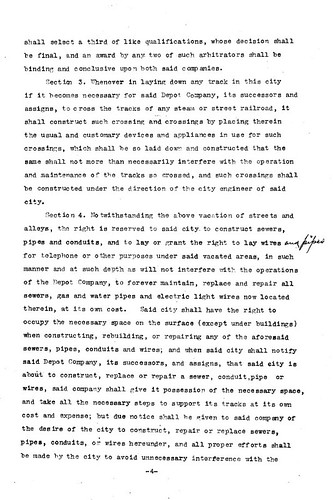

Our first installment of a history of the Joplin Union Depot covered the contentious debate between those for and against a franchise agreement offered by the Joplin Union Depot Company. Now we return to Mayor Jesse Osborne’s approval of the franchise and the long wait between approval and the start of construction.

On October 26, 1908, Mayor Osborne signed the franchise agreement after the City Council passed it with nearly a unanimous vote. Osborne’s approval was definitely made more likely when City Engineer J.B. Hodgdon returned from a trip to Kansas City two days before with a contract signed by the president of the Kansas City Southern, J.A. Edson, promising to supply material for 324 feet of a viaduct. As the Joplin Daily Globe noted, a viaduct was “Joplin’s dream,” for it would connect East Joplin with West Joplin. Despite the union of the two towns of Murphysburg and Joplin into one town over thirty years before, there still existed a recognizable separation of the neighborhoods that lay on the west side of the Kansas City Bottoms and those which resided on the east side. The viaduct would help erase these separate identities. Thus, the assistance of the Kansas City Southern provided a great impetus for Osborne to sign the franchise agreement.

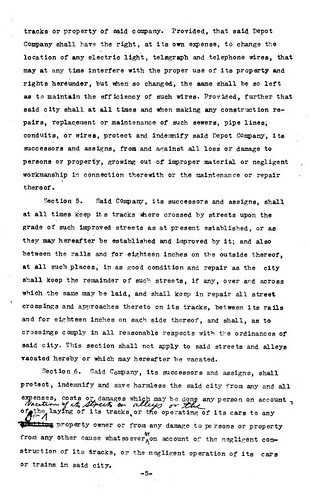

Guy Humes, later mayor of Joplin, but fierce opponent to the depot franchise passed by the City Council.

After the council had voted, but before Osborne had signed, the Joplin News Herald, one of the opponents to the franchise, went so far as to dedicate multiple columns to local attorney, Arthur E. Spencer, who claimed that the reaction of the Commercial Club (also an opponent to the franchise) was a reasonable one. Among the arguments Spencer relied upon was an existing franchise agreement which did not have such a contested “reasonable facilities” clause. (See our prior post for more information on that clause). For all the noise that the opponents of the franchise created, it was not enough.

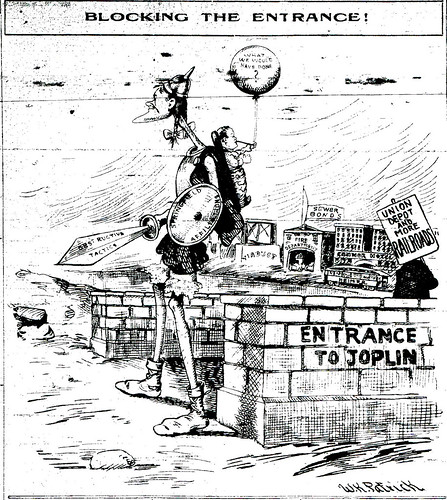

“Every such accession makes for bigger values within the city of today, and makes for a bigger city of tomorrow,” stated Mayor Osborne upon signing the franchise. The signing occurred despite a planned mass rally by Clay Gregory, the secretary of the Commercial Club. The rally, reported the Globe, was called off when Gregory was chastised by two other members of the club. It was the end of the opposition to the depot franchise. What followed may be construed as a big wait.

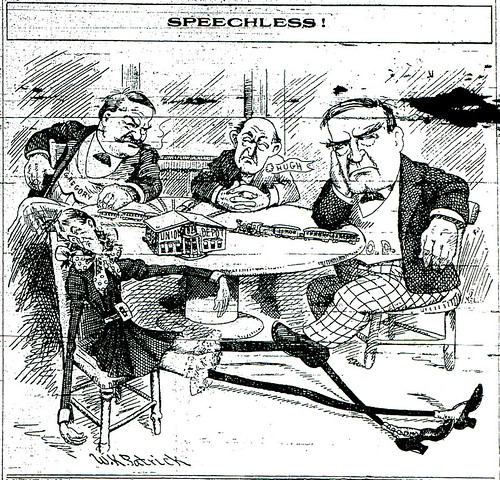

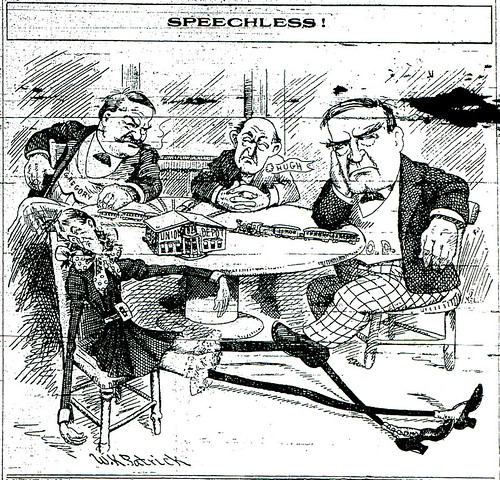

This Joplin Globe article noted the exasperation that many felt with the opposition to the depot franchise, including that from the much maligned Clay Gregory, Secretary of the Commercial Club.

News of the Union Depot virtually fell out of the headlines of both Joplin newspapers until a front page headline nearly five months after Osborne’s approval of the franchise. “WILL BEGIN WORK UPON UNION DEPOT WITHIN 30 DAYS, DECLARES EDSON,” announced the Globe. The news came from Gilbert Barbee, a Democratic political power in Joplin, as well editor and owner of the Joplin Globe, who had traveled to Kansas City and claimed to have spoken with the Kansas City Southern president, Edson. The claim initiated a brief spat between the Globe and the News Herald, which immediately set out to prove its rival wrong.

An editorial, published in the Globe, on April 4, 1909, summed up the dispute, which involved the News Herald sending its city editor to Kansas City to find contrary evidence to the news brought by Barbee. The Globe then charged that the News Herald was and had remained opposed to the Union Depot for two damning reasons. The first, that the newspaper wanted to “get on the roll” of James Campbell, whom the Globe labeled Joplin’s largest landowner and perhaps, Missouri’s richest man (and a large shareholder of the St. Louis & San Francisco “Frisco” Railroad). Campbell had been labeled an opponent to the Union Depot project because he wanted to establish a new Frisco depot, which would be in competition with the other depot. The second charge was that the individual who controlled the News Herald, unnamed by the Globe, but perhaps P.E. Burton, was actually a resident of Springfield and purposely used the “evening paper” as a means to vocalize against any improvement to Joplin. More so then than today, Springfield and Joplin were rivals, each competing to become the larger metropolis in Southwest Missouri. It was not beyond the vitriol of either populace to accuse the other of undermining their interests.

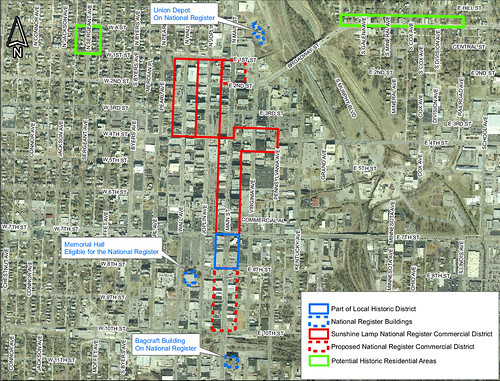

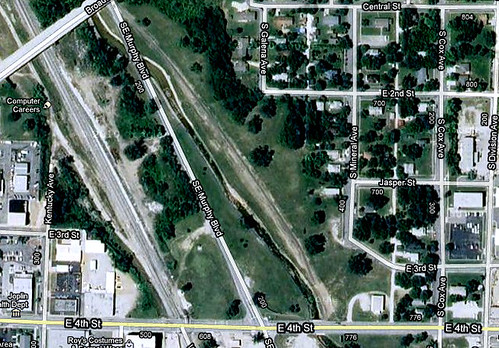

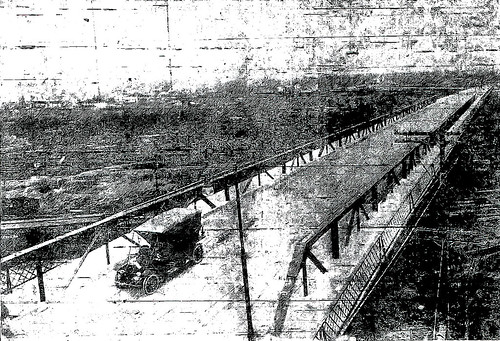

For all that the Globe had knocked its competitor for trying to undermine its claim, construction of the actual depot was still very far off. However, preliminary work to prepare the Kansas City Bottoms was underway by late April. One of the tasks deemed essential to a successful construction was the taming of the branch of the Joplin Creek which ran back and forth along the Bottoms. The creek, one of the barriers that separated the east and west parts of the town, had a reputation for flooding the Bottoms after intense rains. A representative from the Kansas City Southern was assigned the task of getting the permission of those who owned land (not owned by the Union Depot company) upon which the creek ran to change its course. The plan was to straighten the creek along the bluff near Main Street. By the time the representative departed, permission had been secured. As a trip to the former Kansas City Bottoms today will attest, the plan was well carried out.

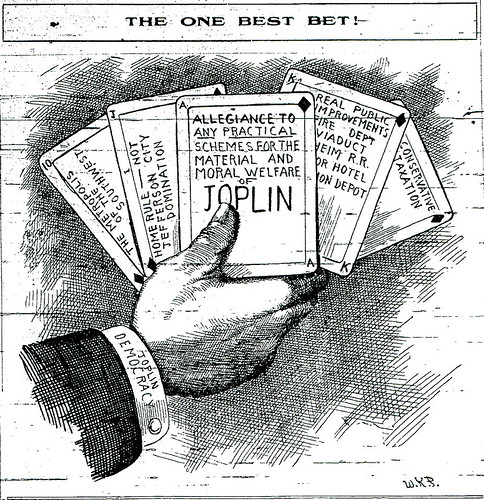

It was a belief, at least of the editors of the Joplin Globe, that Springfield actively sought to keep its rival Joplin from benefiting from any improvement which might make it more of a competitor.

The anticipation continued, however, as Joplin awaited news of the start of construction. In May, 1909, former Missouri governor, David R. Francis, an investor in the depot, along with other investors, visited Joplin. The former governor reassured the locals, and commented, “Plans for the depot are well in hand and arrangements are practically completed for work to begin soon.” News on the depot, however, was scarce until August, when it was announced that the Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railroad, also known as the “Katy,” had agreed to join the Union Depot company. This brought the number of railroads affiliated through the company to four: Kansas City Southern, Santa Fe, and Missouri & Northern Arkansas railroads, in addition to the Katy.

Additional news was the appropriation by the company of $200,000 for the construction of the station. The appropriation came as engineers from the Kansas City Southern, directed by William H. Bush, completed surveys of the depot and station site. The depot, Bush stated, was planned to be located near Broadway and Main, “situated 200 feet east of Main Street and the south line 150 feet north of Broadway.” When quizzed on the status of the depot, Bush confirmed that the plans and specifications were completed, as well the architectural plans drawn up. In a short time, assured Bush, the company would begin accepting bids from contractors. As part of the preparation process, the Kansas City Bottoms would be filled in to make a proper rail yard. As the engineer departed, it seemed that the building of the depot was not far behind. Indeed, not long after, on August 17, engineers from the Katy railroad arrived to survey a spur that would take their railroad to the future depot.

Despite the build up, developments of the depot again drifted out of the newspapers. In October, a fifth railroad, the Missouri Pacific railroad, expressed interest in joining the Union Depot company. Then, for the next three months, news about the depot, its impending construction, vanished from the headlines.

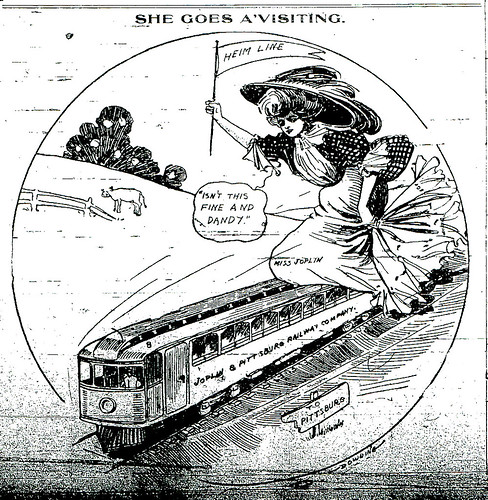

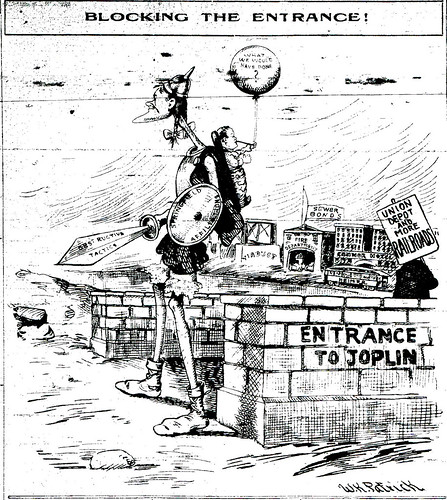

The citizens of Joplin, as the months passed, grew anxious for news about their expected Union Depot, as depicted in this Joplin Globe cartoon.

The silence broke on the first day of February, with the News Herald taking its turn to offer a reported start time from a traveler to Kansas City. The news came from a former Joplin resident, H.H. Haven, who passed on “reliable information” that work would begin soon. The paper, which noted the long wait by beginning its article, “After months of inactivity…,” brought forward the news that the cost of the depot construction had grown to anywhere from half a million to 700,000 dollars. The station, itself, the paper noted was still expected to be about $40,000. This figure was quickly upended by a report a few days later, based on information from the city engineer, Hodgdon, who was being tasked with overseeing the depot construction.

Hodgdon, in early February, was tasked with completing more survey work, specifically for the station itself. The reported plans he worked from described a station that at some points was three stories high. More incredibly, the estimated cost of the station had more than tripled to $150,000. In terms of immediate work, the city engineer expected that a great number of men would be hired to grade the Kansas City Bottoms, filling in places that needed filling in, and other places required lowing. A retaining wall was expected for the area near Main Street, as well. In all, Hodgdon explained to a News Herald reporter, “there remains a big amount of engineering work to be accomplished before actual work on the station can commence.”

“$750,000 OF UNION DEPOT BONDS ARE SOLD,” loudly announced the Daily Globe, on February 12. The bonds, issued at thirty-five years and 4.5% gold backed bond, had been sold to the George C. White, Jr. & Co., located in New York, as well the Pennsylvania Trust, Sate Deposit and Insurance Company. Of the $750,000, $500,000 was to be put to immediate use in the construction of the depot. The Globe also raised the figure for the station upward again to $280,000 and noted that plans for the station were complete. The paper described the station as such, “the building proper will be constructed from brick and that it will contain ample waiting rooms, adequate facilities for handling baggage, railroad and other offices.”

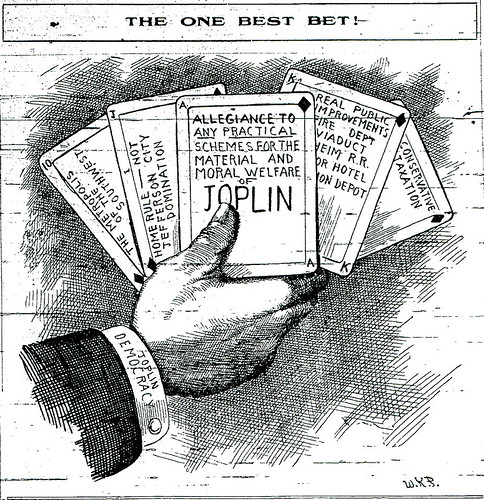

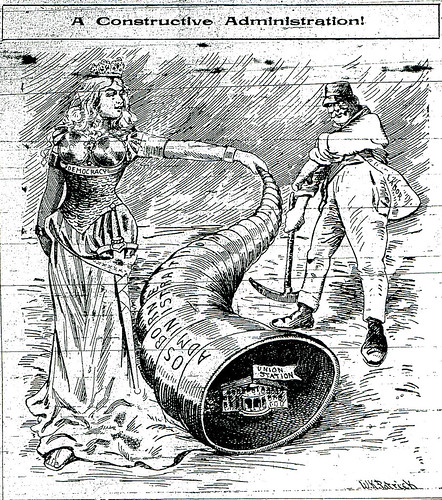

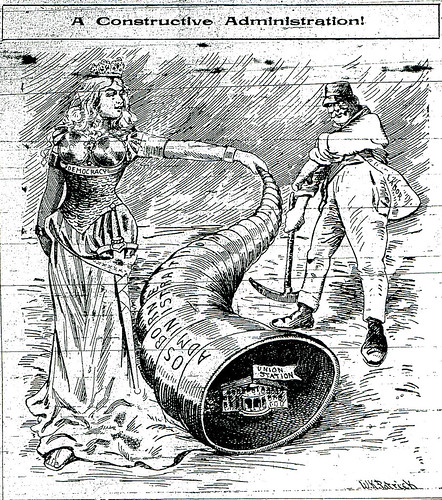

The signing of the depot franchise was considered a major victory for the administration of Mayor Jesse Osborne. Furthermore, it was viewed as victory for democracy. Note that Joplin here, unlike other political cartoons, is depicted as a miner.

Perhaps the most accurate timeline yet for depot construction was presented with the grading alone, which was to cost at least $50,000, to take at least eight months to complete. The magnitude of the grading problem was made evident with the expectation that in some places, depths of as much six feet would need to be filled in. Again, the overall cost of the depot was raised, now to an estimated million dollars. The actual station and train sheds were expected to be finished by January 1, 1911. While the million dollar price tag was impressive, the Connor Hotel, completed only a couple years earlier, had also a hefty expense. The metropolitan Joplinites were growing use to expensive additions to their city.

Valentine’s Day in Joplin brought confirmation from Kansas City Southern president, Edson, that the project was assured with the successful sale of bonds. Jesse Osborne, now former mayor (replaced ironically by the opposition councilman Guy Humes), declared, “The definite announcement that Joplin is to have the handsomest new union depot in the state in spite of the efforts of a narrow-minded faction to oppose the plan, marks an epoch in the history of this city.”

The day before, the Globe offered an editorial entitled, “Victory and Vindication.” The opinion piece began, “This Union Depot is a betterment of such big and splendid utility, and a project of such substantial promise in many ways, that the people have endured delay and disappointment in a cheerful spirit. Of the ultimate realization of the undertaking there has never been any honest doubt, though the influences which for political purposes, attempted to defeat the ordinance known as the Union Depot franchise have periodically striven to poison the public mind into thinking that this great public improvement was only a hazy, distant dream.”

The achievement of the union depot was seen as one of the top achievements by Joplin democracy, whereas the will of the people triumphed over the opposition of a well-funded minority opposition. It's presence was ranked with the Connor Hotel, the fantastic automotive fire department, and other improvements.

The piece was divided between praise for the reassurance brought by the sale of the bonds, and in typical inter-paper rivalry, prods at those who opposed the depot franchise, such as the News Herald. In an earlier piece, the Globe had noted of James Campbell, the Frisco owner, that it would support Campbell in any quest to build a new Frisco depot in Joplin (rumors of which were plenty). However, as victory was indeed within grasp, the paper took time to lambaste the current Frisco depot located at 6th Street in scathing terms, “One of the very prompt results of this Union Depot will be the passing of the imposition at Sixth street which the Frisco still presumes to call a depot. We have been told with the pathetic trembling of lips that grieved at the confession of helplessness, that the sodden, barbarous inadequacy at Sixth street was permitted to remain because the Frisco didn’t have the money to build a better depot.” More over, the Globe refused to accept “manifestly false absurdities,” and pointed to the millions spent by the railroad on its facilities in nearby Springfield. In the haze of victory, with no little forgiveness for those who opposed the depot, the newspaper helped voice the frustration of a city impatient to continue its climb to greatness.

Two days later, the man who had helped to personally usher the franchise which bore his name, John Scullin, arrived in Joplin. The agent of the Joplin Union Depot company recounted the delays which the company had encountered due to the opposition of what Scullin described as a “faction who handicapped the initial steps for the erection of a station.” None the less, Scullin acknowledged that wiser heads prevailed, and promised the station would be completed by January 1, 1911.

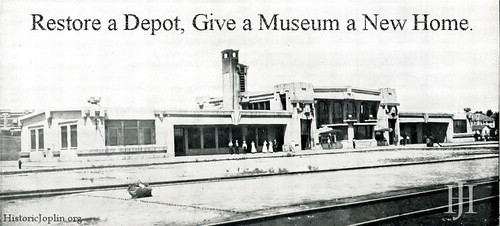

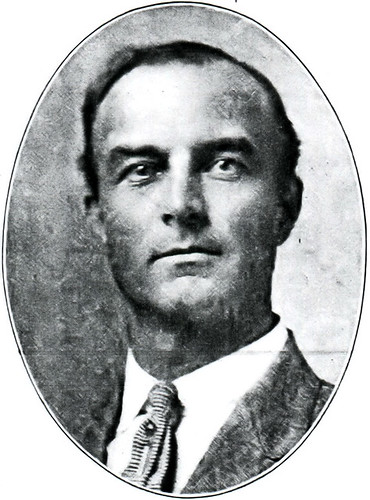

The first view of the Union Depot which greeted the readers of the Joplin News Herald on March 1st

On March 1, 1910, the people of Joplin were offered their first glimpse of their future union depot. Printed prominently across the top of the front page of the News Herald was an architect’s rendering of the front of the station. Kansas City Southern chief engineer, A.F. Rust, introduced the building, “Louis Curtiss of Kansas City is the architect of the depot and we believe he has done well. As you may notice, the middle section of the building is two stories high and on the second floor will be the offices. At the right will be the baggage and express offices, while the east end will be occupied by the restaurant.” Rust went on to add of the station, “The construction will be of concrete faced with stone. Title will play a prominent part in the interior decorations, the mission effect being carried out in a happy fashion. Entrance to the station from the rear will be from Main by a driveway that will circle at the back away from the trains.” Rust finished his appraisal of the station with yet one more proposed cost for the station at $75,000.

The city now knew what to dream of, when it waited in anticipation for construction to begin and for what it hoped to be a boastful addition to their home at the start of the next year. Between then and the station’s opening, a long road yet remained to be traveled.

Sources: Joplin News Herald, Joplin Daily Globe