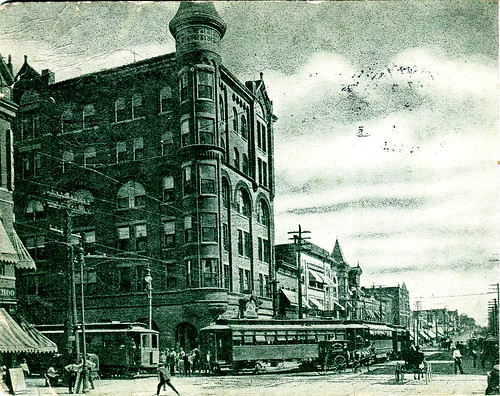

Under a bright October afternoon sun, a crowd of ten thousand gathered to watch a parade snake its way from Fourth and Joplin streets to Main Street. It turned under the watchful gaze of the Keystone Hotel and then proceed south to Ninth, where it turned again to the right and came to a stop at Ninth and Wall. It was October 8th, and the people of Joplin had come to celebrate the laying of the cornerstone of the new Carnegie Library.

The parade had formed at 2:30 pm and consisted of a number of different groups. In the vanguard was Police Chief Jake Cofer with a platoon of police officers. Behind the police, the South Joplin band played and stomped in celebration, and were followed by 66 members of the Knights Templar from Joplin and the surrounding area. The contingent of Knights Templar was outnumbered by the 151 members of the Masonic Blue Lodge. Behind the Masons came 2,386 excited school children, headed by 29 high school students and teachers, walked four abreast down the city streets.

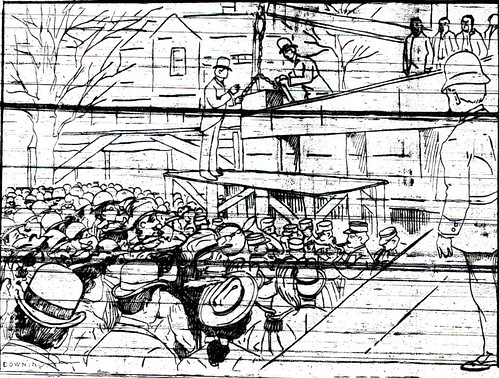

A different parade, but an example of a parade down Main Street and how the Elks might have marched that October afternoon.

Behind the flood of children came 24 grey headed members of the Grand Army of the Republic from Joplin’s O.P. Morton Post. As in 1865, the veterans marched proudly behind a cherished battle flag. Approximately 60 individuals of the Elks and Eagles followed the veterans and then bringing up the rear were thirty members of the Knights of Pythias commanded by Joplin attorney Joel T. Livingston.

Thousands surrounded the construction site of the library. The limestone walls soared over the crowd, such was the progress that had been made since Augustus C. Michaelis was selected as the architect in February. A platform rested against the side of the building next to where the cornerstone was to be laid. Children, anxious to see the ceremony, climbed the surrounding trees and hung perilously from branches.

A band took up position beside the platform while the mayor of Joplin, John C. Trigg, climbed onto the platform to address the crowd. His speech, the lengthiest of the day, began with the origin of the movement for the library. The mayor boasted that the tax revenue from property valued at $4,000,000 was more than sufficient to support the library, but also noted that it had not been enough for the construction of the building. For this, Mayor Trigg credited industrialist Andrew Carnegie who, “came to the rescue and dissipated all doubts and disquieting fears.” Trigg continued:

“No event in the history of the city of Joplin will perhaps stand out in bolder or more prominent relief in the future than the laying of the corner stone of the Carnegie public library building…It should be accentuated as a distinct epoch in the annals of the city, from which to date as from the dawn of the new century, an augmented zeal in the material, moral and intellectual improvement of our people of all classes and conditions…”

After the mayor established the effect of the library on the city, he then described the benefit of books, “The inestimable value of books is no longer a vexed or mooted question. The wise, the good and the great of all ages and nations, divines, poets, philosophers and statesmen, have contributed the most cogent and convincing testimony in support of the premise.” Trigg went on, reading excerpts from such authors as Joseph Addison, Richard DeBury, and Louisa May Alcott. Finally, and perhaps to the relief of some in the crowd, the mayor concluded his speech. This was followed by a brief rendition of the song, “Remember Now Thy Creator,” that setup the next speaker, Reverend Paul Brown. Brown was a substitute for Judge Picher, who had been unable to attend the ceremonies that day.

Reverend Brown reflected on the origin of free libraries and then spoke of libraries as essential to democracy:

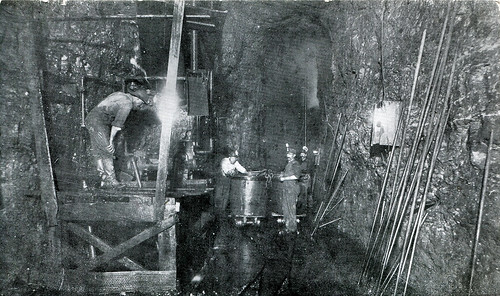

“What is the end of democracy? I answer the end of democracy is a natural aristocracy. There is an aristocracy of nature which no contract or statute can ever abolish….Here in the district, our chief industry, mining, weeds out weaklings and cowards, and creates a natural aristocracy of physical courage and vision in the depths of the earth. Now what does democracy guard against? Not natural aristocracy, but artificial, the aristocracy of mere birth or place or force or accident. Democracy means that equality of opportunity which will give the natural aristocracy a chance.”

It was books, Brown argued, that provided the opportunity for men to overcome the privileged aristocracy who were born to fame, title, or fortune. Brown, after noting famous authors of history, praised the city’s superintendent, J.D. Elliff, whom Brown stated, had played the crucial role in seeing the library created. Brown soon concluded his remarks, followed by a song from the band, and again, when the time finally came for the actual laying of the cornerstone.

This august moment was overseen by the Most Worshipful Grand Master of the Masons, John C. Yocum. The Grand Master announced the placement of the cornerstone, as it was guided by a small crane and lowered carefully into place. An invocation was given by the Mason’s Grand Chaplain, who was accompanied by the Masonic ceremonies of deposit and consecration. One last speaker arose, Dr. W.P. Kuhn, a senior grand warden of the Masons from Kansas City. Dr. Kuhn opted to win the crowd through praise of the children present, as well a quick joke about Methodist and Presbyterian preachers:

“ The Methodist preacher never prepared a sermon or at any rate never had any reference notes, but his services were largely attended, while the Presbyterian divine labored conscientiously over his discourses, wrote them painstakingly out and read them with painstaking fidelity. But, his flock was few, and in a spirit of discouragement he came to the Methodist preacher and asked him why it was that the people crowded to hear him who never prepared a sermon while his own church was all but empty. And the Methodist replied, “My good friend, you write out your sermons and the devil is right there behind you. He knows every word that you’re going to say and he is able to circumvent every effort you make, no matter how praiseworthy. Now I don’t know what I’m going to say and I know the devil don’t know what I’m going to say either, and that’s the difference between us.”

Dr. Kuhn concluded by stressing the importance of free libraries, as they were part of the “three planks that the structure of every American community is founded.” The other two planks were free thought and free speech. Immediately after the crowd sang, “America,” and the cornerstone laying ceremony ended with a benediction offered by the Rev. Charles A. Wood.

With the cornerstone laid, construction on the library resumed. The building incomplete, the actual Joplin library, which was already in existence was housed at the Joplin high school and overseen by Lucile Baker, the first librarian. Ms. Baker was a writer for the Joplin News-Herald and used the byline of “Becky Sharp” in a nod to Missouri’s own Mark Twain.

The library was finally completed a year later. The city received its first check from Andrew Carnegie at a sum of $5,000. Twelve years later, the city sought and received another $20,000 from the generous benefactor for an addition to the west side of the library. In charge of the library, now at home in its new building, was Mary B. Swanwick, who was joined by assistant librarians Blanche Trigg, Mary Scott, and Hattie Ruddy Rice.

As of 1911, the library had 15,737 books as well as 2,643 magazines and periodicals. Over the year, over ten thousand people used the library, around 1/4th of the city’s population, and almost 65,000 books were circulated. Active card holders numbered almost 7,000. Ten years later, the head librarian, Swanwick, passed away and was eventually replaced by Blanche Trigg, daughter of Joplin Mayor John Trigg. She oversaw the institution until 1949. It was under the oversight of Trigg’s successor, Margaret Hager, who helped lead the movement in the 1970s to purchase the Connor Hotel and the rest of the 300 Block as the site of a new library building. That building, the present home of the Joplin Public Library, opened in April, 1981.

Sources: Joplin News Herald, Joplin Globe, “A History of Jasper County, Missouri and its People,” by Joel Livingston, and Missouri Digital History.