Fifty Days of Sunday:

The Fireworks Begin

The dedication of the Sunday tabernacle began with five hundred strong choir voices shaking the rafters of the structure with “Wake the Song” and “Crown Him King of Kings.” On Sunday night, November 21st, the tabernacle was filled with six thousand “earnest, enthusiastic listeners,” who were eager to touch upon the excitement of the impending revival. After an invocation by Rev. J.R. Blunt of the South Joplin Christian church, and a few other introductory speakers, the guest-speaker of the night, Judge H.E. Burgess, of Aledo, Illinois, took to the podium that stood before the vast assemblage with the choir to his back.

Judge Burgess addressed the Joplinites as a man redeemed by a previous Sunday Revival four years earlier and rose to speak to them of what to expect from imminent arrival of the Reverend Sunday. He began with a tantalizing disclaimer, “I will attempt to tell you something of Mr. Sunday and his wonderful meetings. But it is impossible ever to attempt describing a real Sunday meeting. The only way such a meeting can be comprehended is for it to be seen…”

Burgess described the opinion of the evangelist by the citizens of Aledo, prior to Sunday’s arrival. They had “the same idea of Mr. Sunday – that those of any other city had — ideas merely gotten from rumor and hearsay that Mr. Sunday was simply an erratic grafter, who had discovered his wonderful gift of eloquence and personal magnetism, and was using this gift in a religious way merely because of the money he might thus gain.” It was an idea that was likely shared in Joplin by those less eager for Sunday’s presence, and a skepticism that had originally painted others like Burgess in Aledo. But, Aledo stated that as Sunday began to preach and he witnessed the effect on others, “…we unregenerated people began to sit up and notice.” For the power that Burgess ascribed to Sunday was one of indifference to appearance of proper church membership and an unflinching readiness to call out anyone that “a sinner is a sinner, no matter what kind of a front” the individual might put up.

Rev. Billy Sunday

The challenge that hypocrites would be spotlighted by Sunday undoubtedly was an exciting one for those who believed themselves immune and a nerve wracking one for those who feared public humiliation at the hands of the Evangelist. However, a desire to call out hypocrites was not limited to Sunday nor reserved for his arrival. The Democratic newspaper, the Joplin Daily Globe, opted to beat Reverend Sunday to the punch with a front page column in its morning edition, published the day of Sunday’s expected arrival, which repeated the findings of a Grand Jury on the recent crackdown of prostitution. The report stated that contrary to published reports, the crackdown that netted two madams and their ‘sinful sirens’ had been the order of the police judge, Fred W. Kelsey, not Mayor Guy Humes, and in fact the arrest had “astonished the mayor, chief of police, city attorney and other city officials…” The report concluded that prior to the arrests and thereafter [Editor’s emphasis] that “..bawdy houses, have been, and are now, running wide open to the public.” Finally, the Globe alleged that the same women were now hidden away in the countryside by the actions of the Republican city officials, as part of an attempt to create an appearance of cutting down on crime. Of note, the Grand Jury Report declared it had found no appearance of an agreement or contract between the city officials and the criminal offenders.

At the same time as the Globe pointed fingers at Mayor Humes, police chief John A. McManamy continued the civic crusade against crime with a crackdown on turkey raffles (the day before Thanksgiving). Described as a dice involved ‘wheel and paddle’ method to turkey distribution, and a corruption of a more charitable means of giving, the police chief declared that the turkey raffle was too close to real gambling for his liking. As a result, the fowl affair was shut down. It was only a few hours later in the afternoon, when a train pulled into Joplin and the Reverend Billy Sunday disembarked.

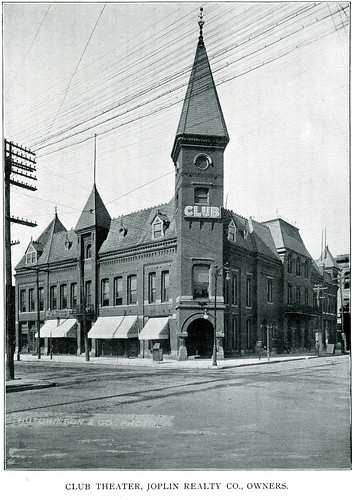

Around 6:30 pm, the excited crowds filled the tabernacle located on Virginia Avenue between Fifth and Sixth Streets and took whatever seats they found open and not reserved. The reserved sections were set aside for boys and girls, families of the ushers, and the deaf and hard of hearing. In addition, a telephone-like apparatus was setup with a microphone by the podium to handsets in the back, for those who failed to reach the hard of hearing section to hold to their ears.

“Billy Sunday Starts Fireworks…” was the headline the next day of Sunday’s first sermon. True to the words of Judge Burgess, the papers offered little to describe how the reverend began his sermon, instead relying on his words to convey the explosion of fervor and energy that the former ball player brought to the stage in front of likely more than 6,000 spectators. What was noted was that Sunday was “small and wiry and as active as a cat. He is constantly on the move and his every gesture indicates the vast reserve endurance which has helped to make him conspicuous…” Additionally, Sunday, was described as being, “…no bigger than the proverbial cake of soap after a hards day’s washing…” Sunday, as he began, “…dramatically hooked his clinched fist through the ozone and declared he was in position to defend himself and his policies.” Like Mayor Humes, against whom the paper compared Sunday, Sunday was a fast talker who said, “…as much in an hour as would an ordinary speaker in two hours.” Before he began in earnest, Sunday admonished the young people to silence, requested that mothers leave their newborns with caretakers by the doors, and then started his challenge to the people of Joplin. “There are liars everywhere…and no doubt there are plenty of them here.”

Sunday launched into a session of brutal honesty, at least from his perspective, “You must remember we did not beg the privilege of coming to Joplin; we were sought. We turned down one hundred other cities in order to come here. I presume I will say a whole lot that you won’t like. I’m not like the local ministers. They couldn’t be like me. If they said some of the things I will they wouldn’t hold their jobs three weeks.” The reverend then explained his plans, “My aim is to create a kind of evangelism that will reform drunkards and prostitutes; to restore happiness to the homes. Those who have friends they want to see led away from hell will give me their support. Those who don’t care where they or their friends go or what they do are opposed to me.”

The reverend also addressed the issue of collections. “In one day a circus will take $20,000 out of the city and it won’t leave one incentive for anyone to lead a better life. We surely ought to be able to get one-third as much in three weeks as the circus does in one day. God’s hardest job is to convert a stingy man.” The money, Sunday explained, went purely to the operation of the meeting and saving souls.

More to the point, Sunday fearlessly scolded the crowd, “We need more people right with God, in almost every church there are two classes; the ruts and the anti-ruts. A revival comes naturally in its proper place. A revival of religious interest is a necessity. It is a predominance of the material over the spiritual that is facing us. This is the busy age; It is the age of ‘isms and ‘cisms; there is more today to turn people away from God than ever before. When I see the street loafer standing on the corner discussing the greatest questions of the day and propounding a solution for everything, when I see him arguing and chewing, spitting and cursing, I k now it won’t be long before the sheriff gets him; and there are too many of his class, his type is seen in other forms…” Sunday continued that in the present day, everyone shifted the blame from themselves to something else, but the reverend refuted this fiercely decrying, “When things go wrong, the people, not God, are to blame. Citizens of Joplin, you are to blame. Citizens of Joplin you are to blame.”

Sunday asked the question, was a revival worth it? Was even an improvement of six months’ work worth it? The reverend answered in the affirmative, “It is worth all a person owns to have peace and contentment brought to the home for six months. It is worth much to a woman to have her home made bright and to have her husband come home sober instead of having him brought in drunk to curse and damn her.” Even if the husband fell off the wagon, Sunday proclaimed, “It will be appreciated, you can’t tell me it won’t.”

Sunday, as he began, “…dramatically hooked his clinched fist through the ozone and declared he was in position to defend himself and his policies.”

The reverend then directly addressed the work ahead for the city, “Joplin has an enviable reputation throughout the country. It is recognized as a hustling, bustling city. It is looked upon as a place of money. But there are knockers here as elsewhere. They are always busy with their hammers and they don’t observe union hours. When our lives are pure and there are those who are interested in the moral betterment of the municipality, a city takes to a revival just as water seeks its own level. There are experts in all lines, in medicine, in law. This is the day of specialists, and the evangelist is one of them; his work is different from that of a minister.” Sunday then explained that, “…a revival is the conviction of sin. Inside the church there must be a spiritual revival before it gets outside.” The problem, Sunday continued was that,”…the average church worker’s faith is almost ready to snap; the average citizen spends too much of his time in his commercial interests. In Joplin there are many people devoting all their time to zinc mines and zinc mining stocks and letting their kids go to hell.” Sunday then condemned, “You can walk down the street with a basket of nickels and lead four-fifths of the people to hell.”

Sunday also addressed the subject of the local minister. He accused preachers of being unforgiving and so caught up in factionalism with other reverends that they were just as quickly find themselves on the way to hell as any other sinner. Some of the biggest devils, Sunday growled, were baptized. For Sunday, salvation was found through faith in Jesus Christ, not in organized religion. Churches were fine so far as they were “in the world, but all wrong when the world is in [them]…” Sunday then proclaimed, “You can go to hell just as fast from the church door as from the grog shop or bawdy house.”

As the clock neared 9:30 pm, Sunday concluded with a catalog of those who would fight against the revival. They were the blackleg gamblers, the bartenders and saloon proprietors, and prostitutes, as well nefarious and slinking politicians. None the less, Sunday declared, “But I’ll give the devil and his gang the best run for their money they have ever had.”

Thus, Sunday had established the battleground upon which he intended to fight. Like many of the pre-Prohibition evangelist of the day, alcohol existed as one of the chief evils of society. Remove it and those who supported its distribution and a society would be down the path to peace and happiness. It was one of the chief pillars of vice that Sunday fought against and would become an even wider electoral battleground in only a number of weeks.