In turn-of-the-century America, teams of “Bloomer Girls” traveled across the country challenging men’s amateur, semi-pro, and professional baseball teams to exhibition games. Despite being nicknamed for the loose-fitting trousers that they wore on the diamond, Bloomer Girls were tough competitors. One such “Bloomer Girls” team arrived in Joplin in June 1898, to play a series of seven baseball games against McCloskey’s Giants at Cycle Park. Interest was so intense that promoters added additional seats in anticipation of large crowds of spectators.

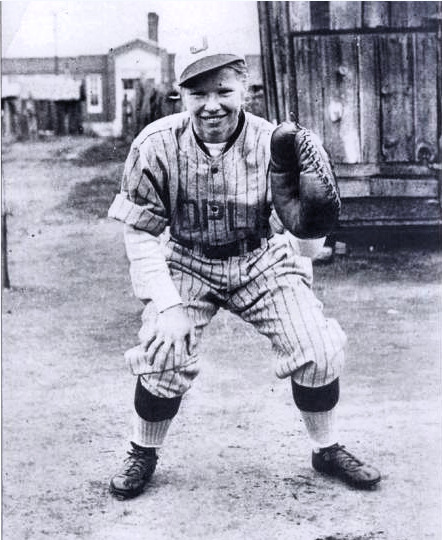

Maud Nelson, star pitcher for the team, was hailed as “a twirler of exceptional speed, and it is a common occurrence for her to strike out the strongest batters on the opposing team.” Nelson, a native of Chicago whose real name was Clementina Brida, grew up playing baseball with her brother. As a pitcher, she was reportedly paid $250 a month.

Although the Bloomer Girls engaged in athletic competition with men at a time when women were still governed by stifling Victorian mores, their manager assured the Globe’s reporter that the Bloomers were “refined ladies, most of whom learned the art of ball playing on account of it being a health giving exercise, and only adopted it as a profession after becoming experts and receiving flattering offers to play in exhibition games.”

McCloskey, manager of the opposing team, asserted that the Bloomer Girls came “highly recommended, both as to their excellent playing and conduct on the diamond.” Potential spectators were assured that “the management guarantees that nothing will be said or done but what the most refined lady in the audience will approve.”

In one of their games prior to coming to Joplin, the Bloomer Girls played the Eurekas, a local men’s team in Richmond, Virginia. The Eurekas were warned that the Bloomer Girls “asked no favors, and wanted the game played on its merits.” Captain Boyne, manager of the Eureka team, instructed his players, “to knock the Bloomers silly.”

Whatever preconceived notions the men of the Eureka baseball team may have had about women baseball players were quickly overturned when it was found that it “would be no easy matter” to beat the Bloomer Girls. By the end of the ninth inning the Bloomer Girls led the Eurekas 11 to 5. Maud Nelson was hailed as “a peach, her work in the box alone is worth the price of admission to the game.” She “handles herself like a professional pitcher, throws well, gives the catcher curve signs, and can stop or catch a ball with either hand.”

A 1901 cartoon of the Bloomer Girls from the San Francisco Call.

When the Bloomer Girls played McCloskey’s Giants at Cycle Park, they faced fierce competition from the Giants, who played as if “they had reputations to lose.” Managers McCloskey and Menefee livened up the game by having their men run between bases with the Bloomer Girls in hot pursuit. Unfortunately for the Bloomer Girls, they lost the first game 14 to 1.

Maud Nelson, who was “justly” billed as the “star of the team,” continued to be involved in baseball for years to come as a manager and team owner, anticipating the time when the women of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League.

Sources: The Joplin Globe, the Library of Congress, www.Exploratorium.edu, Wikipedia: Maud Nelson.