Joplin’s newspaper reporters loved to write about the tramps and hoboes that often drifted through town. The lifestyle of the “weary willie” was one that reporters seemingly found colorful and romantic despite the hardships that many of the men and women who traveled the road faced on a daily basis. Long before the 1930s, and in a time when relief agencies were few and far between, hoboes and tramps often found themselves one meal away from starvation. On one occasion during an economic downtown, a News-Herald reporter sought out a hobo and asked him what the smallest amount of money was that he could live on.

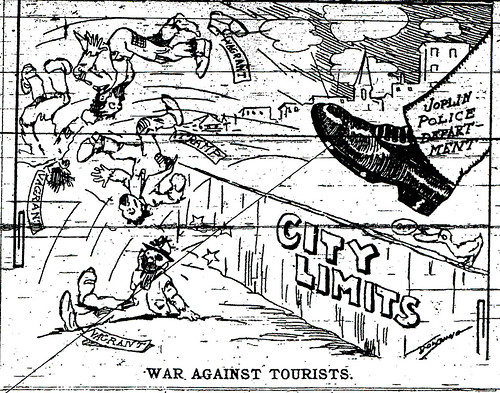

The hobo, after thinking for a moment, responded, “It is possible for me to live on 25 cents a day. I have lived on that amount but I did not spend any on it for a place to sleep. Of mornings, I would eat two chilies and for dinner, a ten cent pork chop. For supper, I would eat another chili.” To get the occasional piece of meat, the hobo would visit butcher shops and obtain meat that was otherwise reserved for feeding dogs. He would sleep in the woods rather than in town, lest he be picked up by the police for vagrancy. If a tramp or hobo were fortunate, he would sleep in boxcars, barns, or on railroad platforms rather than in the open.

When asked if he ever became desperately hungry, the hobo told the reporter, “I have been so hungry that I was too weak to walk, but did not become desperate. I felt that I was near the place where I would not have to spend from twelve to eighteen hours per day being turned down by people, with the world against me and no pleasure whatever.” Instead, he confided, “I also knew that after I reached a certain stage, people would feed me, for fear I would die on their hands.”

Joplin had more than its fair share of the “knights of the road.” There were individuals that loved the lifestyle, but there were others who found themselves riding the rails because of sudden, severe economic downturns that cost them their livelihoods. Funny how some things never change.