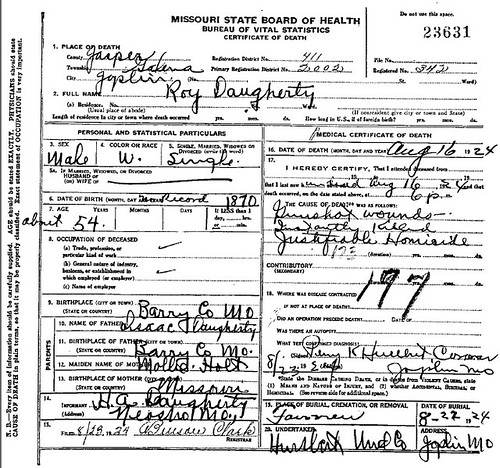

The end of an era came to a close when, on August 16, 1924, Joplin Police Detective Lee Van Deventer shot and killed Roy Daugherty. Daugherty, a member of the fabled Wild Bunch, met his end when Van Deventer shot him just above his heart as a young child clung to his leg. The mortally wounded bandit staggered, then collapsed onto a nearby bed, and died. With his death ended a saga of the Wild West that began in 1870 in nearby Barry County, Missouri, where Daugherty was born.

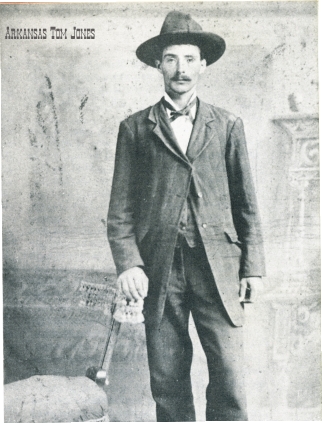

At the age of 14, Roy Daugherty ran away from home to Oklahoma. It was there that he adopted the nickname “Arkansas Tom Jones” and fell in with Bill Doolin of the famed Doolin Gang. A string of subsequent robberies ended with the “Battle of Ingalls,” in a saloon in Ingalls, Oklahoma, when United States Marshals under the command of E.D. Nix sought to capture the Wild Bunch. It was a bloody gunfight that ultimately left three marshals and four outlaws dead. Daugherty was captured when James Masterson, brother of legendary lawman, Bat Masterson, hurled a stick of dynamite at the outlaws and managed to stun Daugherty long enough to arrest him.

Legendary United States Marshal E.D. Nix who oversaw Daugherty's capture at the Battle of Ingalls.

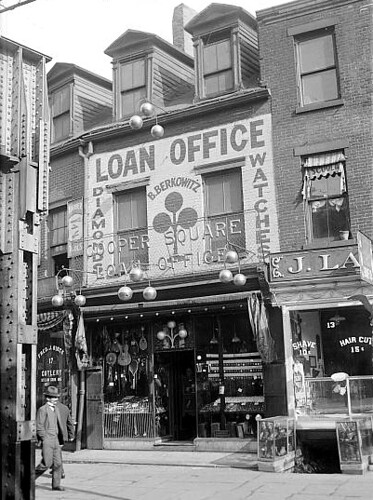

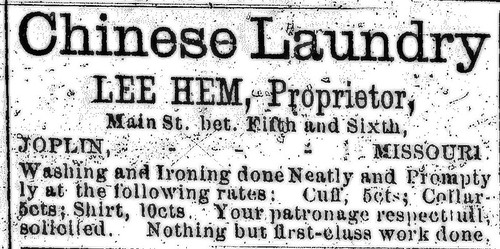

Daugherty was sentenced to prison for 50 years, but was released early. It wasn’t long before he returned to a life of crime. It was approximately 1901, after an arrest, when Daugherty’s first recorded visit to Joplin may have happened, purportedly as an unwilling participant in a traveling exhibit of the Wild West. It is entirely possible this event never happened, but the lifelong outlaw did find his way to Joplin in 1917.

While much of Daugherty’s criminal career happened in neighboring Oklahoma, by 1917, it was rumored he had played a role in a series of robberies in Missouri, including a bank job in the small town of Fairview, in neighboring Newton County. In 1917, Joplin police detectives William F. Gibson and Charles McManamy sought him for robberies in Oronogo and Wheaton, Missouri. Their investigation led them to a farmer who, after an hour of intense interrogation, finally confessed the location of Daugherty’s safe house. The hesitation had not been out of loyalty, but for fear that the outlaw would seek vengeance for the betrayal of his location.

Possibly out of doubt of their informant’s confession, or perhaps for lack of a better plan, the Joplin detectives simply knocked on the door of the house in which Daugherty was reportedly inside. It may have come as shock when the outlaw opened the door himself, but if the men were surprised, the moment quickly passed as both lawmen charged into the house to arrest Daugherty. Daugherty stumbled back into the house, while McManamy and Gibson rushed after him, and the three found themselves caught in a moment of hesitation focused around a revolver that lay on a nearby table. All three men lunged for the weapon, and had Daugherty been the quicker, the stories of Detective Gibson and McManamy might have ended that day.

Gibson reached the pistol first. Daugherty, who seemed to have known the detective, reportedly said, ” I’m glad you got it, Billy. If I had beat you to it, I would have had to kill you.” And so, the Barry County native was returned to prison courtesy of the Joplin Police Department and sentenced to 8 years. Daugherty, despite being a former member of the Wild Bunch with a string of robberies to his name, was released early on good behavior. If Daugherty had served his entire prison term, it is entirely possible that the events of August 16, 1924, might have never happened.

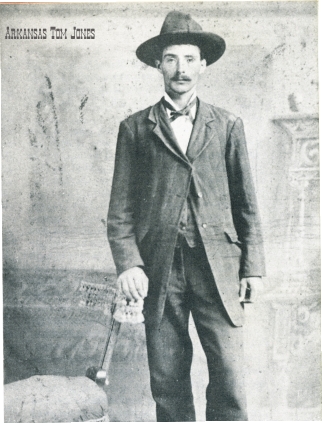

Roy Daugherty in the prime of his life. Via Wikipedia.

Some things had changed since 1917. Joplin detective, William Gibson, had been promoted to Chief of the Joplin Detectives. Likewise, some things had not changed, such as Roy Daugherty’s penchant for robberies. This time it was a bank in Asbury, a town on the Kansas — Missouri line, just northwest of Joplin. The Joplin police sought out the 54 year old outlaw, and were tipped off to his location on a hot Saturday afternoon. Once more, William Gibson set out to arrest Daugherty, accompanied by fellow detectives Len Van Deventer, Tom DeGraff, and Jess Laster. Chief of Police Verna P. Hine also joined the detectives.

Word was that Daugherty was in the home of a Joplin local known as “Red” Snow at 1420 W. Ninth Street. The plan was simple. Two cars, one with Gibson and Van Deventer, the other with DeGraff, Laster, and Hine, would speed to a stop in front of the home and the men would rush the house. Afterward, Detective Chief Gibson reflected on his thoughts as the lawmen left to capture Daugherty:

“I knew there would be trouble when we left the station to get Daugherty. I knew we were after a man who had shot first in eighteen fatal encounters and I expected no surrender. Daugherty would die with his boots on and I believed that someone else would unlace them tonight.”

As the police neared their destination, the car in which Police Chief Hine was riding in veered off a block early. At that point, Gibson believed that Hine had elected to stay out of the capture, a claim that Hine later denied. When Gibson arrived, he headed for the rear of the house, convinced that Daugherty would try to escape out the back. Gibson described what happened next to a reporter:

“I saw him [Daugherty] through a window as I ran toward the back door to cut off his escape, and I knew then he knew that it was to a finish. He ran crouched, to present as small a target as possible, his gun clutched in both hands before him. I reached the porch in the rear of the house and met him at the door.”

At that point, Daugherty opened fire point-blank on Gibson. Gibson later was at a loss as to how he was not hit by the outlaw’s fire, especially after he discovered a bullet hole in his hat. Gibson sought cover behind a nearby bush and returned fire. Three of his bullets hit their intended target. Daugherty was hit in his left wrist, his right side above the kidney, and was grazed on the side of his head above an ear. Sufficiently discouraged from escape out the back door, Daugherty headed for the front.

As Daugherty did so, Red Snow’s wife, caught in the middle of the gunfight, screamed loudly. He did not get far. In the time in which Daugherty and Gibson had exchanged shots, Detective Van Deventer entered the house through the front door. The two found themselves in a face off and the younger Van Deventer fired first. The large .44 caliber slug from Van Deventer’s revolver struck Daugherty in the chest and the man who had rode with the Wild Bunch fell dead onto a nearby bed. At his feet, the young child of Red Snow bawled, confused and frightened.

After confirming that Daugherty was dead, Van Deventer and Gibson helped themselves to two cigarettes from the dead man’s shirt pocket. His body was sent to the Hurlbut Undertaking Company and reportedly attracted the attention of thousands who came out to view the corpse of the famed bandit. Later it was discovered that Daugherty’s .38 revolver had jammed after he had fired only two shots at Gibson, which might have been a reason that both Gibson and Van Deventer had emerged unscathed in the ordeal.

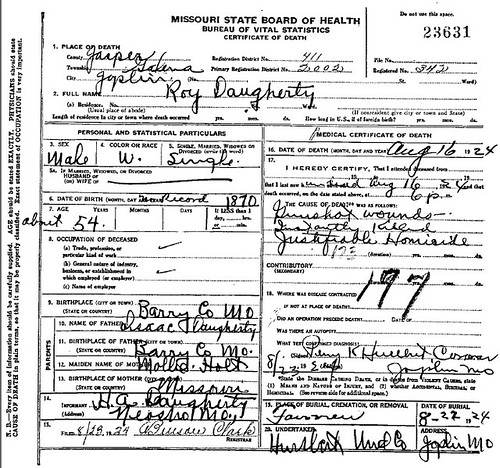

Roy Daugherty's death certificate.

Daugherty’s death brought about the resignation of the Joplin Police Chief Hine. When the police had set out to capture, Hine’s car had turned away a block too early. Hine later stated that he thought he was supposed to go to the rear of the house to cut off escape. Hine was later accused of cowering behind a barn while Gibson shot it out with Daugherty. The police chief claimed he had thought Gibson had been shot dead, when the detective had only crouched for cover, and thus had paused in his approach toward the house. Hine also argued that he had never even paused, but the entire time had been on a slow approach to the house; slow only because of high grass that had grown up in the rear of the property. His explanations were not enough. Joplin Mayor F. Taylor Snapp publicly called the police chief a yellow coward and demanded his resignation.

Ironically, Hine, a former barber, had been appointed by Mayor Snapp two years before, his only experience was having served as a special park policeman in Schifferdecker Park and six years on the Joplin police force. His inglorious end as Joplin Police Chief came only two days after the gun battle when Hine handed in his badge..

Roy Daugherty was not the first notorious gunslinger to visit Joplin, nor was he the last infamous outlaw to come to the city. In less than ten years, a modern successor to the Wild Bunch rolled into town, headed by two outlaw lovers commonly known as Bonnie and Clyde. Unlike Daugherty, the Barrow Gang escaped fate in a hurried departure from Joplin, but that is a story for another post.

Sources: U.S. Marshals website, the Joplin Globe, and Digital Missouri.