In previous posts we’ve covered shootouts, robberies, and prostitutes. Sometimes, however, officers of the law made the headlines — for the wrong reasons.

On a fall evening in 1906, Joplin Patrolman Johnson was standing outside the Mascot Saloon at the corner of Tenth and Main. It was 9:30 at night. The sun had set and it was a cool Friday night. Johnson may have anticipated trouble, but not until Saturday night, which was when the miners were paid their weekly wages. Special Officer Ben Collier swiftly walked past Johnson and entered the Mascot.

Shots rang out from inside the saloon. Johnson dashed inside and saw Police Day Captain Will J. Cofer standing with a gun in each hand. One gun belonged to Special Officer Ben Collier; the other, still smoking, belonged to Cofer. Cofer laid Collier’s gun down on a beer keg and then began to holster his pistol. Patrolman Johnson, however, demanded, “Give me those guns.” Cofer obliged. Johnson then noticed the motionless body of Ben Collier lying on the floor of the saloon. Johnson checked for a pulse, but found Collier was dead.

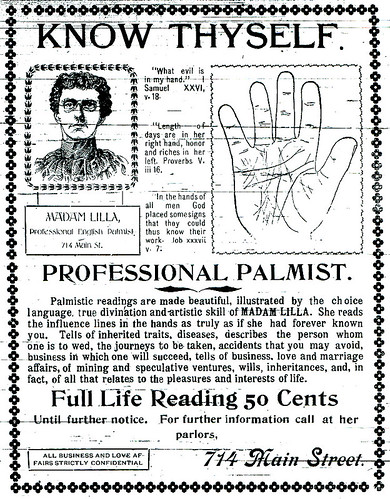

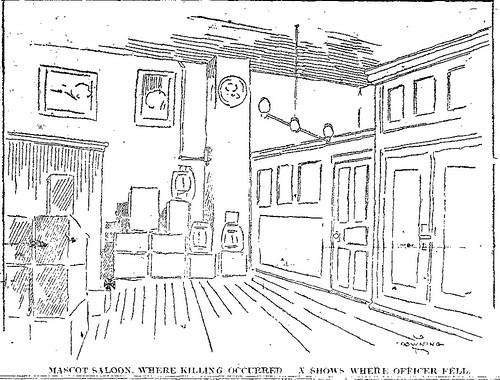

Sketch of the interior of the Mascot Saloon

Johnson took Cofer into custody and headed for the city jail. On the way Johnson was met by Assistant Chief of Police Jake Cofer, who was Will Cofer’s uncle (and was commonly known around Joplin as “Uncle Jake” as he had served for several years on the police force), who took charge of his nephew. Upon arriving at the city jail, Jake Cofer asked Will to remove his police badge, and then locked him in a jail cell.

It appears that the difficulty between Will Cofer and Ben Collier began over a woman named Rose Proctor. She was described as a “small and pretty blonde” who lived at 1216 Main Street. Proctor was reportedly estranged from her husband who still lived in Illinois. She may have come to Joplin due to the fact she “had several married sisters” living in Joplin.

Will “Rabbit” Cofer was a twenty-three year old married father of five year old son. At the age of 17, he married a woman from Pierce City who was ten years his senior. His father, Tom Cofer, served as Joplin Chief of Police before moving to Portland, Oregon. Will stayed in Joplin and worked as a blacksmith and in the mines before joining the police force. He had only been on the police force for a year, but was supposedly a satisfactory officer.

Ben Collier, who, at age 55, was older than Cofer, arrived in Joplin in the mid-1880s. He worked as a butcher for several years before became involved in mining. Collier eventually served on the police force, but left to become a private watchman. He was still working as a private watchman when he tangled with Cofer. Collier’s first wife had died and was allegedly estranged from his second wife who lived in Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Cofer and Collier had quarreled in the past. A Joplin Globe reporter had been standing on the street with Cofer the previous Wednesday when Cofer reportedly pointed to Collier and remarked, “There stands a fellow who has sworn he will kill me and I am afraid that he will try to do it before long. If he would only come to me and tell me about it, it would be a different matter and we might get things straightened up, but he always talks behind my back.”

Members of the Joplin police force knew that the two men disliked one another and did their best to keep them apart. Upon learning the Will Cofer was in the Mascot Saloon with Rose Proctor, Uncle Jake Cofer had sent word to his nephew that if he [Will] had any respect for him, Will would leave both the saloon and Rose. Will Cofer, however, ignored his uncle.

Later that night, around 8 o’clock, Ben Collier appeared at the boarding house room that Rose Proctor called home, but was told she was not home. Collier then spent an hour visiting with Proctor’s next door neighbor, May Stout, who told Collier that Rose was out with Will Cofer. When he learned that Rose was with Will, Collier allegedly remarked, “I’ll kill him if I can find him tonight.” He then stalked out of the boarding house. May Stout tried to call the Mascot Saloon to warn Will and Rose, but failed to reach them in time. That’s when Ben Collier strode past Patrolman Johnson, entered the saloon, and a series of shots rang out.

There were only a few witnesses: “Red” Murphy, a cook at the Sapphire restaurant; Fred Palmer, bartender at the Mascot Saloon; and Rose Proctor. In her statement to the police, Rose said she and Will Cofer were drinking a bottle of beer when Collier came in. Collier called out, “Rose, come to me.” Rose coyly asked, “What do I want to come to you for?” Cofer, looking at Collier, offered to take Rose home.

Collier, enraged by Cofer’s interference, growled, “I have been looking for you and I have got you now!” The two men were standing roughly six feet apart when Collier drew his .44 caliber revolver but Cofer beat him to the draw. Cofer managed to hit Ben Collier three times above the heart with his .38 caliber revolver. Collier fell to the floor dead.

A sketch of Will Cofer

Rose Proctor’s testimony was verified by the two other witnesses. Upon examination, Collier’s revolver was half-cocked and had not been fired before Collier fell dead. Jasper County Sheriff John Marrs arrived and ordered Collier’s body be sent to the Joplin Undertaking Company.

At the coroner’s inquest the next day, Rose Proctor and Fred Palmer, the bartender, testified that Collier pulled his gun on Cofer the minute he entered the saloon. Proctor also testified she had attended “the races at Carthage” earlier in the week with Cofer. After Collier found out, he waved his revolver at her and threatened to pull the trigger.

Patrolman Henry Burns testified that Collier had told him that morning that he would “get” Cofer “before night.” Joplin Police Night Captain Ogburn testified Collier had made threats against Cofer earlier in the year. After the coroner’s jury made a trip to the Mascot Saloon to see the scene of the crime, the members made their decision: Cofer killed Collier in self-defense and was free to go. Cofer shook hands with his friends and then resigned from the Joplin police force.

By 1910, Will Cofer and his wife Amelia were living in Portland, Oregon, where he shoed horses for a living. According to the federal census, their son died between 1906 and 1910. The couple was childless.

Curiously, in 1920, Will’s wife is listed as Rose. His first wife, Amelia, either passed away or the couple divorced. It seems unlikely, however, that this was Rose Proctor as this Rose listed her birth place as Oregon. What is certain, though, is that a shooting took place in a Joplin saloon on a crisp fall night and Ben Collier lost much more than his heart.

Sources: Joplin Globe; 1900, 1910, 1920 federal census