Cycling was all the rage in the 1890s. Cycle tracks were built, races were held, and cycling associations were formed all across America. Cycling became an accepted form of transportation, rather than just a passing fancy. Today we might think of Mongooses, Schwinns, or Bianchis – brands that allow cyclists to ride across the country, over mountains, and commute to work on city streets. Bicycles in the 1890s, however, had heavy frames, cumbersome rubber tires, and uncomfortable seats. That did not deter a group of five friends from Joplin who hopped on their bicycles in the summer of 1896 and pedaled to Louisville, Kentucky.

Businessman Fred Lawder, attorney Arthur E. Spencer, Boone Jenkins, Captain Marion Staples, and “Ike” Simon left Joplin in August. Although they planned to pedal from Joplin to Louisville, they decided to ship their bicycles to St. Louis and then pedal to Louisville. They made the trip in four days with stops at Vincennes, Indiana, and Cincinnati, Ohio. They spent a considerable amount of time in Louisville before heading west on their bicycles, passing through much of Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, and Ohio. They returned to St. Louis where Simon and Spencer, citing pressing business concerns, caught a train back to Joplin. The remaining three men made the trip back to Joplin by bicycle.

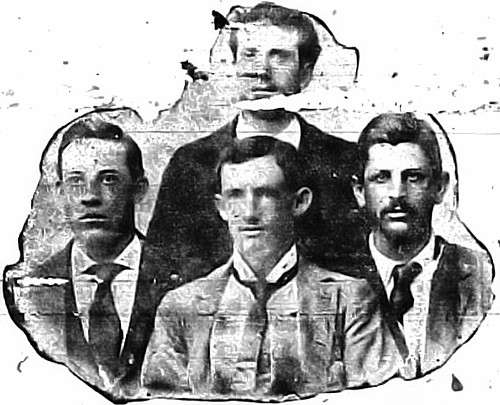

They became somewhat of a media sensation. It was recalled that “at every city in which stops were made the party was besieged by reporters, and newspapers published column after column regarding the tour, together with photographs of the tourists and their bicycles.”

The remaining three men returned to Joplin in September, but not before Captain Marion Staples appointed himself a missionary for presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, and preached the gospel of free silver to curious onlookers during the trip. Staples was a surprisingly spry fifty years of age when he made the trek. It was reported that while the other riders were young men, Staples “stood the trip as well if not better than his companions and reached home in better physical condition than he was when he left.” He lived to the ripe old age of 78.

Source: Joplin Daily Globe