When one thinks of cocaine, they may think of the 1980s, Nancy Reagan, and the War on Drugs. Cocaine, however, was in Joplin long before tv commercials showed eggs frying in a skillet while a voice somberly intoned, “This is your brain…This is your brain on drugs.”

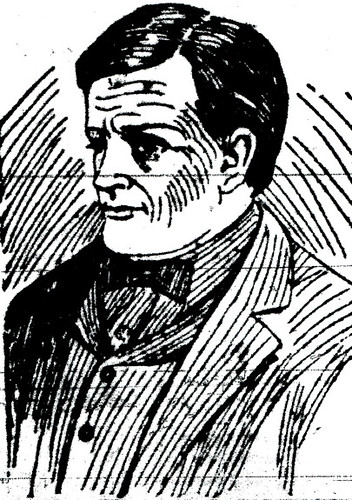

A sketch of Daniel "Cocaine Jimmy" Shannon

Perhaps the most infamous cocaine user in Joplin was Daniel “Cocaine Jimmy” Shannon. One day, Shannon was found passed out behind the House of Lords by members of the Joplin police department in what one physician thought was “the last stage of drug poisoning.” He was taken to the city jail to spend the night and was transferred the next day to the Jasper County Poor Farm in Carthage. One doctor remarked, “He can hardly survive this attack, and at the poor farm the drug will be taken away from him altogether. He is too far gone to be benefited by that treatment, and I am inclined to think that his days are numbered.”

Cocaine Jimmy granted an interview following his near fatal drug overdose. He told a reporter, “I have been a drug fiend for 18 years. The average life of the cocaine or morphine fiend is five years. I think the Lord must have let me live this long in order that I may be cured and live to do some good in this world.”

Jimmy, it turned out, had not always lived on the edge. As a young man, he attended the Chester Military Academy in Chester, Pennsylvania, and then attended a music conservatory in Philadelphia. This fact, the reporter noted, “many of the people of Joplin are ready to believe, for they have heard him play at the music stores. When under the influence of the deadly drug to which he is addicted and at just the right state, he has shown himself many times to be a brilliant performer upon the piano.”

According to Jimmy, his father was wealthy, and even played host to President James Buchanan at the family home in Pennsylvania. But after becoming addicted to cocaine, Jimmy left behind a career as a lawyer, and instead spent his time working on and off as a janitor at the Sergeant building at the corner of Fifth and Main. The reporter observed that Jimmy talked little of his past. One lawyer who doubted Jimmy’s former occupation as a lawyer was stunned when Jimmy began quoting sections from Blackstone’s law almost verbatim. In manners, he was always extraordinarily polite, always thanking anyone who helped him and making sure to say hello to others.

The paper remarked, “Those who knew Shannon in his brighter moments and could see what the man had been and what he might have been, will hope ‘Cocaine Jimmy’ himself that after all the Lord will see to it that he is cured; that he may live to accomplish something in this world.”

A few years later, Jimmy was still alive, and granted another interview to a Joplin reporter. Jimmy was described as a, “little, old appearing man, with a wrinkled face and a tinge of gray in his air, and although he is only 40 years old, his beard, when not closely shaven, is as white as snow.” His cheeks were hollow and there were “great hollows under his eyes.”

Although the moniker “Cocaine” was understandable, there was no explanation as to why he was called “Jimmy” when his given name was Daniel. His friends had pooled enough money to put Jimmy through an unspecified treatment program which seemed to be working until he suffered a painful bout of inflammatory rheumatism and relapsed.

Jimmy told the reporter he first used cocaine while receiving medical treatment at a hospital in the Dakotas. He used small amounts at first so that it was not readily apparent that he was using the drug. He “began the use of cocaine by dipping the needle in it when I wanted to take a ‘shot’ of morphine in order to keep the needle from hurting me. The desire for cocaine grew on me until I now use the two drugs equally mixed.”

He did not like practicing law, so his father set Jimmy up in the musical instrument business. He enjoyed teaching music and soon took “one of the prettiest little women there was” as his wife. Jimmy’s love of cocaine, however, was stronger and he began to abuse cocaine at a greater rate. He abandoned teaching, left his wife, and took all of his money out of the bank. Jimmy proclaimed, “There is not an hour in the day when I do not wish I could be cured of the terrible habit and straighten up and be a man.”

Jimmy told the reporter, “I cannot understand why any young man or young woman will begin the use of cocaine or morphine. My body from head to foot is a complete mass of scars which have been made by the hypodermic syringe.” The craving for the drug was so bad, he said, “there is nothing short of murder that will prevent him from getting it.” On average, he used fifty to seventy-five cents worth of cocaine per day. He then gave a lengthy description of the hellish existence of a cocaine user, described the multiple ways one could use the drug, and then sadly said, “My one ambition is to get enough money to take the cure and if I can get thoroughly cured of the habit I feel that I would never again touch a drop either of cocaine or morphine.”

Sadly, Daniel “Cocaine Jimmy” Shannon did not live much longer. He was discovered unconscious behind Ferguson’s Saloon by members of the Joplin Police Department who carried him to the Joplin City Jail. He was remembered for his daily plea of, “Give me a nickel.” Although he “was a well known character upon the streets, he never figured conspicuously in police court, and was but seldom arrested.” When arrested, it was for begging or for passing out on the street. In his obituary, it was noted that he “was an expert pianist and during his career in Joplin frequently was employed by proprietors of beer gardens and north resorts as a pianist.” Despite three desperate attempts to be cured of his habit, Jimmy died, and his body was held at the Joplin Undertaking Company until family members claimed the body. Where he was laid to rest is unknown, but one wonders if his ghost still lingers on the streets of Joplin, still looking for one last fix.

Source: Joplin Newspapers