One can look at the northeast corner of Fourth and Main and wonder, what if?

Guest Piece: Chapters Erased from Joplin’s Architectural History – Leslie Simpson

CHAPTERS ERASED FROM JOPLIN’S ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY

By Leslie Simpson

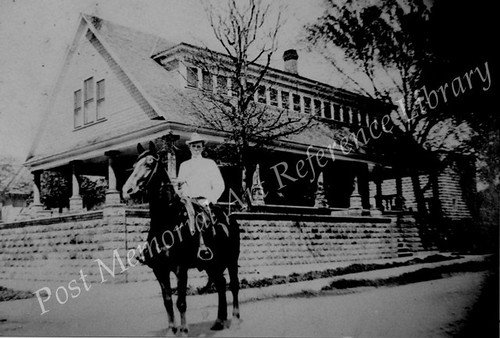

caption for photo: Carl Owen house at 2431 Porter. Built ca. 1911. Destroyed by tornado May 22, 2011 via Post Memorial Art Reference Library

I am having a difficult time knowing what to say. In fact, I hesitate to even write anything about brick and mortar, when human life, hopes, and dreams are what really matter. However, since I have written so much about Joplin’s architecture through the years, I feel compelled to say something. I have had several CNN reporters contact me for interviews, but I have not wanted to talk to them. First of all, I had not personally seen all the damage. It is impossible to get around, and I did not want to get in the way of emergency workers nor be a voyeur. Secondly, I just did not think I could articulate what has happened to my beloved Joplin. So now I will attempt some general (and unofficial) impressions of Joplin’s historic identity and how this incomprehensible tragedy has affected it. Also, rather than catalog specific buildings that have been lost, I will focus on three historic residential areas.

I begin with the historic town of Blendville in southwest Joplin, which was established in 1876 as “Cox Diggings.” The prosperous little community incorporated as Blendville, so-named because of the huge amounts of zinc blende in the ground. Thomas Cunningham owned the residential area, which he divided into lots and sold at low rates so that miners could afford their own homes. The city of Joplin extended its streetcar line to Blendville, with lines going south on Main to 19th Street, west to Byers, south to 21st Street, west to Murphy, then south to 26th. In 1892, Joplin annexed the village. Thomas Cunningham donated “Cunningham Grove” as Joplin’s first city park. The tornado took out most of the original Blendville area, including Cunningham Park and the historic water plant with some of the original equipment preserved inside.

The next area of historic significance is “Schifferdecker’s First Addition”, a residential area developed in south Joplin beginning in 1900. The Joplin Globe referred to the area lying south of 20th Street and fronting on Wall, Joplin, and Main Street as “a beautiful new addition affording the most desirable building property” to be found anywhere in the city. A second addition continued development south of 20th on Virginia, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania Avenues as well as along 21st, 22nd, and 23rd Streets to the east and west. The residential district continued to expand to the south throughout the teens, twenties, thirties. The homes in the region ranged from high Victorian styles to bungalows and eclectic Tudors, Colonial Revivals, Spanish mission, etc. Tragically, this charming old neighborhood has been wiped out.

After World War II ended, Joplin families faced a housing shortage. Some Camp Crowder buildings were moved to Joplin, while others were dismantled to provide construction materials. Hundreds of small efficiency houses were mass-produced for veterans and financed through FHA. Many of these were built in the Eastmoreland area. As people prospered in the 1960s and 1970s, they built more substantial brick homes east and south of the new high school at 20th and Indiana. Although most people do not think of these homes as historic, they do have their own place in Joplin’s architectural history, and their loss is devastating as well.

Entire chapters of Joplin’s history have been forever erased. I have not even touched on the loss of churches, schools, medical buildings, and businesses. Again, I am not relating the loss of our buildings to the loss of our people. Joplin will rebuild. It has already begun. During the first week after the tornado, I saw a business being rebuilt in the midst of the war zone surrounding West 26th Street!

Leslie Simpson, an expert on Joplin history and architecture, is the director of the Post Memorial Art Reference Library, located within the Joplin Public Library. She is the author of From Lincoln Logs to Lego Blocks: How Joplin Was Built, Now and Then and Again: Joplin Historic Architecture. and the soon to be released, Joplin: A Postcard History.

Guest Post: Down Not Out – Leslie Simpson

DOWN NOT OUT

By Leslie Simpson

On a pleasant Sunday evening, May 22, 2011, an EF-5 tornado suddenly raged through densely-populated south Joplin. It destroyed almost everything in its path for 13.8 miles in distance and up to a mile in width.

The tornado smashed down in southwest Joplin, wrecking residential areas, Cunningham Park, schools, medical offices, and a major hospital complex, St. John’s. It headed east, obliterating untold acres of late nineteenth and early twentieth century houses. The storm’s wrath intensified as it forged east, razing businesses along Main Street, more neighborhoods, and Joplin High School. It wiped out much of the lifeblood of Joplin’s economy, the commercial strip on Range Line Road, then rampaged on, demolishing housing, banks, industrial buildings, and more schools and churches. It finally dissipated east of Joplin, after destroying or damaging an estimated 8,000 homes and businesses.

At the time of this writing, authorities have confirmed 138 fatalities, a number which continues to rise. More than 1,150 people sustained injuries. The Joplin tornado, the deadliest since modern record keeping began in 1950, ranks eighth among the deadliest tornadoes in U.S. history.

We are in shock. We drive familiar streets yet cannot even recognize where we are. The cruel landscape of endless rubble and shredded trees reminds us of shattered lives and endless grief. We have lost so much, and we are hurting on many levels. But our spirit is strong, as evidenced by the person who spray-painted “Down not out” on the shards of his former home.

Leslie Simpson, an expert on Joplin history and architecture, is the director of the Post Memorial Art Reference Library, located within the Joplin Public Library. She is the author of From Lincoln Logs to Lego Blocks: How Joplin Was Built, Now and Then and Again: Joplin Historic Architecture. and the soon to be released, Joplin: A Postcard History.

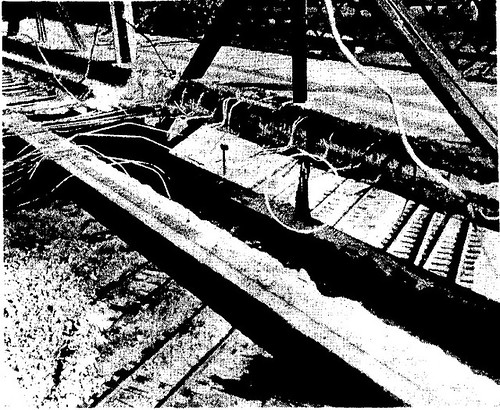

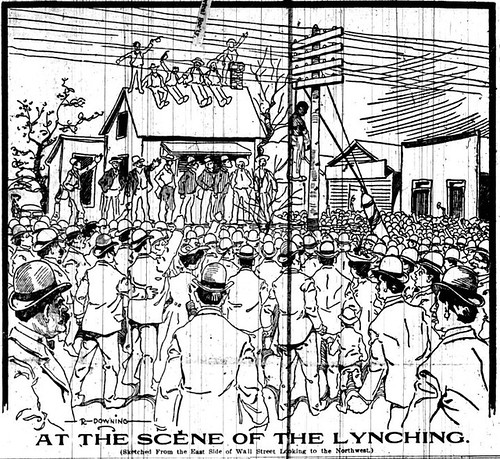

Second and Wall – Site of the 1903 Joplin Lynching

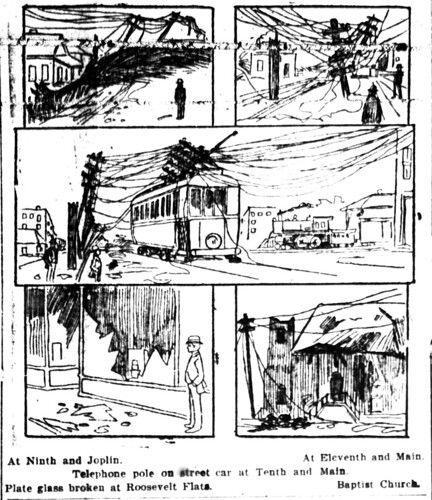

In anticipation of our coverage of the 1903 Joplin lynching, we bring you photographs of the location of the tragedy: Second and Wall. It was at this intersection that Thomas Gilyard was lynched from the arm of a telephone pole by a mob. First is a drawing of the lynching that was printed in the Joplin Globe immediately after the lynching. The artist was Ralph Downing, who later went on to be an artist for the Kansas City Star (where he worked the rest of his career).

The first photograph comes courtesy of the Post Memorial Art Reference Library and was taken just a couple months after the lynching, if not sooner.

The back of the photo read, "Joplin, Mo. June 17, 1903. This is where Bro. C.H. Button and myself lodged at the home of Mr. Wilson. The telegraph pole is where a negro was mobbed and hung last spring. Taken by Prof. C.H. Button, J.R. Crank. Taken at Bible School Convention." Courtesy of the Post Memorial Art Reference Library, Joplin Missouri

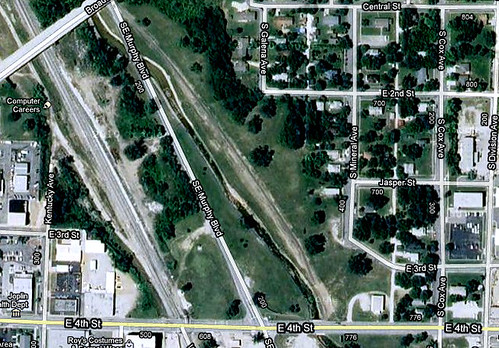

The next photographs were taken just last month, December 2010. Regrettably, the time of day and the position of the sun got in the way of nailing a photograph from the exact same position. For identification purposes, the only surviving landmark from the gruesome moment is the stone retaining wall which you will find in all the images.

If you don’t want to wait to learn more about the lynching, you can read about it in White Man’s Heaven by Kimberly Harper or pick up the most recent edition of the Missouri Historical Review.

Sources: Post Memorial Art Reference Library, Joplin Daily Globe, White Man’s Heaven by Kimberly Harper, and Historic Joplin Collection.

A Spring in Joplin

The Ozarks have always been abundantly blessed with springs, creeks, and rivers. Although Joplin’s neighbor to the south, Neosho, is hailed as the “city of springs,” Joplin was once home to the notable “Ino Spring.”

The Ino spring was located a half-mile west of Joplin near where two men, Frazier and McConey, had a brick ward in the early 1870s. The site became popular as Joplinites would drive out in the summer to cool off at the spring. The spring was described as a “stream of sparking water” that gurgled up from the side of a “slight uprising in the ground, not exactly a hill, but a knoll forming one side of a shallow gulley.” Joplin’s old-timers remembered the spring and it was tradition that “when the Indians roamed the prairie where Joplin now stands that they quenched their thirst” at the spring. By the turn of the century, it was “surrounded by numerous mining plants with immense pumps.”

The name of the spring came from the nearby “Ino” (I Know) Mining Company in upper Leadville Hollow. Reportedly the Ino mine was drained of water of almost 200 feet, but the little spring kept flowing. As Chitwood Hollow opened up to mining, it became known as the “Ino Spring.” Teamsters, lead and zinc haulers, coal haulers, and others stopped to water their horses at the spring as well as supplied water to the nearby Chitwood mining camp.

By the turn of the century, the citizens of Joplin were calling for pure water. In response, an unknown enterprising entrepenuer decided to haul water in from the Ino spring, despite competition from the Redell and Freeman “deep well wagons.”

It is unknown now if the spring still flows, we can only hope that it does.

Source: Joplin News Herald

Joplin Metro Magazine – Issue 6

We recently offered an approving review of the Joplin Metro Magazine for its coverage of topics of local history. The coverage continues with the 6th issue of the magazine designated as a Halloween / Fall issue. The issue focuses on Joplin’s resident Spooklight, though perhaps not delving as much into the past attempts to figure out the mystery behind the light, as well the earliest encounters. It’s still a good primer to anyone unfamiliar with the spooklight.

The best part of the issue concerned the survey of haunted sights and places in the Joplin area, which included short histories behind the locations. Such places included the old Freeman Hospital (with photograph), Carthage’s Kendrick Place (with photograph), as well Peace Church Cemetery, where one of Joplin’s most notorious murderers now resides in an unmarked grave. It’s articles such as this one which help show how fascinating the history right around one’s corner can really be. Last is an article about haunted Ozark battlefields. If you haven’t had a chance to read Issue 6 of the Joplin Metro Magazine, you might be able to still find hard copies located around town or you can read it online at this location (click here!).

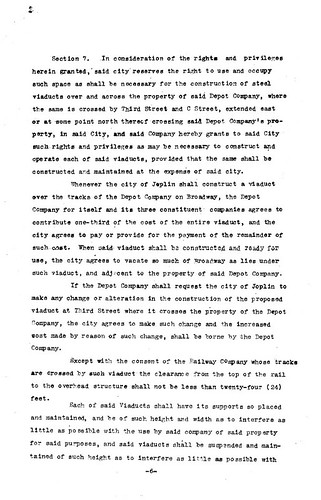

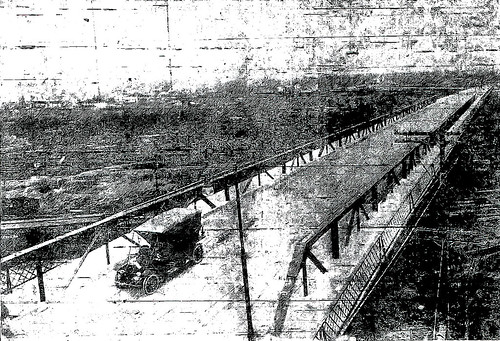

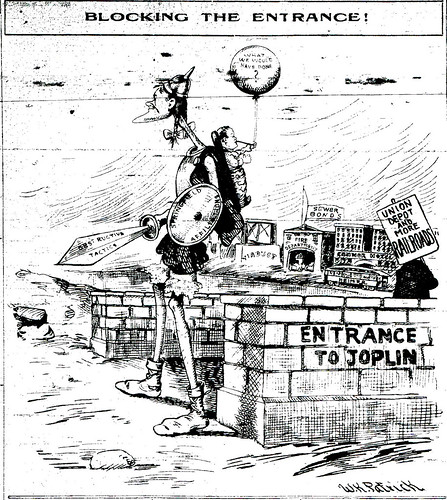

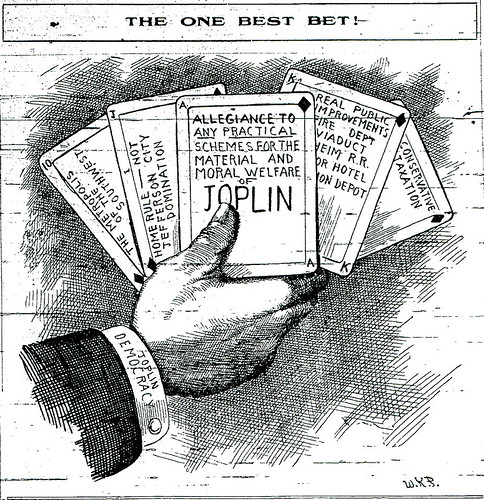

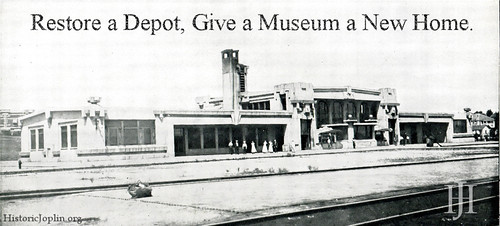

Globe Overview of the Union Depot

This last weekend, the Joplin Globe offered up a summary of the present situation with the Union Depot. In addition, the Globe put together a short timeline of events for the Depot from its opening over 99 years ago.

The summary covers in brief the past attempts at restoring the Union Depot, including an offer in 1973 by the Kansas City Southern to deed the Depot to the city. That proposal was nixed by the then head of the Joplin Museum Complex, Everett Richie. The excuse given then was the danger that the active train tracks posed to the museum and its collection should it be moved to the location.

The Globe managed to speak briefly with Nancy Allman, who was the lead in the effort to restore the Union Depot in the 1980’s. Allman did confirm that she still had in her possession some items from the Union Depot. This is good news for the restoration of the Union Depot. Even if Ms. Allman may not want to donate or sell the items, perhaps she would at least allow the restorers to photograph and measure the items for reproduction purposes.

The article also brings us via Allen Shirley the 3 Key Issues for the JMC about a move to the Union Depot. Let’s look at them one by one:

1) The Union Depot’s structural integrity.

Reports indicate that the work done in the prior restoration attempt went along way toward reinforcing and repairing structural integrity issues. In the walk through by the Joplin Globe with David Glenn, who was part of the restoration team from the 1980’s, Glenn comments on the strength of the building.

2) There’s less than 400 sq foot than the current museum.

As we’ve pointed out in previous coverage of the Union Depot question, there are two measurements being offered of the Union Depot’s space; one from the JMC and company, and one from Mark Rohr. It really boils down to the basement. One side counts it and the other side doesn’t. The basement also brings about another issue, as we’ll address below. There’s no reason more space cannot be constructed to supplement the Union Depot and done so in a simple, elegant and complimentary manner to the Union Depot. Here’s an off the cuff idea: enclose the concourse extending from the depot with glass, creating a beautiful glass hallway, and have the end of the concourse connect to a secondary building. There’s plenty of space available for such an addition. None the less, an addition may not even be necessary.

3) Environmental Control

Appropriately, the JMC Board is concerned about the presence of environmental control in the Union Depot. It seems that it would be a matter a fact element of any renovation of the Depot, particularly a restoration performed with a archival purpose in mind. In many ways, as photographs will often attest, the Depot is a blank canvas and now is the time where such improvements can be made and without the cost of tearing out existing material to replace it. (That former material has already been torn out!) Again the basement and the standing water. Here’s a simple answer: pump any water out, replace any water damage and effectively seal the basement walls. We’re not contractors here at Historic Joplin, but this solution does not seem to be one of great complication.

Mr. Shirley claims that the JMC board has not taken a position about the proposed move. We would disagree. No member of the board, or JMC Director Brad Belk, have not once said anything positive about the idea. In the summary, Mr. Shirley does note they support the preservation of the Depot, as we would hope of those who are charged with protecting the city’s history. However, supporting the saving of the Depot does by no means equate to supporting the idea of moving the museum. Fearfully, three members of the City Council appear ready to allow the Board to do as it wishes, which means doing absolutely nothing. The Board wanted Memorial Hall for a new home, turned down the offer by the Gryphon Building, and will have to be dragged into the Union Depot.

This is not the time for inaction. Joplin has embarked on a push of re-establishing itself as a city of beautiful buildings and one engaged not only with its past, but with an active present focused on its increasingly vibrant downtown. The relocation of the museum to the Union Depot would not only give more people a reason to visit downtown, but its better accessibility than the remote location by Schifferdecker Park would mean more would take the time to learn about the city’s glorious past.

The leadership of the city has proven itself innovative and bold by the successful and ongoing restoration downtown, we hope that the leadership does not back down at this important juncture. The City holds the purse strings of the JMC and if the Board of the JMC is not willing to play a part in the revitalization and the new beginning of Joplin in the 21st century, the City should tighten those strings. The Board of the JMC needs to accept that they will not always get what they want and assume a much more forward thinking position, lest they end up as dust covered exhibits they profess to preserve.