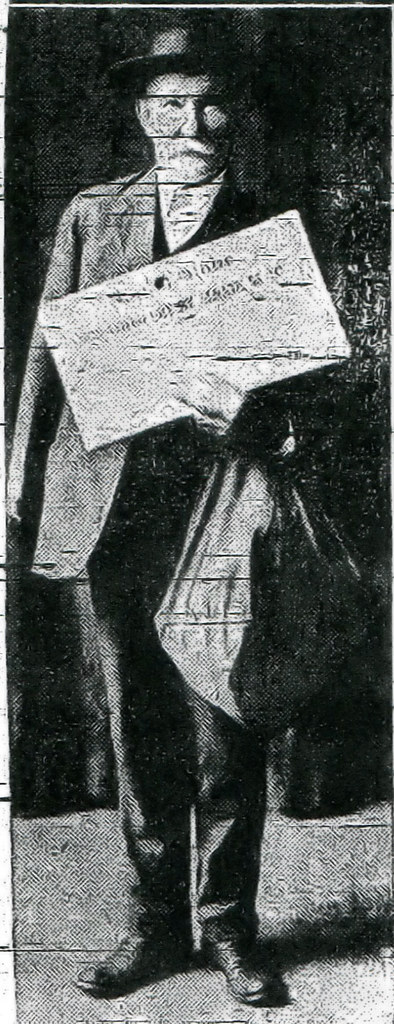

William “Bill” Chenault was a well-known “sporting man” throughout the four state region who made gambling his vocation. He had lived in Joplin for years, but was living in Oklahoma City at the time of his death. The son of a judge from Springfield, Missouri, Chenault “was on the border his entire life.” As a young man, he arrived in Joplin and made “lots of money.” When the town began to grow old, he moved further west to Dodge City and Wichita, Kansas. Bill “was lucky” but made sure to look after the less fortunate. He would reportedly hunt up “some poor stranger who had not been handled kindly by the world and help him, put clothes on his back, or a square meal in his stomach” even though his money was easy come, easy go. That, according to the Globe, was Bill Chenault.

He was also remembered for his sense of humor. One winter in Fort Scott, Kansas, the temperature dropped below zero. When his friends began to complain, Bill put on a thin linen duster and a straw hat, and then went out in the cold. “It is said he nearly froze to death, but he had his fun.” During another cold winter in Wichita, a movement began to try to help the less fortunate, but it was a sham. When Bill found out, he personally went out and bought a carload of coal and oversaw its distribution to the poorest families of the city.

Bill, like most men, had his share of demons. He began drinking and his health subsequently went into decline. Still, the Globe remarked, “those who know him best appreciate the kind disposition he had and the ever willing hand that went out to a friend when something was needed.”

Source: Joplin Globe 1904, Library of Congress