In the immediate years following 1900, Joplin continued to aggressively expand with more mines, more buildings, more wealth, and more vice. Back alley crap shoots, billiard halls, saloons, bars, and brothels were common sights. Just like mining towns in the American West, Joplin had its share of soiled doves. In 1904, a mix of Victorian morals, a steady number of prostitutes, and petty crime led to the public to demand that the Joplin Police Department hire a police matron. A police matron, often an older woman, was placed in charge of female prisoners in the city jail. The Joplin city council responded to the growing problem in the spring of 1904 when it unanimously passed an ordinance that required the city to hire a police matron. The only hitch was that the hiring would have to wait until the next fiscal year as there was no money in the then city budget to pay the matron’s salary.

It was not until two years later, in 1906, that the city hired a police matron. Over forty eager women applied for the position, but many were quickly turned aside for lack of skills, deportment, and experience deemed necessary for a qualified police matron. The field of candidates was narrowed down to three women: Mrs. Dona Daniels, matron of the city’s children’s home; Mrs. Agnes Keir, who oversaw Joplin’s chapter of the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA); and Mrs. Ellen Ayers. Mrs. Daniels refused the offered position. Mrs. Keir had her admirers and fans amongst the members of the YWCA, who all threatened trouble to the city council should they attempt to steal her away. Through the process of elimination, Mrs. Ellen Ayers was selected as the successful applicant.

Pictured here, Ellen Ayers took on the role of police matron at the age of 64.

Described by both a local Joplin paper and the city council as highly qualified and trained for the position, Ellen Ayers’ appointment was closely followed by the newspapers. She was described as a “kindly faced, white haired woman of 64 years,” originally from near Portsmouth, Ohio, and moved as a young child several times, first to Trenton, Missouri, and then to Pleasant Hill, and finally to Paola, Kansas. The uncertainty of safety found in the border counties between Kansas and Missouri prior to the outbreak of the Civil War may have been the reason her family moved temporarily to Kansas City, only to return after the war ended. During the war, Ellen Fields, as she had been christened by her parents, met Felix M. Ayers, whom she married in 1864. A farmer and Union veteran from Kentucky, Felix was gave up his plow for the miner’s pick and moved his family to Joplin in search of a more prosperous life. He worked as miner until his health failed him, which may have prompted his wife to take on the candidacy of a police matron.

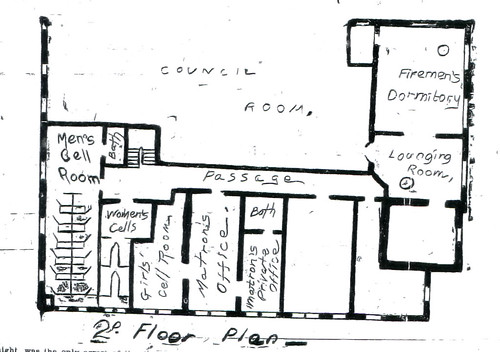

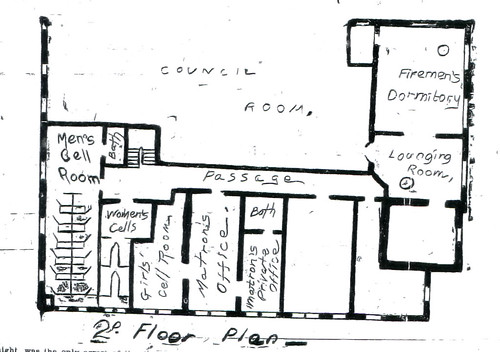

Although she was selected sometime around the end of 1906, she had to wait several weeks due to the fact that the city, despite the passage of the ordinance two years earlier, was still not ready for its new police matron to assume her duties. On November 27th, Mayor C.W. Lyon formally recommended that she begin her duties, which some hoped would allow the Joplin police to “much better work” at in “exercising influence to restrain wayward feet.” It was not until December 1, 1906, that Mrs. Ayers officially began her job looking after the female prisoners of Joplin’s city jail. While she had a residence at 1922 Pearl Street, an office and private apartment were prepared for her on the second floor of the city building, which was shared by both the city’s police and fire department. Described as inexpensive but “substantial” the paper promised a certain amount of coziness for its inhabitant. Adjoining her living area was a wooden door, built to conceal a barred one behind it which had a cement floored cell for female prisoners.

Floor plan for the second floor of the Joplin Police station, which also served as the fire station and city hall.

Mrs. Ayers approached her job nervously, admitting that the work was new to her, but professed her resolute determination to do a good job. While unaware of what was entirely expected of her, she told a reporter that she thought that “firmness and kindness” were the most essential elements of her job. Likewise, it was thought that the new police matron would provide motherly reassurance to the wayward women of Joplin. Mrs. Ayers was the mother of four children; the only surviving child, a daughter, was Mrs. Myrtle Gobar. One of the duties assigned to the police matron was inspection of the food served to the women, and on her first go Ayers quickly rejected a breakfast for her first charge, Nettie Waters. Declaring the meal inedible, the police matron demanded a new one. Nettie may have appreciated the care, but unfortunately did not get to experience much more of it as she was ordered off to the State Industrial School for Girls in Chillicothe for a year.

One week and twenty-four women later, a reporter caught up with Mrs. Ayers to obtain her reaction to her new job. It was a job, Mrs. Ayers said, that demanded constant attention and required her presence nearly twenty-four hours out of the day at the city jail. With the exception of when she left on business or for meals, the police matron found herself always in the city building. The most striking and shocking revelation for Mrs. Ayers, was the “depravity” of the women she encountered. While ages varied, many of the women were jailed for prostitution and street walking. Of their vices, the police matron complained that many were addicted to cigarettes and “coke.” Coke in this sense was the local term for morphine and cocaine. She estimated two-thirds of the women were addicted to either morphine, cocaine, or both. The police matron experienced the needs of an addict in one of her first days when a new arrival grew terribly sick and demanded a physician.

“She awakened me with the most painful screams. I went to the door, and she was crying loudly, and complained that she was very sick. I immediately went down stairs to see about getting a physician but the officers informed me that it wasn’t a physician she wanted, but rather some morphine.”

Beyond the dark and depressing side of Joplin’s prostitution problem, she also encountered women who arrived at the jail for other reasons. One was a young girl, perhaps 16 or 17, who to Mrs. Ayers dismay constantly smoked during her conversations with the police matron. Another girl was Alma Richards. Described as appearing to be 14 years old, despite being much older, and possessing “dark eyes,” the girl had been to the Missouri State School for the Deaf and Dumb in Fulton, and despite being ascribed those qualities, communicated to Ayers through writing. By this communication, the matron explained, she learned that the girl refused to go home due to the presence of an abusive father, who reportedly brutally beat her after she broke a window. Alma’s presence at the jail caused its own news, as the city did not want to release her, and the Industrial School at Chillicothe refused to take her as she was older than 18 and reportedly, “unmanageable.” Alma Richards’ fate is unknown.

This building served as Joplin's city hall, fire station and police station. Mrs. Ayers' office was likely along the left side of the building pictured here.

For three more years, Ellen Ayers performed the role of matron for the Joplin Police Department before leaving the position in 1909. After a period of time, she was replaced two years later in 1911 by Vernie Goff who worked the job until 1914.

As for Ellen Ayers, at some point before 1920, her husband Felix passed away. In 1920, she lived a widow with either a nephew or niece, but by 1930 had her own room in a boarding house at age 87. Despite the trials and undoubted stresses of the position as Joplin’s first police matron, Ellen Ayers did not let the job overwhelm her and hopefully lived the next 20 years of her life knowing she made a valuable contribution to her community as the city’s first police matron.

Sources: 1880, 1920, 1930 United States Censuses, Joplin Daily Herald, 1918 History of the Joplin Police Department.