“No other Chinaman in Joplin has ever enjoyed the distinction of being the mixer that No. 52 was,” the Joplin News Herald remarked, recalling the life of one of the city’s few Chinese residents.

Little is known about “No. 52.” According to an article in the News-Herald, “No. 52” was the nickname of a Chinese immigrant named “Sam Wung, or something of a similar sound.” He was born the son of a fish vendor in Hong Kong. After he fell in love with the daughter of a well-to-do Hong Kong merchant, Sam sought to prove himself worthy of her love. Despite his best efforts, Sam failed to acquire the wealth he sought. So he boarded a ship for the United States, arriving in Louisiana, and found work at a cotton plantation.

Sam found himself working in cotton fields alongside African-Americans. It was also in Louisiana there that he obtained the nickname “No. 52.” “When payday came he received his envelope marked 52. And the title stuck with him.” A man named C.B. Oats met Sam in Louisiana and brought him to Joplin to find work in the mines. When a miner asked, “What’s the Chink’s name?” Oats replied, “They call him No. 52.” The name stuck.

Sam spoke wistfully of the girl he left behind in Hong Kong, but declared he could not return because a group of white men had cut off his queue while in Louisiana. Chinese men were required to wear their hair in a queue [pigtail] in deference to the emperor. If a Chinese citizen disobeyed this order, it was considered treason, and the penalty for disobedience was death. Fearful he would be executed if he returned to Hong Kong, Sam hoped to save up enough money to send for his beloved.

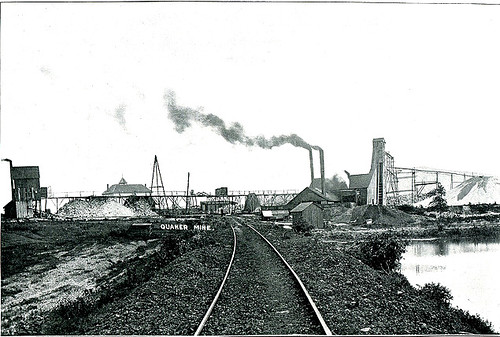

He found work in the mine of Monroe Clark and John F. Wise located on West Third Street just south of the Joplin Overall Factory near Byers Avenue. According to the News-Herald, Sam was the only Chinese immigrant to work in Joplin’s mines. It was explained that “Unlike his fellow yellow skinned brethren who contented themselves with cleaning dirty clothes and eating rice three times a day, No. 52 sought employment with white men, and despite his nationality he became a favorite.”

For “a number of years he labored with white men. Industrious, good natured, and honest, he won for himself an esteem that is seldom granted to Chinamen.” Impressed with Sam and his rapport with miners, John F. Wise offered him a position as a clerk in his grocery store, which Sam accepted. But even though he worked behind a counter, Sam would leave work in the evening to go to the mine and “spend many hours with the boys underground, chatting and telling stories.”

It was on one of these occasions that Sam stepped onto a tub to be lowered into the mine when tragedy struck. As the tub descended, the “can dropped suddenly a distance of fifteen feet, then stopped.” A cable had slipped on the whim [a whim was a large windlass]. Sam was jerked out of the tub and was “dashed to death” on the floor of the mine one hundred and thirty feet below. His broken body was retrieved and laid to rest in Fairview Cemetery. Sam’s grave was marked with a simple stone that read, “No. 52.”

His death brought sorrow to “hundreds of hearts for No. 52 was a popular Chinaman and he numbered his friends by his acquaintances.”

Source: Joplin News Herald