On a rainy spring night in 1878, Marshal L.C. Hamilton turned to a reporter from the Joplin Daily Herald and proclaimed, “If you want to see Joplin by gaslight, take a trip with me.” Not one to pass up a promising story, the reporter stepped under the officer’s umbrella, and together the two men set out into the darkness. “I’m going to raid the brothels,” Marshal Hamilton declared, “Many of the inmates are behind with fines and complaints are being made.” Together the two men visited several brothels over the course of the night, most of them “so filthy” that the Marshal and the reporter chose to stand outside on the steps, rather than go inside.

Despite the efforts of the “city dads” and the police, Joplin’s streets and sidewalks remained populated by prostitutes for years to come. In 1902, Josie Seber was arrested by Office Meanor for streetwalking. She pled not guilty to no avail. Judge Walden fined Josie ten dollars for streetwalking, but the jury decided the fine was too low and pushed the fine up to fifty dollars. Her counterpart, Etta Pitts, was fortunate in that she was only fined ten dollars, but because she was unable to pay the fine, was returned to her jail cell.

As Joplin Police Matron Ellen Ayers would find out, many of Joplin’s prostitutes were addicted to cocaine, morphine, and alcohol. Flo Banks reportedly had a “police record as long as any woman in the city” but in 1902 she declared, “her intention of being good henceforth and forever.” A Globe reporter noted Flo was a longtime “cocaine fiend” but that soiled dove had sworn she had given up her addiction once and for all.

Prostitution was also a family affair for Flo Banks. She and her sister, Pearl Banks, ran a brothel at 629 and 631 Pearl Streets in Joplin. Although it was repeatedly raided by the Joplin police, Flo and Pearl continued their life of crime. The rewards were simply greater than the risks.

Not all scarlet women came from impoverished backgrounds. Gertrude Rhodes, who was arrested by Officer Theodore Leslie and Officer Ben May for “beastly intoxication” claimed she was from a well-to-do Kalamazoo, Michigan, family. She had married a man whose “weakness was poverty.” They moved to Pittsburg, Kansas, and although her husband idolized her, she grew restless and angry at their poverty. Seeking an escape from her husband and young child, Gertrude Rhodes left her family and headed to Joplin, and within a few days “became scarlet.” After spending time in the Joplin city jail, Gertrude announced her intentions to return to her parents in Kalamazoo. If she returned to Kalamazoo, only her parents know.

Other girls were more fortunate. Pearl Bobbett left home to travel to Pittsburg, Kansas, after she was promised a job. Upon her arrival, she found that the job required her to dance in a “hooche-kooche” show. Pearl told a Globe reporter, “I had no money or I should have come home at once. I only had $2 when I started. Afterwards they wouldn’t let me leave.” Joplin Police Officer Cy Chapman, who was dispatched to Pittsburg to escort the girl back home, “had to resort to force to get her away from” the show’s managers but not before she had been hit by the showmen with a stick on her neck, arms, and back.

But many ended up like Annie “Black Annie” Stonewalk, an African-American prostitute in neighboring Galena, Kansas. Annie, who was arrested in early 1902 for disturbing the peace after a fight with fellow white prostitute Jose McClure, died a few years later in 1904. It was at the home of Mrs. James Burton, where the former street walker succumbed to a slow and painful death from consumption. The Joplin News Herald remarked, “She has been giving the officers much trouble since she arrived in Cherokee County four years ago from Alabama. Her life would have been shortened months sooner if it had not been for Mrs. Burton’s kindness.”

By no means sanctioned, prostitution existed outside the law but for occasional attempts to reign in its excesses. Of the women who by intent or by desperation were drawn into the trade, little is known except when apprehended by the police or sought out by reporters who sought shocking or pitiful stories to draw in readers. Never the less, any history of Joplin is incomplete without acknowledging their presence and their impact upon the city that Jack built.

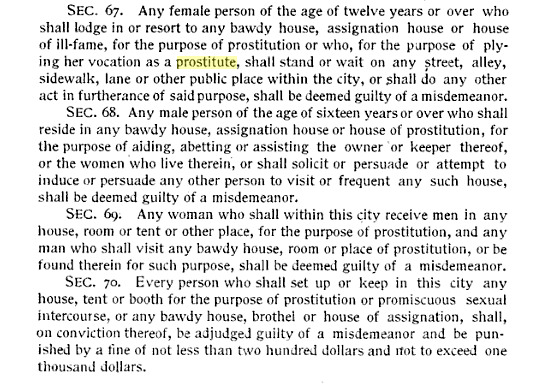

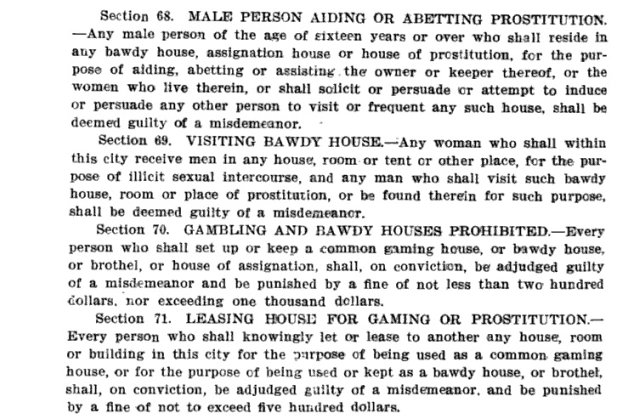

Sources: Joplin News Herald, Joplin Globe, Joplin ordinances.