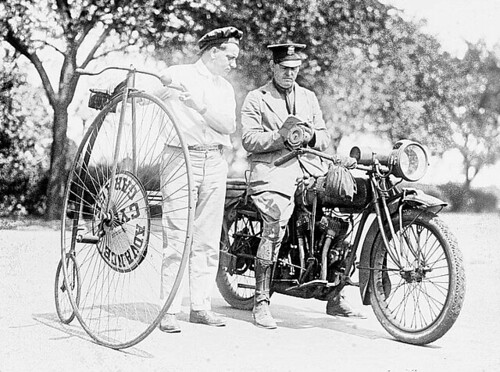

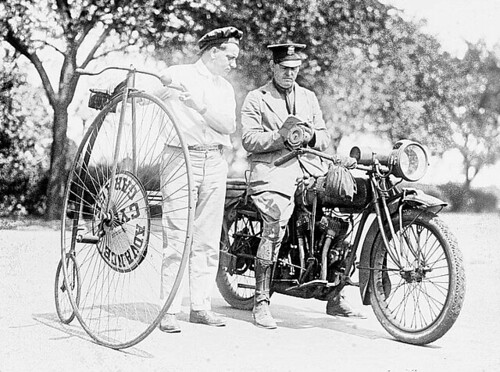

An example of a motorcycle patrolman from around 1922 via Library of Congress

At approximately 5:45 pm on a Monday in June, Roscoe Barbee, son of the wealthy and influential Gilbert Barbee, drove quickly north on Joplin Street in his Speedwell touring car. His speed reportedly between 30 and 45 miles per hour, Barbee passed over 6th Street and headed for 5th under the late afternoon sun. At the same time, a horse drawn buggy slowly made its way west along 5th Street. Its occupants were four young women, Mary Delaney, 19 years of age and a stenographer at the Rudd Insurance company, was accompanied by her guest, Minnie Sanford from nearby Jasper, and the 20 year old twin Shigley sisters, Ruth and Blanche. Ruth worked as a bookkeeper for the Thomas Fruit Company and her sister, a stenographer like Delaney, worked at the Walker Insurance Company.

The collision occurred as the four women turned their buggy into a right hand turn to proceed north up Joplin and as Barbee turned left to go east on 5th Street. The touring car clipped the wheel of the buggy, which sent its occupants into the air, while Barbee skidded to a stop some distance down 5th Street. The witnesses were many, one being deputy constable Fred Gault, who raced down 5th Street to arrest Barbee. A city prosecutor, W.N. Andrews, volunteered himself as a witness.

The women were found lying on the street paved with bricks. Blanche Shigley and Minnie Sanford, though stunned, suffered only bruises. Ruth Shigley and Mary Delaney, however, were seriously injured. Witnesses quickly reached the women and carried them in out of the summer heat and into nearby homes and buildings. Mary, described as having sustained a skull fracture and “her face disfigured,” was carried into the home of J.M. Ryall, at 420 Joplin Street, where Mrs. Ryall, who knew Delaney, failed to recognize due to the extent of her injuries. Such were the severity, that Delaney’s identity was at first hard to establish.

Ruth Shigley, was also horribly mangled, having sustained injuries to her head and internally. Unconscious, she was carried into the lobby of the Lyric Theater, where her less seriously injured sister Blanche had previously been taken. From there, an ambulance from the J.M. Myall Undertaking Company transported her to St. John’s Hospital. The News Herald reported, “her clothing was bespattered with blood and her features were not recognizable by those who crowded about her.”

Roscoe Barbee was unhurt and by 7pm, just under an hour and a half later, had been arraigned for one charge of feloniously maiming to Mary Delaney, and then an hour later, received a second charge for gross negligence and causing the injuries to the Shigley sisters. A preliminary hearing was set for Saturday, and Barbee was quickly bonded out of jail for $7,500 courtesy Dan F. Dugan.

By Wednesday, doctors at St. John’s, believed that both women had a fair chance at recovery despite the fact that neither of them had regained consciousness. Further details were offered toward the women’s injuries, with doctors unable to discern if Mary Delaney had suffered any skull fractures, but had sustained a crushed cheek bone. Ruth Shigley, had suffered several fractures of the skull and doctors were forced to act to relieve the pressure that built behind the injuries. That morning, Ruth had emerged from unconsciousness only briefly, before she had slipped back out. Of the other two women, Ruth’s sister, Blanche, and Minnie Sanford, they were described as suffering from a nervous shock, but were otherwise unharmed. Barbee, meanwhile, refused to offer comment about the accident.

The talk not dedicated to the state of the girls on Wednesday was devoted to the pressing need for a motorcycle for the Joplin Police Department. Motorcycles were not yet commonly found in police departments at the time, but a great amount of frustration revolved around the failure of motorist to abide by the city’s speed limits and the police department’s ability to capture and punish those violators. The speed limit in Joplin at the time was eight miles per hour. As previously noted, witnesses believed that Barbee had been traveling at a rate between 30 to 45 miles per hour.

Assistant Police Chief Ed Portley was eager to comment on the need of a motorcycle for the department, “The police need a motorcycle.” Portley continued, “We are doing our utmost to arrest all person who are guilty of violating the speed law, but when there is no evidence obtained except that furnished by pedestrians or others who have no means of rapid riding, it is hard to convict the guilty.” Portley pointed out that with a motorcycle, “whenever a machine was seen speeding the patrolman could follow, gain all the evidence necessary and a conviction would follow, in all probability.” The assistant police chief went on to note that the presence of the motorcycle patrolman would likely greatly decrease the number of speeding vehicles and if the city council would not pay for a motorcycle, the department would find a way to procure one.

Future Mayor Taylor Snapp also weighed in on the issue through his position as president of the Joplin Automobile club. Snapp quickly noted that speeders would not be defended by the club, more so, that the club would do everything it could to assist the police. Snapp offered, “If necessary the club will furnish a special automobile for the purpose.” Though, Snapp agreed, “I think the city should employ a motorcycle policeman to look after unruly auto drivers.” The president of the auto club also raised the issue of speed limits and pointed out that the state’s speed law conflicted with the Joplin speed law in residential areas, with Joplin’s law being a lower speed. Furthermore, most automobiles had a hard time keeping to such low speeds in their high gear and that existing conditions should dictate the speed that a car might go, regardless of the neighborhood. He added, “a great speed should not be attained within the city limits, no matter how clear the streets may be…”

While the debate continued, the condition of Ruth Shigley finally began to improve, while Mary Delaney not nearly as much. While Roscoe Barbee’s lawyer argued that none of the charges were applicable to his client with the exception of possibly a misdemeanor charge of fast driving, Mary Delaney continued to slip in and out of consciousness.

At this point, the newspaper coverage of the affairs of Roscoe Barbee and the condition of Ruth Shigley and Mary Delaney falls from the front page coverage it had enjoyed. The conclusion to their stories remain to be discovered and reported. One result can be reported. In the first week of June, 1911, Mayor Osborne offered a commission to Joplin’s first motorcycle patrolman, J.C. Haus. While the make and model of the patrolman’s motorcycle was not provided other than it being “the best and fastest” available, it was boasted that the machine could reach 60 miles per hour and possibly faster. Two more machines were to be ordered for the constabulary force.

The procedure for enforcing the speed limit was simply for the patrolman to catch up to the speeding vehicle, note his speed, as it would be the same as the violator’s, and write down the motor vehicle’s number, and then report the matter to “proper officers.” A register existed which cross-referenced the vehicle number and the owner, and by checking against this register, the owner could be summoned to court to pay for his or her speeding crime. As a tangent matter, efforts were to be made to insure that all cars displayed their numbers properly and had lights.

Thus, from an accident at the intersection of 5th and Joplin Streets, Joplin came to acquire its first motorcycle for the police force. The force still retains motorcycles today, as late as 2007, when the department received two Harley Davidson motorcycles as a gift from a local Harley Davidson dealer. From 1911 to today, the Joplin Police Department has been employing motorcycle patrolmen for nearly a century.

Sources: Joplin News Herald