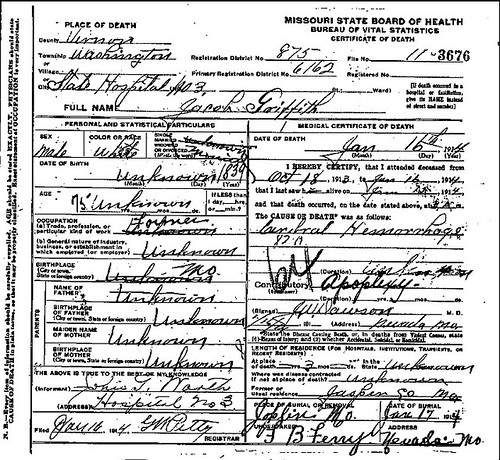

Joplin’s North End was riddled with “immoral resorts” filled with young women. Mamie Johnson was one of many who walked the streets of Joplin. Her life tragically came to an end at the age of thirty-three after she abandoned her husband of four years and two children and took up the profession of a scarlet woman. But her life as a lady of the night must have worn her down, for in the end Mamie’s life was cut short by her own hand.

Mamie, whose real name was allegedly Minerva Rickey, was the daughter of a “well-to-do” farmer from the Kansas City. At a young age she eloped with John Gordon, a young farmer, and settled down. After four years and two children, however, Mamie left her family and strolled into Joplin and a life of vice. Shortly before her death, she had confided to an aunt who lived in Joplin that her husband had mistreated her. The two had reportedly divorced.

One day life was too much for Mamie to bear and she overdosed on ten cent dose of morphine. She was discovered in her room by Frank Wilsey, a laundryman for the Empire Steam Laundry, when he dropped off a bundle of clothes at her room. Word quickly spread throughout Joplin’s tenderloin district and “many touching scenes were witnessed as the unfortunate creatures crowded about and gazed upon the face of their dead sister.” A letter was found in her room addressed to Bessie Blair.

The text of the letter read,

“Joplin, Mo. July, 27, 1898.

Dear Friend Bessie:

I will write this for you and leave it for you. I may not get to talk to you or see you anymore. But my bedroom suit you can have for that fine, but give my clothes to my aunt. That is all I want, but would like for you to come as I want to send word home. I would like for you to see them as soon as possible, for my clothes, my trunk, and things is all I ask of you to let them have. Well, I am satisfied and hope you will be. Tell them to go down to the wash woman’s and give up three dollars for clothes there. I would like to have my aunt come as soon as you get this note.

Do not think nothing as you know what caused it. You will not be out nothing as my folks will take care of me. I suppose you will be satisfied when you see, anyway. You have been a friend to me and not a friend. And I hope when the girls see this they will take warning by me. Bessie, it is hard to do, but I cannot help it. I hope you will be satisfied with Minnie [Mamie’s roommate] as she is a good girl, and will treat you right. I send my love and best regards and hope you will not take a foolish idea like I have took. Kiss them all for me. Tell Pearl she is all right. Time is drawing near and will have to close.

Good bye.

from your Mamie Gordon to my dear friend Bess, 1,000 kisses to all you I will go to hell tonight.”

Interestingly, the letter was dictated by Mamie to her lover, Ernest Boruff, who testified at the coroner’s inquest that the two had quarreled a few weeks earlier after some of his clothes went missing. They quarreled again after he wrote the letter for her and he subsequently left. He claimed that he did not suspect Mamie had suicidal intent and swore that she “was not in the habit of using morphine.” Bessie Blair also testified at the coroner’s inquest and stated that Mamie had threatened suicide several times during the past month.

After Mamie Gordon’s funeral, the coroner’s jury issued the following verdict:

“We, the jury, find that Mamie Gordon came to her death form an overdose of drugs, taken by herself presumably with suicidal intent.”

W.M. Whiteley, Coroner

Dave K. Weir

Samuel Cox

A.C. James

J.M. Graham

Ed Trimble

A. Malang

Life as a prostitute was not a happy one, and more likely than not, one that women simply fell into due to misfortune and bad circumstance. At least some had addictions to cocaine or morphine, and as Mamie Gordon’s letter warned, one that could easily end in the death of a soiled dove.

Source: Joplin Globe