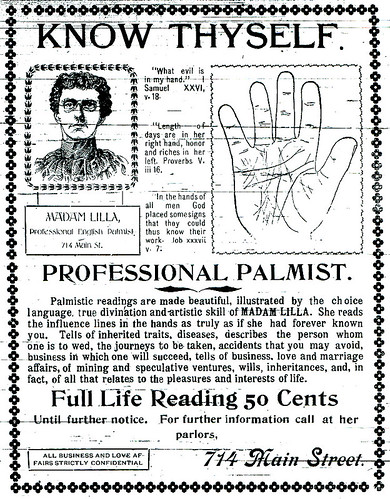

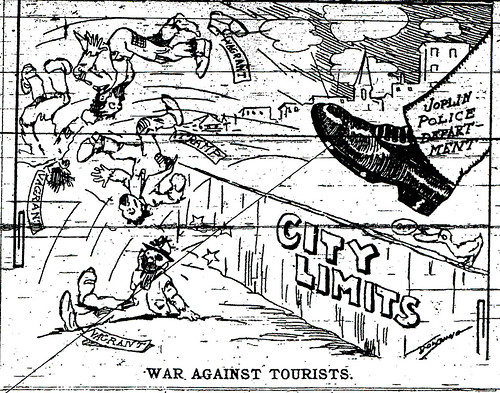

A few posts ago, we mentioned that Victorian Americans participated in palmistry, spiritualism, and séances. Throughout the years Joplin was home to numerous psychics, seers, and fortune tellers. An issue of the Joplin Morning Herald from 1895 announced, “Madame Zita LaRoux, the famous trance medium, may be consulted on all affairs of life for a short time only at 619 Joplin Street. She gives valuable advice on all subjects — love, marriage, divorce, lawsuits, business transactions, etc. Names and dates given.” But by 1913, the city fathers were tired of palmists, seers, and mediums, and subsequently prohibited them from practicing within city limits.

Unsurprisingly, clairvoyants and their followers were upset by the city council’s decision. Joplin City Attorney Grover James, who “took charge of an aggressive fight to drive from the city ‘seers’ and ‘mediums’ that have remained since the passage of an ordinance barring them from practicing in Joplin” received threatening letters. In one week’s time, James received half a dozen letters after his successful conviction of Mrs. T.J. Sheridan.

One letter read,

Mr. City Attorney,

City Hall

You think you are awful smart to prosecute a pore woman becauz she ain’t of your religion, doan’t you? Your talk at the trile was rite funny. Ha, ha. We’ll git you yet. Watch out.”

Another letter said,

Grover James

Joplin, Mo.

I write this to let you know that you may have misjudged the character of the people you are fighting. In persecuting worshipers you show an ignorance that is amazing. Many men have been shot for less than what you have done.”

Some people mailed Mr. James spiritualist publications while others stopped by his office to urge him to drop his campaign against fortune tellers and palmists. James, however, just smiled in response. He told the Joplin News-Herald, “I have found that many Joplin society girls attend séances and believe the stuff told them by mediums. When I started to gather evidence I supposed that I would have to obtain it from ignorant and superstitious persons. I found, however, that the elite of Joplin society are some of the best patrons of the mediums. Daughters of the most prominent Joplin citizens can tell me all I want to know about the ‘seers’ I am prosecuting. It may be that I will have half a dozen of the younger social set at the next fortune teller’s trial in police court.”

James confided he had gathered evidence against a local clairvoyant that “should be an eye opener to mining men that have the curtained rooms of mystics for their base of operations.”

According to James, “A woman ‘seer’ told a mining man just where to drill in order to strike ore. She said, however, that there was but one drill man that could find the stuff. She then described the man very closely. Half a dozen bids were made on the work. All of them were very low and reasonable but the mine operator was not satisfied. Finally a man came to him that fitted the woman’s description. His bid was thirty cents higher than any other but it was accepted.” The city attorney then claimed, “It has been shown that this drillman was kept in lucrative employment by the fortune teller who doubtless got a rakeoff for throwing him the work.”

Within a week, the “Reverend” Mary E. Anderson was arrested in Joplin for violating the clairvoyant ordinance. A few days prior to her arrest, Police Matron Vernie Goff visited Anderson in the psychic’s home at 731 Joplin Street and asked Anderson to read her fortune. Anderson informed Goff that she would first have to buy facial cream and then she would read Goff’s fortune. Goff complied. She purchased a tube of facial cream that normally cost nine cents in a drugstore from Anderson for one dollar. The purchase completed, Anderson read Goff’s fortune.

According the Joplin News-Herald, Goff learned many “interesting things about herself and family that she had never known.” Anderson claimed Goff had a long lost “Uncle Jim” and told her that her investments in an Arizona gold mine were a smart choice. The only problem was, according to Vernie Goff, is that she did not have an Uncle Jim, nor did she have any investments in gold mines.

Goff told the News-Herald that “the only money she has sunk in stocks was down on her father’s farm near Springfield, where she owns a little stock — that is some cows, calves, and such.”

At around the same time, two young boys had visited Mary Anderson and asked to have their fortunes read. She told them that her fee was one dollar. Unable to pay, the boys decided instead to testify against her in court. There was no need, however, as Police Matron Goff, Mrs. F.B. Cannon, and Miss Wathena Hamilton testified for the prosecution two weeks later. Like Goff, Cannon and Hamilton had both visited Anderson to have their fortunes read for one dollar. Anderson did not help her cause when she took to the stand, only to be caught “contradicting herself on many things.”

After a three hour trial, Mary Anderson was found guilty and fined one dollar and costs, as it was her first offense. She balked at paying the fine, but when told she would be taken to jail, Anderson borrowed a dollar from her attorney to pay the fine. She remarked, “I won’t have that News-Herald telling about me being behind the bars. I’ll pay the fine first.”

James’ campaign against palmists, mediums, and clairvoyants drove members of Joplin’s spiritualist community to Webb City. The News-Herald remarked, “One of the most notorious ‘seers’ of Joplin purchased property in Webb City and makes the city his home. He is doing a rushing business, it is understood.” But just as in Joplin, spiritualists were not welcome. The News-Herald reported that, “It was when a man came here from Columbus, Kan., for a ‘reading’ and became insane because of things told him by a ‘seer’ that Webb City businessmen began to wonder what became of the much talked of clairvoyant ordinance which was to have prohibited fortune telling in Webb City.”

Source: Joplin News-Herald, Joplin Morning Herald