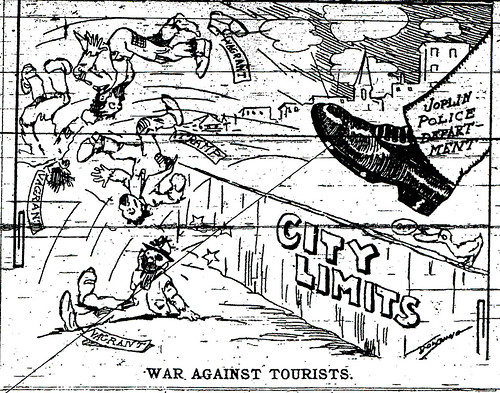

In years past, Carthage and Joplin have had an unspoken rivalry. Sometimes this rivalry would manifest itself in spirited jibes published in the papers, but more often than not it was the Carthage Evening Press that took swipes at Joplin, rather than the Globe or News-Herald that tried to besmirch Carthage’s reputation. The following article is one of hundreds of news items that the Evening Press ran over the years about incompetent, lawless, wicked Joplin.

“Lawless at Joplin. Many Robberies Occur Between the two towns — Police Protection Needed.

‘Kid’ Holden, who runs a gambling device in the Barbee building [Note to Readers: House of Lords] and lives on the corner of north Mineral and Hill streets, East Joplin, was robbed on Broadway, between East and West Joplin, Saturday night, while on his way home. The robbers were secreted behind the bill-boards on Broadway, between Virginia and Pennsylvania avenues, and as Holden approached he was clubbed into unconsciousness — the robbers taking a gold watch and pocketbook which contained $7. It is reliably reported that an attempt was made to ‘hold-up’ Holden some time ago, but he ran his assailants away with a revolver.

This audacious robbery has occasioned much talk in East Joplin, and has brought out the fact that there have been upward of a dozen attempts at ‘hold-up’ and robbery between the two towns within the past two or three weeks. A citizen of East Joplin says: ‘Crooks are to be seen almost nightly between Main street, on the west side and the bridge and its vicinity on the east side, where they are either skulking about the lumberyard, railway crossing, hiding about freight cars, the dives or shanties in the vicinity, or the bill boards.

‘Not long since,’ he continued, ‘an east town lady, while purchasing groceries on the west side, displayed a rather full pocket book in her rounds, she had not gone far on her way home before a robber approached her. But just then a car came gliding down the hill. She at once ran toward it, and the thief made a hurried break in the opposite direction, and was almost instantly out of sight.’

‘It would be a very easy job to ‘pull’ these ‘crooks’ and break up the robbers roost between the two towns, but no attempt has yet been made to afford any relief whatever. The crooks are actually safer between the two towns than any other part of the city.[Editor’s Note: The area between the two towns probably refers to the area known as the Kansas City Bottoms.] The police, or its chief, evidently consider it the duty of the force to remain about the crowded streets, and protect the saloons, and ‘pull’ those who patronize those institutions ‘too freely,’ and thus swell the city’s funds while leaving the various outlying thoroughfares of the city of Joplin utterly unprotected.’

‘It is claimed that if three picked men were taken off the police force, the remainder would not be worth a snap of the fingers. The force is the most incompetent in the history of the city. The recent east town shooting affair — when two policemen in attempting the arrest of an unarmed crippled boy over a twenty-five cent game of cards in a saloon, shot him down at close range — is an illustration.”

Source: Carthage Evening Press