In the fall of 1910, should one have passed through northwest Joplin in the area between Smelter Hill and Chitwood, they would have noticed a large encampment. At first glance one might assume it was a Gypsy caravan, but closer scrutiny would reveal that instead of wagons, the group was made up of railroad cars, including: three bunk cars, two dining cars, one kitchen car, one tool car, one office car, one private car, thirty dump cars, a seventy ton Bucyrus steam shovel, a grade spreader, and four drill rigs. It was described by a reporter as a, “moving city supplied with electric lights and city water.”

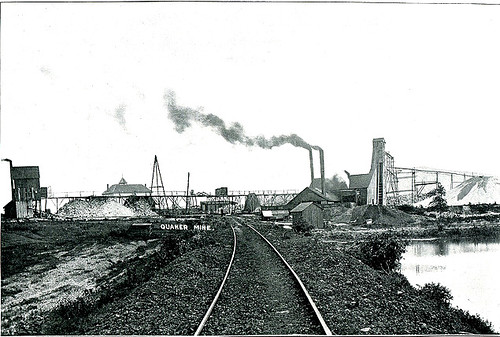

The Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad, commonly known as the “Katy,” was building a line through northwest Joplin. The Walsh-List-Gifford Construction Company of Davenport, Iowa, was responsible for the completion of the new line. The company had previously been engaged in Stillwater, Minnesota, after completing a railroad grading project. One hundred and twenty-five men were employed, most of whom were Belgians. They were required to work ten hours a day, seven days a week. Very few of the men had their wives with them, save for William M. List, who was head of the outfit.

List, described as a “heavy built young man of 34, with a world of power in his massive shoulders and fog-horn voice that thunders past the long lines of his faithful employees with an astonishing effect.” List yelled at his workers, “Here you —- —— —– lazy devils, get a move on; you’re too slow to catch a cold. Get busy there, damn you; don’t you go to loafing on me or I’ll take you to a cleaning!”

If Mrs. List had any objections to the way her husband talked to his work crew, the reporter did not notice. She traveled with her husband on his work assignments, although they had a home in Davenport, Iowa. The Lists were joined by John O’Callahan, superintendent; J.J. Hallett, engineer; and C.H. Swartz, stenographer. F.C Ringer of Parsons, Kansas, oversaw the operation of the steam shovel, F.R. Johnson served as trestle foreman, Leo Purcell was the official timekeeper, and D. Degal was dump foreman.

The crew was grading a three and one-fourth mile section of road that stretched into a wide curve from a point on the main line of the Katy to the new Union Depot. The reporter who visited the site remarked, “Although seven working days constitute a week’s toll, the laborers seem to like the steady grind. In the evening, they gather in groups and gossip, or visit the commissary car for tobacco or new toggery. Any needed work garment may be purchased at the camp.” Work took its toll as the reporter could see that more than one laborer was “wearing a bandage about his head or his hand.”

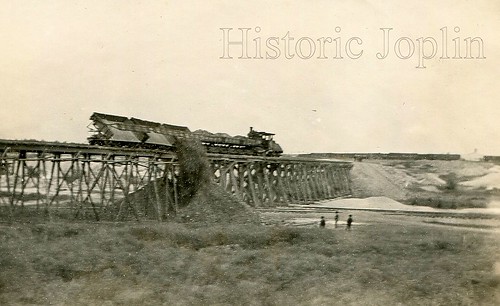

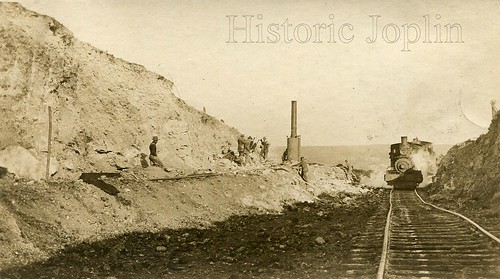

To carry out their work, workers had break the ground using power and dynamite. The drill rigs were used to bore holes into the roadbed to ensure the ground was soft enough. Some of the drill holes ranged from five to thirty feet deep in places. When the holes were finished, they were “squibbed,” which meant that light blasts of powder were placed in the holes to open up the ground even further. After setting off the light blasts, large kegs of black powder and entire cases of dynamite were placed into the holes and set off. After the ground was properly softened up, the seventy ton steam shovel was brought in to scoop up rocks and dirt at four scoops a minute. It was estimated that the steam shovel could remove 2,500 cubic yards of dirt in a day. The shovel would then dump the dirt and rocks into cars situated on a sidetrack built alongside what would become the main rail line. When the cars were filled, they were pushed by a locomotive to a spot where spots needed to be filled in with dirt. The spreader would then be brought in to smooth the dirt in place.

The crew estimated that the project would be completed by January, 1911. After that, their next assignment was unknown, but they could expect to travel anywhere from Maine to California.