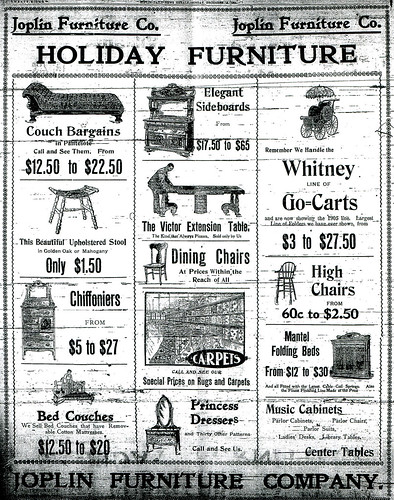

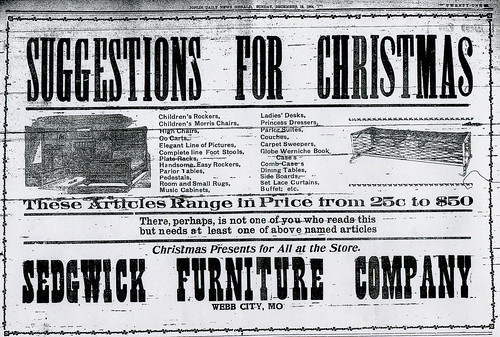

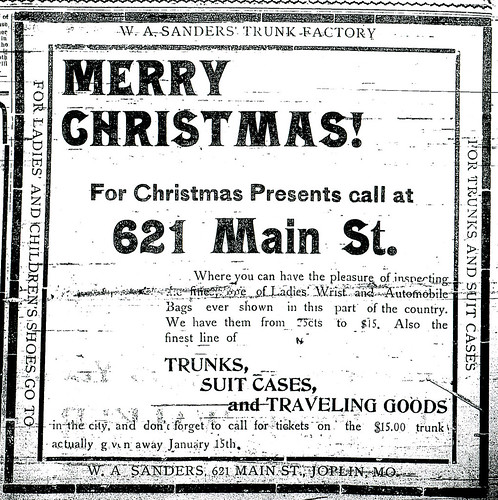

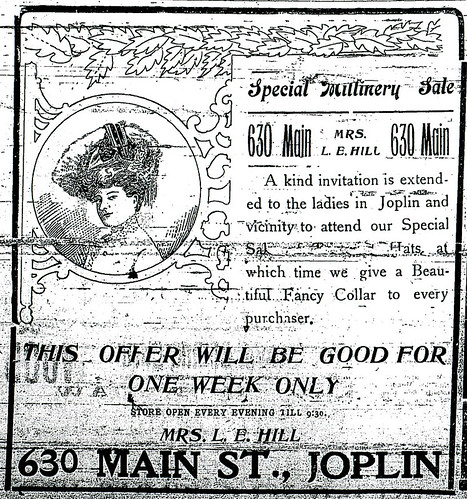

As the memories of this year’s Christmas begin to fade, we’ll take one last look back at Christmas in Joplin. Below are a series of ads from Joplin papers, and if one thing is evident, the commercialization of Christmas isn’t a recent innovation. Click on the images to see larger versions.

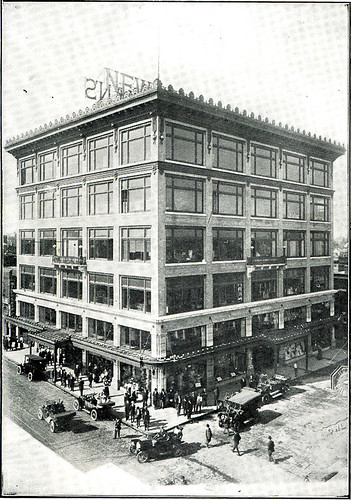

Joplin Globe Coverage of the Newman Building’s 100th Birthday

In case you missed it, last Saturday the Joplin Globe ran an article on the 100th birthday of one of downtown’s most illustrious surviving buildings, the Newman Building. The article, by Debby Woodin, offers both a brief history of the Newman retail business and the building. Additionally with the article are some nice era photographs of the interior of the building when it was at its height. Now the home of city hall, the building is one of the shining examples of why it’s so important to preserve Joplin’s past.

Source: Joplin Globe, Historic Joplin Collection

A Bed In Joplin

Curious to know how much it would have cost to stay in some of Joplin’s hotels?

In 1914, Joplin had an estimated population of 32,073 and had 21 hotels.

Here’s what it would have cost you to stay at some of Joplin’s finer establishments:

Blende Hotel

D.H. McHeeman, Proprietor

Rates: 50 cents and $1.00 per day

Clarendon Hotel

L.S. Branum, Proprietor

Rates: $1.00 per day

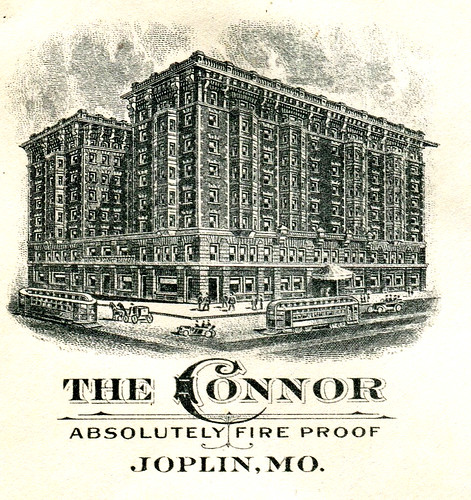

Connor Hotel

T.B. Baker, Proprietor

Rates: $1.00 per day and up

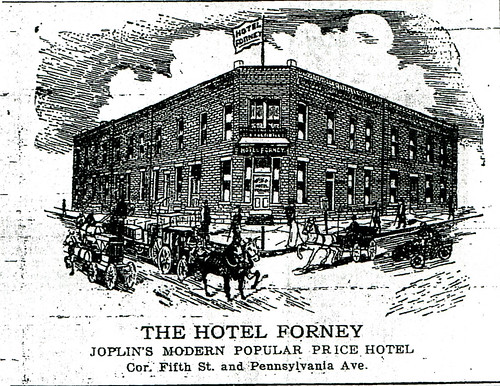

Hotel Forney

I.P. Forney, Proprietor

Rates: $1.50 and up

Keystone Hotel

W.P. Walton, Proprietor

Rates: 75 cents and up

South Joplin Hotel

Gus Searr, Proprietor

Rates: $1.00 and up

Turner Hotel

William D. Turner, Proprietor

Rates: $1.25 per day

Yates Hotel

C.E. Yates, Proprietor

Rates: 1.75 per day

Robert Avett, proprietor of the House of Lords, did not respond to the questionnaire and thus while the hotel was listed in the directory, the cost of a room was not listed. The same went for many other Joplin hotels, including the following: Roosevelt Hotel, La Grand Hotel, Clarkton Hotel, Cliff House, Southern Hotel, Crescent Hotel, and Crystal Hotel.

Hotels in Springfield, hailed as the Queen City of the Ozarks and Joplin’s rival, had similar rates. The finer hotels, such as the Colonial, charged $2.50 and up per day in comparison to Joplin’s Connor Hotel, which charged $1.00 and up.

Source: Official Hotel Directory of Missouri

Glimpses of Yesterday

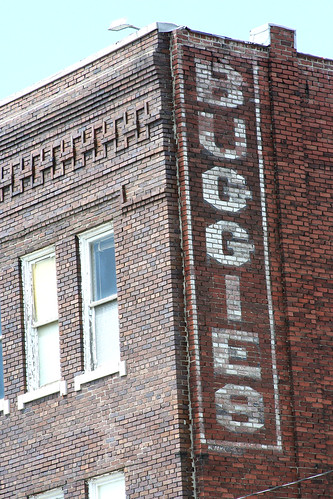

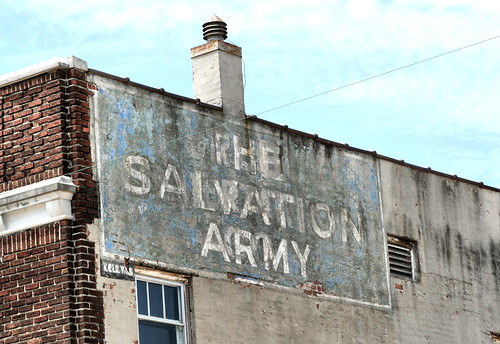

Painted on the sides and fronts of buildings are glimpses of another time in Joplin. Prior to the more popular use of neon, plastic, and other materials, paint, often applied straight onto the building, was the most common form of advertising. A drive around downtown Joplin reveals the remnants of these past days long gone. Below are a number of shots of some, but not all such wonderful instances:

These legacies of the past are easily lost, be it from neglect or intentional destruction. Let’s treasure the ones we have, as they serve as a direct connection to the past and offer a glimpse of another time.

S.B. Corn Returns to Joplin

After having left Joplin 35 years earlier, S.B. Corn returned to the city in 1910, amazed by the city that had replaced the small hamlet he once knew. Upon his arrival, he inquired after several old-timers, including attorneys Clark Claycroft and Leonidas “Lon” P. Cunningham. Corn was saddened to find that both men had passed away. The only men still alive in Joplin that he knew from the 1870s were D.K. Wenrich and E.B. McCollum.

Corn was also disappointed to find that the spot where his smelting plant once stood in East Joplin could not longer be ascertained. He did, however, find the old building that once housed the Senate saloon. Unfortunately, the reporter accompanying Corn failed to report its location.

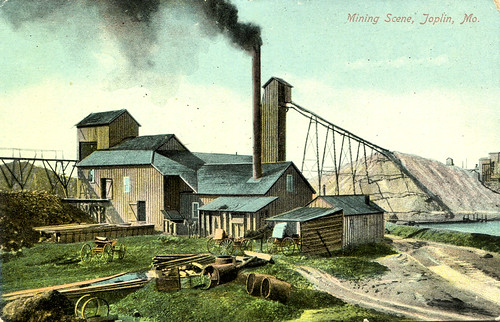

At one time, Corn allegedly owned several hundreds, if not thousands of acres in the Joplin area that extended south into Newton County. Over the years he sold the land off, most of it purchased by Joplin capitalist John H. Taylor. He built his first lead smelting plant in 1870 near the village of Cornwall (now called Saginaw). He built his next smelter closer to Joplin. It used air furnance fueled by wood. As Corn described it, “Hot blast, rushing over the ore, converted it into a molten mass which drained off into kettles. From these kettles it was ladeled out into moulds, and pigs, ranging in weight from 8/0 to 100 pounds, were formed. The metal was hauled over land to Baxter [Springs], Kansas, and shipped by railroad to St. Louis.”

According to the reporter, “Much of the ore smelted was produced from Mr. Corn’s land in the Kansas City Bottoms and was purchased from the lessees. The story is told that the smelting company sometimes paid for one load of lead five or six times, the operators being clever enough to have the same product weighed any number of times.” When this was discovered, duplicate sales were “abolished.” Corn eventually left Joplin and headed east to Pennsylvania where he engaged in the gas and coal business, but on a return trip west felt the urge to see Joplin once more.

He exclaimed, “When I was in there the seventies, there was no west Joplin. This part of the city was nothing but prairie. I feel like Rip Van Winkle, and can ahrdly realize that a city could have grown so rapidly as this one.”

Source: Joplin News Herald, 1910.

A Glimpse of Capitalist Foul Play

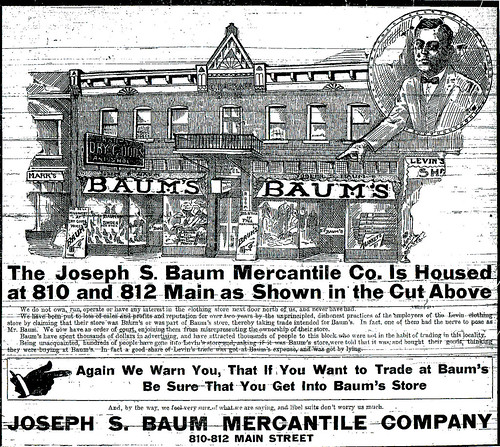

Natural to any mining boom town was the belief that one could setup shop and quickly begin to reap in the riches. As Joplin grew in size, more companies and businesses sprung up to line Main Street and other current downtown avenues. One of those businesses was the Joseph S. Baum Mercantile Company. Another was the Levin clothing store. By chance the two found themselves neighbors to the chagrin of Joseph Baum. By appearances, it seems that Baum was successful and his neighbor decided to help himself to that success by holding his store out as part of his neighbors.

From that point on, Baum Mercantile Company struggled through a 2 year odyssey to force their neighbor to quit their deceptive practices. The practices went so far as one employee of Levin’s pretending to be Joseph Baum, himself. In the end, it took court action to silence Levin’s employees and their deception. None the less, as a glance at the ad will attest, Baum felt it necessary to place an ad in the local paper to further clear up the issue.