As the snows continue to melt away and we can begin to envision warmer days and the return of leaves on trees, flowers on the ground, and birds from southern lands, we also have the return of the annual National History Day event. On March 4, students in Joplin will be participating in the event that will culminate in competition on the state level in Columbia in April.

To learn more about History Day, we contacted Dr. Paul Teverow, a professor of History at Missouri Southern State University since 1982, and the National History Day Coordinator for Missouri Region 6. Dr. Teverow was kind enough to answer some questions we had about the event.

Dr. Paul Teverow

Historic Joplin: What is National History Day?

Dr. Teverow: It is an academic program for students grades 8-12. Students present their research and analysis — in the form of papers, exhibits, performances, documentaries, or websites — on historical topics of their choosing related to the annual theme. The 2011 theme is “Debate and Diplomacy in History: Successes, Failures, Consequences.”

Historic Joplin: When did it come to Joplin?

Dr. Teverow: I believe 1979 was the first year at MSSU, where the Social Sciences Department has always sponsored the contest for this part of Missouri.

Historic Joplin: How did you become involved with History Day?

Dr. Teverow: When I came to MSSU in 1982, I joined colleagues in the Social Sciences Department who served as judges. In 1989, the Department Head asked if I would serve as contest coordinator. And that’s the way it’s been.

Historic Joplin: What has surprised you most about the students participating in National History Day?

Dr. Teverow: I am first of all surprised by the high quality of so many entries. Stories about education and student achievement today tend to focus on the low motivation and achievement of American youth. But in most of the entries, I see a depth of research not so common “in my day.” Some of them have found primary sources in archives & online that even judges familiar with the topic had not known about. On the few occasions when I have judged in recent years, I have also been impressed by quality of presentation in the exhibits, performances, and documentaries. Many students show a real talent for presenting their research in an engaging manner. If you saw the best of these entries in a museum or on PBS, you’d believe that they were created by professionals. Plus who would not be surprised to be an in auditorium full of 12-18 year olds who are genuinely excited to be participating in an academic contest?

Historic Joplin: We’ve had science fairs for decades, why do you think it took so long to have an event for history established?

Dr. Teverow: It’s true that History Day has not been around as long as Science Fair, but at 37 years [the first contest was in 1974], it’s hardly the new kid on the block. You’re right; it is still not as well known as Science Fair, but each year, about 500,000 students nationwide participate. That’s not chopped liver!

Historic Joplin: What are the benefits of History Day for students? For teachers?

Dr. Teverow: First and foremost, History Day gets students excited about history. Researching a History Day project has to be among the best way for students to learn that history matters: that events in the past have shaped their world; that what people choose to do and how they choose to do it have consequences; that for almost everything they take for granted, the past presents alternatives, some disastrous, some surprisingly viable. I have also had several History Day alumni and their parents tell me that History Day played a very valuable role in preparing them for college, because in the course of creating a History Day entry, they develop:

â— critical thinking and problem-solving skills

â— research and reading skills

â— oral and written communication and presentation skills

Teachers also testify to the educational benefits. They have shared with me examples of how History Day motivates students and brings out hitherto hidden talents.

Historic Joplin: Is participation growing every year?

Dr. Teverow: During my almost 30-year involvement, it has fluctuated quite a bit, with about 200 total entries in a “normal” year. This year, because many schools are cutting back on anything that requires transportation off-campus, I expect participation to be down a bit.

Historic Joplin: Do students cover Joplin/Southwest Missouri personalities and topics? Have any stuck out in your mind as memorable?

Dr. Teverow: So long as it can be connected with the annual theme, ANY topic in world, US, or local history is fair game. I do find that for some students, a topic with a local connection makes history seem more immediate. It may also lead them to unusual primary sources and help them better understand how historians use primary sources to reconstruct the past. Of course, with entries on local history, it is especially important to place the developments in the context of broader developments during the period in question. Here is a sampling of award-winning entries from the past few years with local connections:

2006 Sarah Mouton, Carthage High School, Carthage, Teacher/s: Caroline Tubbs; A Talking Campaign: Emily Newell Blair Takes a Stand for Social Justice and Political Equality.

2007 CORY BAKER, SARCOXIE HS Teacher(s): DIANNE ELLIOTT

Entry Title: RIPE FOR THE PICKING: THE STORY OF SOUTHWEST MISSOURI

2008 JENNIE SNYDER CARTHAGE JUNIOR HIGH Teacher(s): KATHLEEN SWIFT/SUE PITTS Entry Title: COMPROMISING A LIFE: NANCY CRUZAN’S CONFLICT IN DEATH

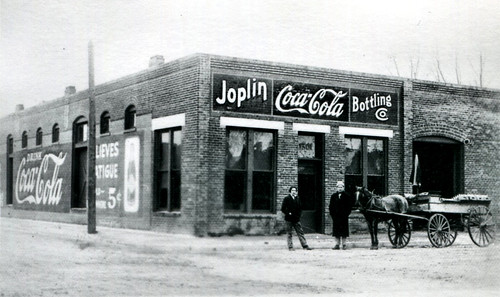

2009 Julia Lewis Annie Baxter: Woman, Wife, and County Clerk Annie Baxter: Woman, Wife, and County Clerk Joplin, MO, Joplin High School, Andy

2010 Eric Peer, Hoisting Joplin to Fame: The Freeman Hoist

Carthage, MO, Home School TEACHER(s) Julie Peer

Historic Joplin: How can individuals who aren’t teachers and students be involved? Can people donate money to support National History Day?

Dr. Teverow: I’m always on the lookout for judges. History Day could not work without qualified judges. In the end, what most students take away from History Day is feedback from the judges. Having someone show an interest in the project they have put hours into researching and developing, being able to be the expert when someone asks them questions, hearing and reading praise for what they have done right and constructive comments on what could have made the project even better — all of these things make students feel that their efforts were worthwhile and keep students coming back. Over the years, I have been fortunate to have a great corps of judges. They include my colleagues in the Social Sciences Department, MSSU faculty from several other departments, professionals from area museums and archives, retired teachers, and people in various walks of life with a love of history.

Yes, national History Day welcomes donations. See http://nhd.org/WhySupport.htm I am embarrassed to say that until I read your question, I had not thought of establishing a special History Day fund at MSSU, but I will definitely look into it.

Thank you for your time and answers, Dr. Teverow!

In addition to the information provided to us by Dr. Teverow, an independent evaluation of the program just released findings that support the benefit of National History Day to students. The evaluation discovered that students who participated in National History Day performed better on standardized tests than non-participating students, and not just in history, but other subjects like mathematics, reading and science.

Understandably, History Day is something we can definitely get behind here at Historic Joplin! For information on National History Day, just click on this link.