Distinguished historian Richard Hofstader observed in his book, American Violence: A Documentary History that Americans have a “remarkable lack of memory where violence is concerned and have left most of our excesses a part of our buried history.”

Like most cities across the country, Joplin has had its share of wild and wooly episodes throughout its history, though most of these events have faded into the past. The most common story that has stayed with us, perhaps because of their perceived glamour and mystique, is that of Bonnie and Clyde.

Perhaps a more harrowing story is that of what happened in Joplin during the hysteria of World War I. During this time, stories of German spies, disloyal citizens, and labor unrest created an atmosphere in which communities could turn upon their own. Joplin was no exception.

Gustav A. Brautigam, the owner of a delicatessen and bakery at 305 Joplin Street, was a native of Frankfort Germany. In 1881, he immigrated to America, and eventually arrived in Joplin. Brautigam was by no means the first German in Joplin.

Germans had been in Joplin since the very beginning. According to Joel Livingston’s history of Jasper County, “It was a German who built the first bakery in the city and a German who interested in the organization of the first bank in Joplin. In many ways the sturdy sons of Germany have taken a great part in the building and developing of the city.” In 1876, when the Germania Social and Literary Society of Joplin formed, it had over fifty charter members. Thus it was a small, but established German community, that Brautigam discovered upon his arrival in Joplin.

As Brautigam prepared for business on a Saturday morning during the height of World War I, he found that during the night someone had painted his store windows bright yellow. There were also warnings not to remove the paint from the windows. One warning read, “This place is pro-German. Take notice, Americans!”

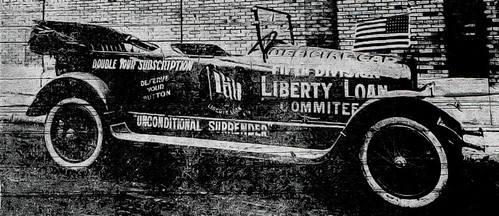

The 59 year-old Brautigam may or may not have already been the subject of controversy as rumors alleged he had previously declared that he hoped, “to live to see the day when the German flag replaces the Stars and Stripes on top of the Joplin post office building.” Despite such rumors, Brautigam had participated in the Third Liberty Loan, as he was permitted to hang a flag honoring his contribution to the loan fund drive in the window of his deli, as well as one from the Red Cross.

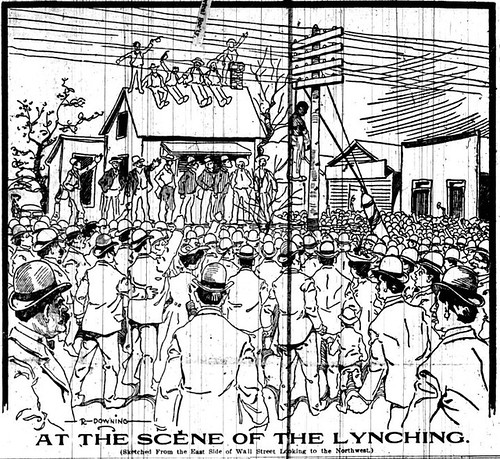

Upset, Brautigam began to clean the paint from his windows. As he did so, however, an unnamed individual stepped forward with a bucket of paint and began to repaint the window “as fast as it was washed.” A crowd began to gather to watch. Witnesses later disagreed whether or not Brautigam made disloyal remarks as he washed his windows. The crowd began to grow and soon it numbered an estimated 400 people. Brautigam, worried for his safety, went inside his delicatessen and locked the door.

The mood of the crowd remained uncertain until someone broke through the front door of the delicatessen and entered the building in order to rip down an American flag hanging inside the front window. At this point, Brautigam, fearing for his life, dashed out the back door of his business and escaped down the alley between Main and Joplin streets to the Joplin Police Department.

As he did, the crowd, now an angry mob, chased after him. Fortunately for Brautigam, he reached the safety of the police department before the mob caught him.

Upon alerting authorities to the situation, Brautigam was “arrested for his own safety” by the Joplin police. He asked Police Matron Wathena B. Hamilton to take charge of the perishable foods in his store and distribute them to those in need. She was able to assist eleven families in addition to the children at the Children’s Home. Brautigam was then transported to Carthage under guard and turned him over to Jasper County Sheriff Oll Rogers. Sheriff Rogers released Brautigam because “there was no charge on which they could hold him.” Brautigam reportedly then left Carthage by train.

After the mob discovered the Brautigam was out of its grasp, its members formed an impromptu parade. At the urging of an unnamed individual, the unruly mob decided to march on the Joplin Sash and Door Works located at Twelfth and Wall streets to “get” Peter Braeckel, the newly elected president of Joplin’s Germania Society. Only half of the mob made it to the business and the remainder was persuaded by James M. Leonard, identified as one of the original leaders of the mob, to calm down. Braeckel emerged from the Joplin Sash and Door Works to make a short speech to the mob in which he proclaimed his loyalty to the United States. It was reported that Braeckel’s words “had a great deal to do with quieting it.”

James Leonard informed the mob that Braeckel had contributed to the Red Cross “nearly all of the tables and shelves at the society’s headquarters and how he had made a screen door for the local selection board and sent a man to place it in position.” Leonard also told the mob that Braeckel had contributed “to every war work campaign and public charity campaign that had been conducted” in the recent past. Leonard was joined by an unnamed man who “turned squarely about and instead of advising violence, counseled calmness and helped to disperse the crowd.” It was only when Leonard pointed out a man who demanded they paint Braeckel yellow and declared, “It’s just such remarks as that one and such fellows as you that are going to cause this country as much trouble as Germany does” that the crowd finally dispersed.

Word of the mob interrupted a city council meeting, but officials quickly leapt into action. Joplin Mayor C.S. Poole and Chief of Police J.J. Cofer ordered all Joplin saloons be shut down immediately for fear that alcohol would only fuel the smoldering fire of potential mob violence that threatened the city. The entire police force was ordered out to patrol the city in addition to all available constables and deputy sheriffs.

City and business leaders met at the Joplin Chamber of Commerce and adopted a resolution to request that saloons be kept closed and that Home Guards be dispersed to deal with any potential violence. Among those present were: Sheriff Oll Rogers, Albert Newman, Haywood Scott, Mayor-elect J.F. Osborne, R.M. Shepard, Hugh McIndoe, J.J. Cofer, Burt W. Lyon, Sol Newman, O.P. Mahoney, G.F. Newburger, P.E. Burress, and E.A. Norris.

Captain Frank W. Sansom of the Home Guards mobilized a squad of forty men to patrol the city. Each man was armed with revolvers and Springfield rifles. Chief Cofer gave the home guard authority to make any arrests necessary to preserve law and order. Fortunately, the day and ensuing night were peaceful and without incident.

Although Brautigam eventually returned to his business and remained in Joplin until his death in 1956, the damage had been done.

A short time later, Joplin’s Turnverein Germania Society, led by its president Peter Braeckel and vice president Gustav Brautigam, voted to disband the organization and donate its property located on the southeast corner of Third and Joplin streets to the local Red Cross. The property was valued at $25,000.

The group issued a statement which read in part:

“Pioneer conditions, such as existed twenty, forty, or sixty years ago, and which forced people of a class to band together and create livable conditions are things of the past and can never reoccur. German immigration has diminished from year to year.

All German societies, as such all over the country are, and were at the beginning of the war, on a decline. About 50 percent of our present members are American born. At our business meetings of the past few years, we seldom had many more than a quorum (nine members). The Verein is dying a natural death. It has outlived its usefulness. The fact that we had the property held us together. The older members sometimes paid it a visit by force of habit — and the younger members did not come at all.

Germanism in this country, even if the war stopped today, will have no prestige for several generations. Too much harm has already been done. We must realize the vastness of the change of conditions. Never in the history of the world has our situation been duplicated. It is a unique situation, but it is a surprisingly clear and plain situation: We left one country. Why? Because we were not satisfied with our conditions.

We entered another country with the full knowledge (unless we were lunatics) that we had to abide by the rules and conditions imposed by this new country. The new country was very lenient with us, we hardly knew that we were being governed.

To us this war comes like a bolt of lightning out of a clear sky. We are awakened from a dream, awakened to the realization that when we changed countries it was also our duty to change our sentiments and sympathies.

The object of our Verein is to advance German customs, German habits, and the German language. This is, under the conditions which have arisen, intolerable and impossible. Our countrymen cannot and will not and should not be expect to countenance the existence of our Verein.”

Thus came the end to an organization that had once included leading Joplin citizens such as H. Geldmacher, Charles Schifferdecker, G.W. Keller, and Edward Zelleken as members.

Sources: Joel Livingston’s History of Jasper County, Joplin News Herald