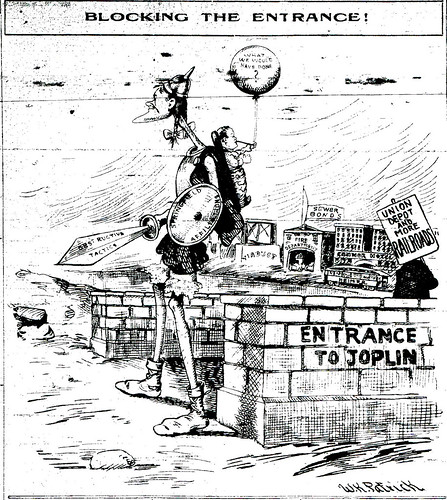

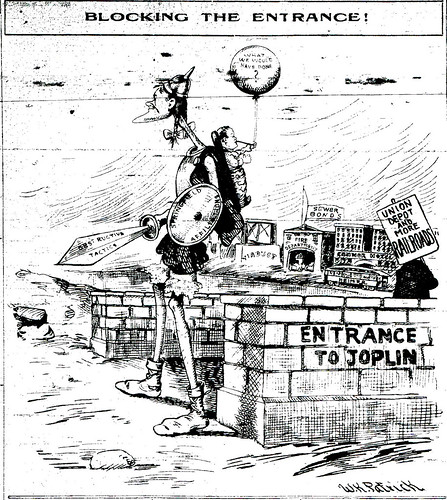

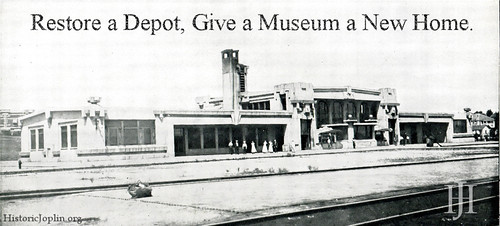

An editorial cartoon from before the Union Depot was built, which implied others were trying to obstruct its construction. Now is not the time to balk at renovating the depot as a new home for the Joplin Museum Complex.

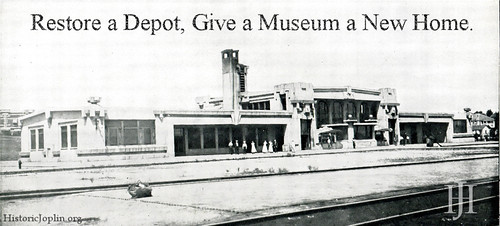

Today’s Joplin Globe has two articles on Joplin’s Union Depot and its proposed renovation for use as the new home of the Joplin Museum Complex.

Isn’t it funny that the Joplin Museum Complex howled and yowled earlier this year that the Union Depot was in too bad of shape to restore? Remember all that talk about “water in the basement” made it unusable? It’s mind-boggling that an organization dedicated to the history of Joplin would just turn up its nose to restore one of Joplin’s architectural crown jewels, isn’t it? Particularly after a contractor has stated the depot is in sound shape for renovation.

It’s time to be blunt.

If you have ever visited the Joplin Museum Complex, you know that it is not impressive. One of us visited it as a third grade student years ago and on a visit last year found that little, if anything, has changed. (Creepy mannequins, anyone?) The exhibits were pretty much the same. Rocks and minerals lay spread out with labels but no interpretive information. Rusty old mining equipment is outside exposed to the elements without meaningful information for visitors. There are cheesy exhibits on the Empire District Company, the National Cookie Cutter Museum, and the Joplin Sports Hall of Fame.

Why has the museum board seemingly failed to financially support the museum over the years? Trustees are expected to support their institution through their own financial generosity as well as lobby individuals of influence and wealth to give financial, legislative, and/or other support to the institution. At the very least, can they not pony up enough money to pay for a grant-writer to bring in money for new exhibit materials?

A move to the Union Depot would present the chance for the Joplin Museum Complex to reevaluate its exhibits and pare down those like the Cookie Cutter Museum that simply have nothing to do with Joplin or its history. It’s an opportunity to redesign and improve relevant exhibits that as well for the trustees to step forward and act to help improve the museum.

Board member Clair Goodwin (a sports columnist for the Joplin Globe) was quoted as saying, “The good thing is, people are concerned about the museum.” Mr. Goodwin mistakes the enthusiasm of the public for the renovation of the Union Depot and the north end of downtown Joplin as support for the museum.

In April it was clear that the public did not support the museum’s aggressive attempt to take over Memorial Hall. It is doubtful that the public has had a change of heart. What is clear, however, is that the public supports the continued renewal of downtown Joplin and the Union Depot. Anyone who appreciates architectural beauty, as many do in Joplin, that the Union Depot is a gorgeous building that deserves to be restored and preserved. Moving the Joplin Museum Complex to a restored Union Depot will kill two birds with one stone.

When board member Allen Shirley says, “The Joplin Historic Society wants a larger museum, but also ‘has an obligation to protect and preserve the exhibits that have been placed in our hands,’” he and the rest of the board need to jump on this opportunity while it exists. This is not the time to twiddle one’s thumbs.

Allen Shirley has been described in the Joplin Independent as a “pharmaceutical sales executive” who was appointed to the Missouri Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (MACHP) by former Governor Matt Blunt (we assume that as a long time Republican Mr. Shirley was placed on the MACHP by Governor Blunt as a political patronage position and not for extensive historic preservation experience/expertise).

Shirley apparently likes to collect old newspapers that he wants to one day dump off on the Joplin Museum Complex. This is absurd for two reasons: one) newspapers from France’s Reign of Terror do not fit the mission of the Joplin Museum Complex, and, two) the Joplin Museum Complex will not be equipped to care for his newspaper collection. Once again, a collector with eccentric taste tries to dump off his collection on a museum to take care of once he’s dead, i.e. Let the taxpayers of Joplin pay for the care and preservation of old newspapers that have nothing to do with Joplin history.

Perhaps he just wants to make sure there will be enough space for his newspapers in the Union Depot?

The museum board must realize that the will of the people, whom the museum is designed to serve, is for the museum to move to the depot. When their dream of taking over Memorial Hall failed, those who voted against it voiced support then for a move to the depot. If the museum board chooses to balk at this proposal, then the City Council should step in.

We here at Historic Joplin think the only person with vision is Mark Rohr. We have never met him, have never spoken with him, and have never e-mailed him. But from what we can tell, this man is dedicated to improving Joplin. His vision for the north end of Joplin’s downtown would be serve as an anchor and impetus of revitalization for an area that was once populated at the turn of the century with brothels, saloons, and shanties. Keep going, Mr. Rohr! Onward and upward!

Support the renovation of the Joplin Union Depot as a new home for the Joplin Museum Complex!