Today many Americans, unless they live in an urban metropolitan center, have little interaction with the country’s rail system. Once in a while, one might find themselves stopped at a railroad crossing watching a train roll past, but gone are the days when the train would stop at the town depot to take on coal, passengers, mail, and freight before heading to its next destination. Peruse an old Joplin newspaper and ads from the St. Louis and San Francisco “Frisco” Railway touting summer excursions to Eureka Springs, St. Louis, and Chicago spring from the pages. Joplin was fortunate that it not only had an extensive interurban trolley system, but was home to a handful of rail lines that carried lead and zinc to industrial centers in the east.

With the trains came hoboes and tramps. Just a few years after the turn of the century, the Joplin Daily Globe reported that local train crews were having problems with hoboes. “According to trainmen,” the Globe recounted, “they are having more trouble with tramps this winter than for a great many years. They are of the worst class and are exceedingly dangerous customers. They are traveling around stealing rides when they can and endeavoring to find the most favorable places for looting stores or cracking safes.”

The trainmen claimed that the “harmless hoboes who would go out of their way rather than harm a human being are very much in the minority.” Instead, many trainmen told the Globe reporter that they had engaged in “hand to hand fights in an effort to rid the train of them.” Many of the fights broke out during the night when hoboes boldly roamed the rail yards in groups of four to six men.

Later that year, the Globe reported that the, “rail road yards have been especially infested with the merry willies of late.” Nels Milligan, a Joplin police officer detailed to keep an eye on the hoboes told a Globe reporter, “All up along the Kansas City Southern embankment from Broadway to Turkey Creek, you could see the bums lying stretched out in the warm afternoon air sunning themselves like alligators or mud turtles on a chilly afternoon, and here and there was a camp.” According to Milligan, a hobo’s camp consisted of a “small fire that you could spit on and put out, between two or three blackened rocks, and a blackened old tin can, and an improvised pan or skillet made out of another tin can melted apart and flattened out.”

Sometimes a hobo succeeded in getting a free meal.

The officer admitted there were too many hoboes and not enough room in the jail to house them. He worried they would be “working the residence district for grub, hand-outs, punk, pie, panhandle, pellets, and any old thing they can get together.” Once they had food, Milligan claimed, the hoboes would “feed and gorge and lie around there like fat bears dormant in the winter time” until a bout of bad weather would send them on their way.

Five years later, the Joplin News Herald interviewed a railroad employee about the tramps who traveled through Joplin. Watching a couple of hoboes jump off of a freight train in the Joplin rail yards, the railroad employee remarked, “See those fellows getting off up there? Now there is no telling where they got on, nor where they rode.” He shook his head. “There’s another thing connected with this hauling of tramps. Some of the most notorious criminals of the country have occupied places on the train and eluded the crew for hundreds of miles.” According to the man, rail workers made every effort to assist law enforcement officers in locating wanted criminals who might be catching a ride on the trains.

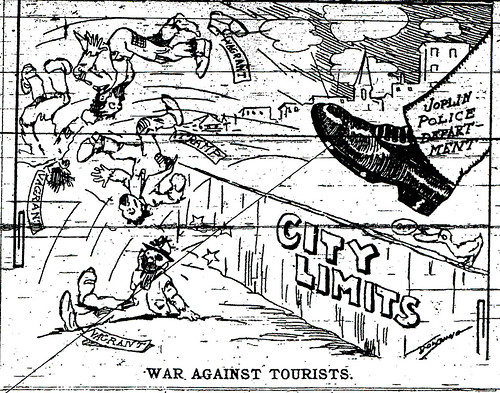

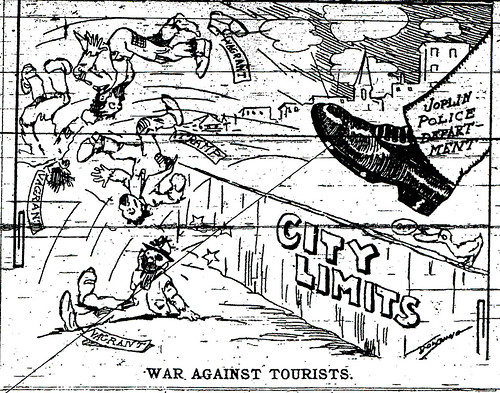

Joplin was still struggling with hoboes eleven years later when Chief of Police Joseph Myers directed his officers to sweep the town for any weary willies. Six men were arrested on charges of vagrancy, jailed, and then told to move on. But as long as there were trains rolling into Joplin, there were always tramps and hoboes to contend with.

Joplin Police kicking out bums and hobos

Hoboes were sometimes looked at in a humorous light. A hobo celebration was held at the “hobo cave one mile and a half north of the union depot in the hills of Turkey Creek. Twenty of the Ancient Sons of Leisure gathered there in the cool cave.” One of the hoboes stood up to deliver an impromptu address about the significance of the Fourth of July and said, “Fellow brothers, you all realize what this day means. It was on this day in 1776 that George Washington crossed the Delaware, whipped fifty thousand Redcoats and whacked out the Declaration of Independence. Since that time we have been independent. We do not have to work. I now propose a committee of three raid a [chicken] coop so we can have an elaborate dinner as befitting Washington’s birthday.”

By 1918, the day of the hobo in Joplin had begun to wane. Despite Joplin remaining an “oasis in the great American desert created by prohibition” it was no longer “possible for police to spread a drag net in the railroad yards and gather in anywhere from a dozen to fifty ‘Knights of the Open Road.’”

Tim Graney, a former Joplin police officer and station master at Union Depot, declared he had not seen more than half a dozen hoboes in the last year and not one in the past six months. The camps where the tramps and hoboes once gathered were empty. The Globe, unable to explain their absence, mused, “Maybe they have all gone to work…At any rate, they’re gone! The genus Hobo is no more!”

Sources: Joplin Globe, Joplin News Herald