Once in a while we find a wonderful glimpse into life in early Joplin. One of these is the article, “’Twas Only a Joke” by Robert S. Thurman of the University of Tennessee. Thurman recounts the practical jokes that people played on one another in Joplin at the turn of the century.

Although miners worked long hours in hazardous conditions, they found time to play jokes on one another. Those who suffered the brunt of the jokes were often greenhorns, who Joplin miners dubbed “dummies,” and other outsiders who decided to try their hand at mining.

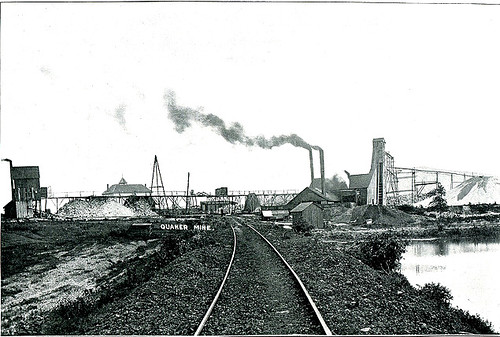

Thurman recounted the story of two men who went into the mining business together at Duenweg. Their mine operation consisted of a pick, shovel, a windlass and can, some drills, blasting powder, and a dummy to help them. The two partners hired a man from Platte County, Missouri, to work as their dummy. Unbeknownst to them, the dummy was an out-of-work miner with plenty of experience under his belt.

The two partners would explain the dummy’s tasks to him in the simplest terms because “a dummy wasn’t expected to know anything, especially if he came from Platte River.” The dummy would listen intently, nod his head that he understood, and carry out his tasks as instructed.

One day the two men were down in the mine shaft prepping a drill hole for blasting. Instead of returning to the surface, they called out, “Hey, Dummy! Do you see that wooden box over by the wagon, the one with a tarp pulled over it?” The dummy replied, “You mean the one with some red writing on it?” The miners yelled back, “That’s it. Now go over to it and get two of those sticks wrapped in brown paper and be careful. Then in the box next to it, get two of those shiny metal sticks and about four feet of the string in the same box. Bring them over here and let them down to us! But be careful with that stuff!”

The dummy, already well acquainted with dynamite from his days as a miner, was fed up with his bosses’ attitude. Having earned enough money to strike out on his own, he decided to have a little fun. He found two corn cobs and wrapped them in brown paper, then stuck a short fuse into each one. The dummy walked back to the mouth of the mine and called down to the two miners, “Are these the two sticks that you want?” The miners replied, “Yeah, that’s them. Did you get the shiny metal sticks and the string?” “Why, shore. What do you think I be? And I decided to be right helpful to you, too. I fixed them up so you can use them right now.”

With that, the dummy lit the fuses, dropped the corn cobs disguised as dynamite into the can, and quickly lowered it down the shaft to the two miners below. Chaos ensued and the dummy had his revenge.

Another trick that miners often played on dummies was to send them after a “mythical tool” called a “skyhook.” One such case occurred at the Old Athletic Mine. The mine had hired a dummy from Arkansas. Unfortunately for Arkansawyers, they were viewed as both inferior and gullible by Joplin mining men. On the dummy’s first day at work, the miners told him, “Dummy, go up to the toolshed and get a skyhook and hurry up with it.”

The dummy nodded his head and headed for the surface. But when he reached the top, instead of going to the company’s toolshed, he headed for town. Upon reaching a blacksmith’s shop, he went inside and asked, “Mister, can you make a skyhook?” The smithy looked at the dummy in surprise, “What do you want?” The dummy repeated, “A skyhook. Can you make one?” “Son,” the blacksmith responded, “someone is pulling your leg. There ain’t no such thing.” “Sure there is,” the dummy insisted, “Now here is how you make it.”

Two days went by and there was no sign of the dummy at the mine. The miners laughed and figured he was too embarrassed to return. But toward the end of the second day, the mine whistle sounded two blasts, which meant everyone had to come to the surface. As the miners reached the top, they saw the mine superintendent, the dummy, and the biggest pair of ice tongs they had ever seen.

The superintendent called out to the one of the miners nicknamed Mockingbird. “Mockingbird, this man says you and the boys sent him after a skyhook. That right?” Mockingbird, so named because he whistled all the time, sheepishly responded, “Well, I guess we did something like that.”

The superintendent looked at the miners and said, “Well, he’s got it for you, but since I didn’t authorize it, I guess you boys will have to stand the charges for it. That will be two days’ wages for him, the bill for the blacksmith, and the cost of the dray for bringing it to the job. Now, three of you boys take that skyhook and hang it over by the office so you know where it is in case you ever need it again.”

Miners were not the only ones who played tricks. As was common in the Ozarks, newlyweds were often treated to shivarees. Sometimes the friends of the young couple would surround the house and ring cowbells and bang pots and pans all night long. Other times they would be taken to a nearby pond, stream, or horse trough for a dunking. Or, the couple would return home and find their furniture had been unceremoniously rearranged.

One couple, Dan and Frances, were determined to avoid any such foolishness. They decided they would stay in their house, lock the doors, and not come out. Their friends soon arrived and began yelling for them to come out. Dan and Frances, however, turned out the lights. Soon it dawned on the group of friends that the couple had no plans to come out. But one of the young men had an idea and promised he would return shortly with a solution.

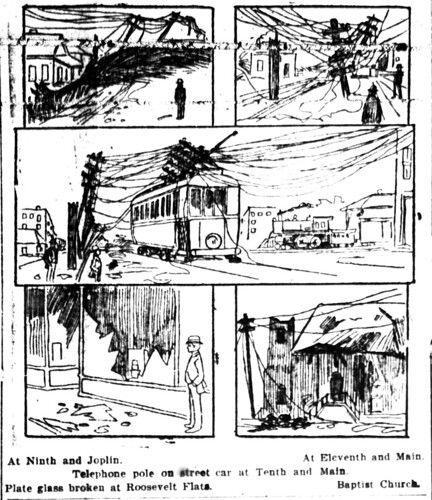

Upon his return, the young man had a stick of blasting powder, a cap, some fuse, a drill, and a hammer. He and the others drilled a hole in the mortar of Dan and Frances’ stone house, put in powder, tamped it very lightly to avoid doing damage, and lit a match. Within seconds there was a small explosion that shook the whole house and made pieces of stone fly. Dan and Frances came flying out of the house to the sound of their friends laughing and yelling, “Treats! Treats” But to make sure there were no hard feelings, a collection was taken to repair the house, and given to the couple.

But not all jokes in Joplin ended on a happy note. There were two rival saloonkeepers, whom Thurman called Jack and Billy, who often fought with each other. A bunch of loafers in Jack’s saloon began to kid him that Billy was out to get him and that he was a crack shot. A few weeks passed and the loafers once again began to tell Jack that Billy was mad at him and was “going to take care of you.” Jack, believing their lies, began to worry. He told the loafers that he could take care of himself.

The next day, around noon, Billy left his saloon carrying a bucket. He crossed the street and headed toward Jack’s saloon. The loafers at Jack’s saloon yelled, “Jack, better watch out! Here comes Billy and he’s got something in his hand!”

Before anyone could stop Jack, he grabbed a pistol from underneath the bar, stepped out onto the sidewalk, and yelled “Billy you ——! Try to kill me, will you!” He then fired at Billy, killing him instantly. Jack, realizing what he had just done, slowly walked down to the railroad tracks and sat down, shaking his head in disbelief. He was eventually arrested, convicted, and served a ten year prison sentence. The loafers who had started the unfortunate affair went free.

Thurman noted that practical jokes were rarely carried out in Joplin after the 1930s. One woman told him, “You can’t joke strangers because they don’t know how to take it.” Another person observed, “We don’t have the gathering places anymore where we can think up devilment. When I was growing up, we’d loaf down at the general store and things would just sort of happen. You can’t do that down at the A & P Supermarket.”

Mockingbird, the miner who took part in his fair share of pranks, told Thurman, “People have a lot of ways of being entertained today. They keep busy either watching television or doing something. They don’t have the time to sit around and think of tricks. And I don’t think they would get by with pulling these jokes on the job. Bosses would not put up today with some of the things we did back forty years ago. Work is more business today; if a guy pulled some of these shenanigans on a job today, he’d get fired. But there’s probably a better reason. I think people are now more grown up today. That kind of humor is just out of place now.”