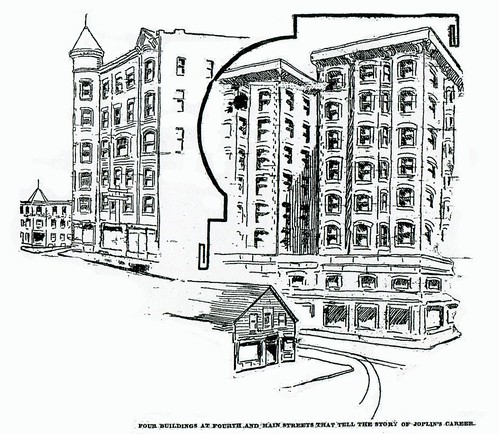

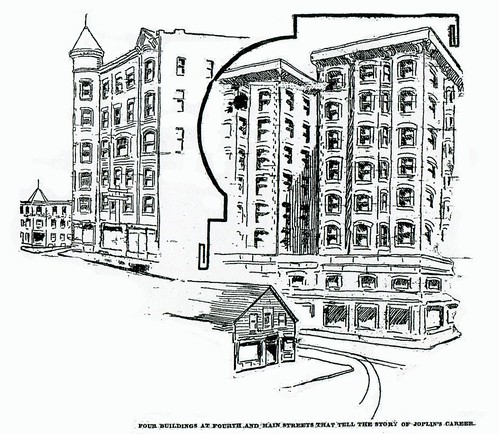

The four buildings of Fourth and Main Street

More than a century ago, a visitor to the bustling growing city of Joplin could have stood on any of the four corners of the intersection of Fourth and Main and viewed the history of the former mining camp writ large in the buildings about him or her. The ability to taken in the “epochs” of Joplin’s history with a glance was not missed by Joplinites of the era, and one reporter of a city papers wrote,

“The noonday shadow of the old frame landmark of the early seventies almost brushes the base of the half million dollar edifice that represents the highest achievements in building construction of the twentieth century. The monument to the days of Joplin’s earliest settlement seems to crouch lower and more insignificant than ever, now that a colossal hotel has been erected within less than a stone’s throw of it.”

The “old frame landmark” was the Club Saloon owned by John Ferguson until his death on the Lusitania (learn more about that here) and the “half million dollar edifice” was none other than the Connor Hotel, completed in 1908 and considered by many the finest hotel of the Southwest. Unmentioned above were the Worth Block and the Keystone Hotel. A visit to the intersection today, however, would find none of these buildings remaining.

A step back in time, when these four buildings still stood, would let the visitor see Joplin’s history as built by man. For reference by today’s geography, imagine that you are standing on the northwest corner of Fourth and Main Street with the Joplin Public Library at your back. Behind you in the past would be the towering eight story Connor, across the street to your right was the two story, wood-framed Club Saloon, where the current Liberty Building stands, to your left was the three story Worth Block, now home to Spiva Park, and directly diagonal from you would be the six story red-bricked Keystone Hotel, gone for the one story brick building today. The same reporter from above offered descriptions of how each of these four buildings revealed the chapters of Joplin’s past. The history that the Club Saloon represented was one of a camp fighting to become a city.

“When the frame structure at the southwest corner was the leading structure of the city, the site of the present Connor Hotel was a frog pond and the deep booming of the inhabitants of the swampy places echoed over the sweeping stretch of open prairie land.”

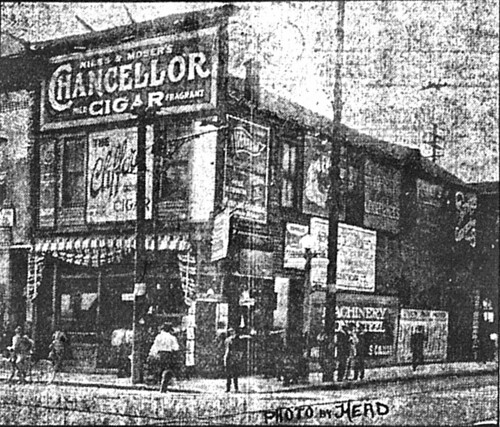

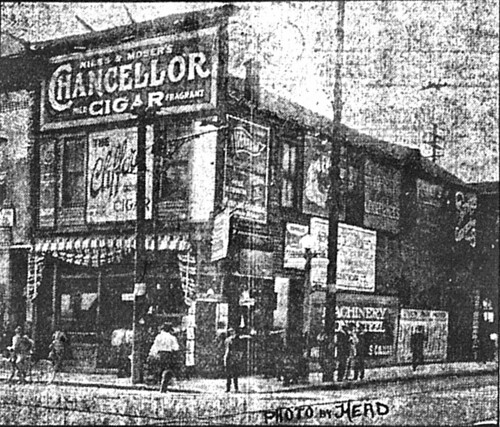

The Club Saloon shortly before it was razed.

At the same time, the land where the Keystone Hotel eventually grew, was a mining operation owned by Louis Peters. The reporter is quick to allay fears of sink holes and noted that the drifts and shaft of the mining were filled before the property was sold. The Club Saloon’s home was bought from its owners in Baxter Springs, Kansas, by Oliver Moffett (E.R. Moffett’s son), Galen Spencer, and L.P. Cunningham, among others, and brought to the young mining camp to become the town’s early center. It was first used as a grocery store and flanked on either side of it were “shacks of disreputable apperance.” In the frame building, reportedly, one of Joplin’s early grocers and councilmen, E.J. Guthrie was killed. It was not the only frame building to be brought to Joplin, but those failed to survive for long. The Club Saloon was immuned perhaps because of the temperament of its owner, the ill-fated John Ferguson. Often, he turned down offers to buy it and once Ferguson allegedly declared, “If you would cover the entire lot with twenty dollar gold pieces, it would not be enough. I think I shall keep it.”

Across the street, so to speak, the old frog pond was shortly developed into a three story brick building, the original Joplin Hotel. Described as a “palace” amongst the other contemporary buildings of Joplin, it was given credit for shifting the center of the new city from East Joplin to the area formerly known as Murphysburg. The presence of the brick building spurred the construction of others, particularly on the east side of Main Street. Among those building was Louis Peters, who continued his mining, but also built a two-story building at a cost of approximately $4,600 on the northeast corner. The new building replaced one that had burned to the ground and was built in less than two months, completed in the December of 1877. Later, a third story was added to what was then called the Peters Building, but became better known as the Worth Block when James “Jimmy” Worth became the owner (precipitated by Worth marrying a co-owner of the property).

The Worth Block circa 1902

As slowly a recognizable Fourth and Main Street began to emerge, Joplin was still a young city that had more in common with a mining camp than a growing metropolis. Saloons proliferated, gambling was common, and other vices not spoken of in good company. This period of Joplin’s past was described as so:

A crimson light hung high over Joplin, shedding its rays over a great portion of the town, would have been an appropriate emblem of the nature of the community. Pastimes were entered into with a wantoness that brought to the town a class of citizenship not welcome in the higher circles of society. But if, in those days there was a higher circle, its membership was limited. Society existed but it was in true mining town style. There was in evidence the dance hall, the wine room and the poker table. The merry laugh of carefree women mingled with the clatter of the ivory chips on the tables “upstairs” and the incessant music of the festival places sounded late into the night, every night of the week, and every week of the year. No city ordinance prevented citizens from expectorating tobacco saliva upon the sidewalks; in fact, the sidewalks were almost as limited as was the membership of the exclusive upper circles.

In 1875, a flood swept through Joplin, and washed away homes, flooded mines, and even killed some Joplinites. The damage, in 1875 dollars, was almost $200,000. For all that was lost, the city continued to gain in wealth, growth and citizens. Ordinances and laws were put in place and a more determined citizenship to see their enforcement. The lawlessness that had persisted in the open air withdrew, the “secrets of the underworld of the Joplin…” were not “broadcast as they were…” The surge of mineral wealth saw more bricked buildings rise and the new owner of the southeast corner of Fourth and Main, E.Z. Wallower, saw more to gain in building than in mining. In 1892, construction of the turreted Keystone Hotel began. Not long after, the intersection was just short of the Connor Hotel in its appearance. This was remedied, as noted above, in 1908, just sixteen years later. In that span of time, “many fine edifices were erected.”

Until the demolition of the Club Saloon, at a glance, one could have seen the history of the city. From the very first days when a wood frame building was a sign of progress, up from shanties and tents; and then the brick constructions of the Peters Building that became the Worth Block, as the first inclinations of wealth from mining began to show progress; and finally, the raising of the Keystone and the Connor, when millionaires brushed elbows as they walked the sidewalks from the House of Lords, and Joplin was in the thick of its first renaissance. A visit to the intersection today leaves nothing of this history to be learned at a glance. The Liberty Building, which now stands where the Club Saloon once stood, is a bridge back however, witness to all of the former inhabitants of Fourth and Main Street but the Club that it eventually replaced. As are all the historic buildings of downtown Joplin, so while some of old Joplin is gone, much thankfully, can still be enjoyed and that history known with a glance.