The celebration of America’s Independence Day was no less important a hundred years ago in Joplin than it is today. A principal slogan of the city of Joplin in 1910 was to have a “Safe, Saner Fourth of July for Joplin.” In June of that year, the city council had passed the Kelso ordinance which oversaw the sale, display and use of fireworks. Proponents of the safer and saner Fourth were women groups and the Ministers Alliance. Both Mayor Guy Hume and Chief of Police John McManamy supported the measure and the idea of a “quieter Fourth.” Further support was also sought by the local school systems. Unsurprisingly, the motivation for the ordinance had been to reduce the injuries from the celebratory play with explosives. If injuries could be reduced it was hoped the city could proceed with more support for the holiday. The “Sane” Fourth motto was also raised the next year in 1911 and reinforced by a city ordinance that prevented the sale of firecrackers more than 2 inches in length, as well “exploding canes and blank pistols”.

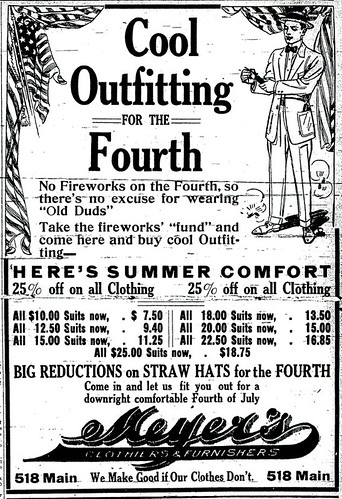

If people were not buying fireworks, Joplin shopkeepers likely hoped they would do some holiday shopping. One such business was Meyers, which paid for a patriotic Fourth of July ad three years later (when the same belief in a “quieter Fourth” prevailed):

Many in Joplin opted instead of celebrating in town to travel to two of the popular recreational parks in the area, “Since early morning wagons, buggies, autos and street cars have been busy carrying people from the city. Contrary to the usual custom, there seem few people from the country coming to town to spend the day. Both Electric and Lakeside parks are the scenes of great activity.” The bill of events in 1911 for the Electric Park in, located within Schifferdecker Park, advertised a fun and entertaining day:

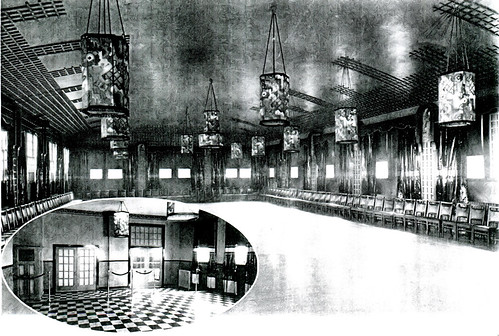

Not mentioned in the ad above was an inviting swimming pool, an escape from the hot July heat. Likewise, as the name reveals, Lakeside Park also offered a cool, aquatic retreat. The attractions at Lakeside in 1911 were several. The Trolley League, a local baseball league of four teams, was scheduled to present a doubleheader. A standard at Lakeside was boating, in addition to swimming, and a band had been secured for a patriotic performance. For those in the mood for dancing, a ballroom was also available.

By accounts, the there was far less room to stroll, as presented here in the photograph of Lakeside Park

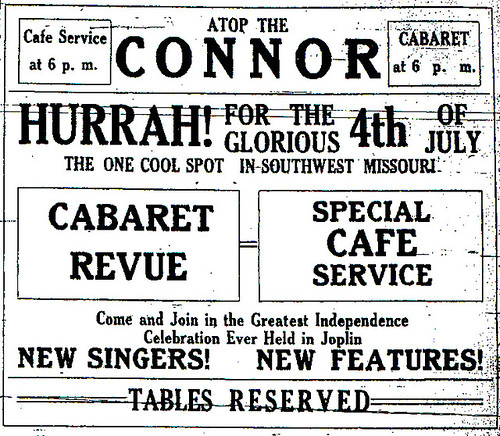

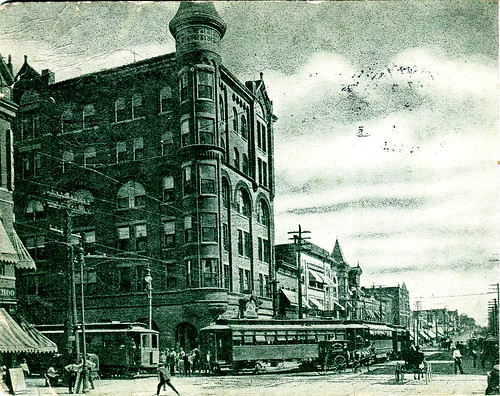

For those in Joplin who opted to celebrate without visiting the parks, one option was to enjoy a meal and music atop the Connor Hotel. 48 booths were made available in “The One Cool Spot in Southwest Missouri,” each designated with a separate flag which represented one of the 48 states of the United States. “A telephone message to the Connor Hotel will be all that is necessary to have a state held.” For those who opted to reserve “a state,” the rooftop garden was decorated with lanterns, flags, and festoonings, and the evening was filled with cabaret singers such as, “Ward Perry, Ned LaRose, Nell Scott and Grace Perry.” Of course, fireworks of some sort were to be expected and for the Connor Hotel diners, a “grand illuminated display of pyrotechnics” among other novelties was offered.

From we at Historic Joplin, have a great Fourth of July!

Sources: The Joplin Globe, Joplin News-Herald

For more on the Connor Hotel, click here!