The Preparations for Sunday

While the ministers of Joplin were busy raising the tabernacle in advance of the arrival of Reverend Billy Sunday, other preparations were also underway. Among those was the organization of women to help reinforce the religious teaching of Sunday’s great revival through “cottage prayer meetings.” 112 districts were created which encompassed the city with at least one woman per district. While several meetings were expected to happen before Sunday arrived, thereafter, thirty-minute meetings would be held every Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday after the Sunday services to follow up on the sermons.

Preparations also were afoot in the office of the mayor, Guy Humes. At his behest, the chief of the Joplin Police Department, John A. McManamy, issued a notice to the department which read:

“To members of the police department: Gentlemen, I desire to call to your attention to the fact that boys are being allowed to shake dice in pool and billiard halls and saloons. This must be stopped. Second, that gambling houses are running in Joplin. These must be closed or the proprietors put in jail.”

Five days later, under the order of Mayor Humes, the Joplin Police under the cover of night, swept through the district of the city between Eighth and Ninth Streets. Their orders were to investigate “suspicious houses,” where a newspaper claimed “questionable resorts were being maintained in buildings” on the block. The investigation netted two women, Bessie Cook and Anna Grimes, arrested on the charge of “lewd conduct.” (Both pled not guilty) Before the specter of Reverend Sunday’s pending arrival, another raid was executed this time on “joints” on Main Street at nine in the morning on the 15th of November. Three squads of Joplin Police officers worked their way through suspected locations and by noon had arrested over 68 women (similar arrests resulted in $10 fines and a charge of disturbing the peace).

Since his election, Humes had struggled to rein in the vices of Joplin, but often had met with resistance. One Joplin daily newspaper (which threw its political support to the party of Humes’ opposition) even made a habit of ridiculing Humes’ morality crusade. Regardless, the fact that Billy Sunday was coming to Joplin had provided the mayor with a new well of support to achieve his goals. It was with no surprise that with such a groundswell of backing that Humes selected the most (in)famous saloon in Joplin to personally raid, the House of Lords.

By law, alcohol was not to be sold on Sunday, a Joplin blue law. It was also a law that newspaper articles implied was routinely flouted. In his effort to ensure that he could catch the proprietor of the House of Lords in the act of breaking the law, Humes made the controversial decision to hire private investigators to go undercover to alert him of the time and practice of the violation. Thus armed with said information, Humes personally lead a raid into the famed saloon accompanied by not just police officers, but also a newspaper reporter. The result was outrage by some and congratulations by others and space on the front page of a Joplin daily.

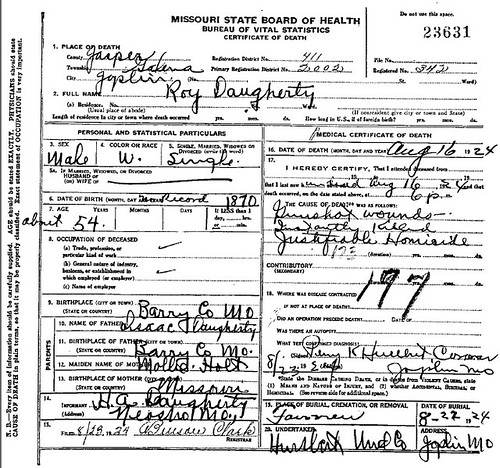

The city’s crusade was not without violence and bloodshed, either. In the midst of the prior raid on suspicious women, one police officer was killed and another wounded by William Schmulbach, when an attempt was made to arrest his wife. Schmulbach escaped and became one of Joplin’s most notorious and wanted men. High rewards failed to turn others against him and Joplinites claimed to have spotted him at one time or another across the breadth of the nation. Chief McManamy blamed the municipal judge, Fred W. Kelsey, who had ordered the raid for the officer’s death. Judge Kelsey, likewise accepted responsibility, but fired back that “No officer should shirk the responsibility of a raid made in an effort to enforce the law…” The severity of the conflict by Humes against the vices of Joplin soon garnered the attention of the Kansas City Star, which sent a reporter to Joplin to report on crackdown.

In the outsider peering in perspective offered by the article that ensued, the true state of the recent events took on the incredible air of a city government divided. In one corner was the mayor, whom the article referred to as supported by “those who desire to see the laws enforced.” In another, the long time and often re-elected chief of police, McManamy, who purportedly was lobbied by the ne’er do wells to simply allow the city to be policed as it had before the pre-Sunday enforcement push. In the third corner, the municipal court judge Kelsey, who in contrast to Humes, wanted an even stricter crackdown on criminals. Additionally, the city council of sixteen was also divided along even lines of support for and against the law enforcement effort.

It all, the paper claimed, was due to the eventual arrival of the Rev. Billy Sunday. His arrival, “caused a shiver to run through the camp of the lawbreakers.” Purportedly, such was the concern of those on the wrong side of the law that a meeting was held at the House of Lords where a temporary agreement was made “…The gamblers agreed to leave town for a while and the saloon keepers decided to close their places on Sunday while the revival was in progress.” Thereafter, as soon as the revival and the excitement it generated ended, the gamblers would “slip back again.”

The House of Lords was, the paper described, “The central point of attack of the law enforcement contingent and the place around which the defenders of an open town are rallying…[It is]…the pioneer saloon, café, pool hall and rooming house in Joplin. It is the headquarters of many of the politicians, and the stronghold of those who do not like to see old conditions disturbed…” The House of Lords was a place of “red paint and expensive furnishings” which separated and distinguished the saloon from any similar business in Joplin. Humes, after the raid, refused to sign the liquor license and vehemently swore the House of Lords would be permanently closed.

On the left, the House of Lords, located at the very heart of Joplin’s financial district and the alleged heart of those who supported an “open town” policy for Joplin.

Rev. Sunday also brought fear to those who indirectly supported unlawful activity. “Some of those “church goers” who had been renting their buildings for rooming houses of questionable character and for dens of vice, took fright and demanded that their tenants vacate. The Rev. Mr. Sunday has a way of collecting local information and announcing publicly the names of offending church members. There was a general stampede for righteousness among that class of church members…”

The Reverend Frank Neff, formerly assistant pastor at the Independence Avenue Methodist Episcopal church in Kansas City, and then president of the Ministers Alliance of Joplin, stated to the reporter, “We expect a great clean up in the city, but it will be in the nature of a religious awakening which will result in a permanent clean up and will come from a sincere desire of the people.” Neff went on to offer his support for Mayor Humes’ activity and granted him credit for attempting to clean up Joplin since he was elected.

The pending arrival of Billy Sunday shook Joplin to its core. For some, it was the opportunity to save the city from vice once and for all through an up swell of religious fervor. For others, it was a direct attack on the customs and habits, if not livelihoods, of a city that had persisted since the birth of Joplin as a rough mining camp in the old Southwest. While factions fought, compromised and fought even more, all sides waited in one form of anticipation or another for the reverend to arrive.