouri broke into the Greene County jail, carried three prisoners to the city square, and lynched them for the alleged assault of a white woman. The murder of the three men quickly became known as the “Easter Offering.” The lynchings made the front page of newspapers across the nation and faded only with news of a terrible earthquake which leveled the west coast city of San Francisco. Below is an excerpt from Kimberly Harper’s White Man’s Heaven, which in addition to covering the Joplin lynching of Thomas Gilyard, tells the story of the Easter Offering.

The following takes place after two men had already been lynched, Horace Duncan and Fred Coker.

“Resistance was nonexistent at the jail. Sheriff Horner and his men, absent since Duncan and Coker were seized, were nowhere to be found. Members of the mob strolled through the door of the jail unopposed. Men, armed with hammers, chisels, and other tools, walked through holding cells looking for Bus Cain and Will Allen. Bus Cain, however, was nowhere to be found. Apparently his cell was damaged during the first assault on the jail and Cain was able to slip away without being noticed. Cain, in his eagerness to escape, left Will Allen behind. When Cain’s absence was discovered by the mob, a litany of curses filled the air. Infuriated by his escape, men began to shout, “Take any negro and hang him!”

Allen, trapped in his cell, watched from his cot as a rough assortment of men began to coolly and methodically remove the lock from the cell door. Despite the cool night air, the men were drenched in sweat from their exertion. As men tired, they were relieved by fresh replacements. After almost two hours, sledgehammers were brought forth, and men began to steadily pound at the cell door with as much force as they could muster in the middle of the night. Just before two o’clock in the morning, the door to the cell was torn open, leaving nothing between Allen and his attackers. The emptiness between the men was momentary, as the mob rushed forward and seized the man who had been tortured by hours of violent screams and the prospect of the inevitable fate that awaited him.

Allen was blinded as a lantern was shoved in his face, as the mob, with a skewed sense of justice, sought to ensure they had the right man. Unwilling to meekly accept his fate, the 5’5” tall Allen wrested himself free from the hands of his attackers, and seized a nearby wooden club. He ferociously lashed out at the men around him, but “blows rained on his face and body like hail from a score of arms, and he was quickly subdued.” Allen’s bold attempt to defend himself enraged the mob. While curses and clubs flew freely at Allen’s obstinance, his hands were jerked forward and tightly bound together before he was dragged out of the jail. Once outside the jail’s battered brick walls, Allen insisted on walking, rather than be carried by the mob.

Screams and yells eerily echoed through the air as men fired their pistols in anticipation of a third lynching. In the midst of the chaos, Will Allen walked steadily forward with his head held high, determined not to show fear. The mob guided Allen toward the campus of Drury College where only months before he, together with Bus Cain, allegedly murdered O. P. Ruark. Hoarse voices cried out, “Hang him where he killed old man Ruark!”

Several Drury students who were in the crowd, fearful that a lynching on Drury’s campus would sully the college’s reputation, hurriedly held an impromptu meeting. It was decided that they would try to head off the mob and quickly spread out through the crowd yelling, “Take him to the square! Hang him with the other two! Take him back so the others can see!” The plan worked as the mob suddenly shifted direction and with one voice bellowed, “To the square!”

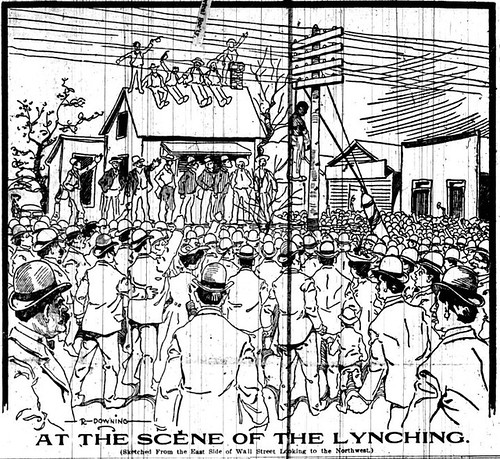

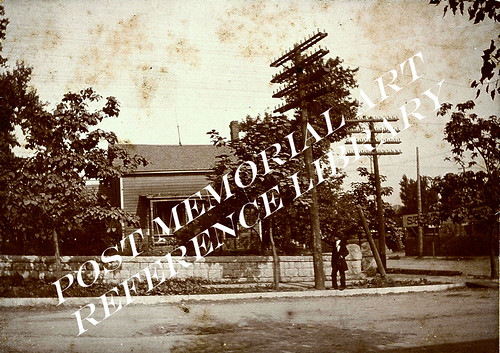

The city square with Gottfried tower in the forefront. Note the Statue of Freedom at the top of the tower. Beneath her, Will Allen, Horace Duncan and Fred Coker were lynched.

As the mob streamed toward the scene of Coker’s and Duncan’s grisly end, “Men talked to themselves and each other, swore fluently at nothing at all, and shouted all sorts of bloodcurdling things into the air without regard of their significance. Grown men shrieked and howled like demons, shouting to the leaders to hang the negro, to burn him.” It was on the corner of the square, as the howling processional began to arrive that Hollet H. Snow spotted Chief John McNutt and Officers John Wimberly, Henry Waddle, A. R. Sampey, E. T. W. Trantham, and Martin Keener, “laughing and talking and making no effort to stop the mob.” As Allen and the mob approached the square, it was shrouded in darkness, save for the harsh light that came from the bonfire built over the bodies of Fred Coker and Horace Duncan.

As Gottfried Tower loomed before him, Allen trembled almost imperceptibly, but regained his composure. He walked unaided up the steps that led to the tower’s bandstand. In front of Allen was a sea of faces, dimly illuminated by the flames of the bonfire, tense with anticipation. Those who stood on the fringes of the mob were shrouded in darkness. Allen, as he stood on the tower’s bandstand, may have recognized familiar faces. If he did, he did not cry out for help. Instead, he stood silently as an unknown man shoved a lantern into his face for those below, which caused the mob to call out, “Hang him!”

The man motioned for silence and then spoke, “Ladies and gentle – men, here before you is Will Allen, the man who cruelly murdered old man Ruark on the corner of Benton Avenue and Center Street. What will you do with him?” Over a thousand voices thundered in unison, “HANG HIM!” The man turned to Allen and asked, “Are you Will Allen?” Allen replied, “I am.” The unknown man then asked Allen if he had anything to say. Allen looked out at the crowd, straightened, and said, “Only that I did not kill Ruark.” Several men from the crowd howled, “Make him tell who did!” Allen, his hands still bound, declared, “Bus Cain killed Ruark. I had nothing to do with it.” The mob, unsatisfied with his answer, roared, “HANG HIM!”

Source: Reprinted with permission from the author, White Man’s Heaven: The Lynching and Expulsion of Blacks in the Southern Ozarks by Kimberly Harper.