In our earlier coverage of the origin of the Joplin Fire Department, we concluded with the transition by the department from horse drawn fighting apparatus to fire fighting equipment mounted on automobiles. This transition did not occur without fanfare or no little publicity.

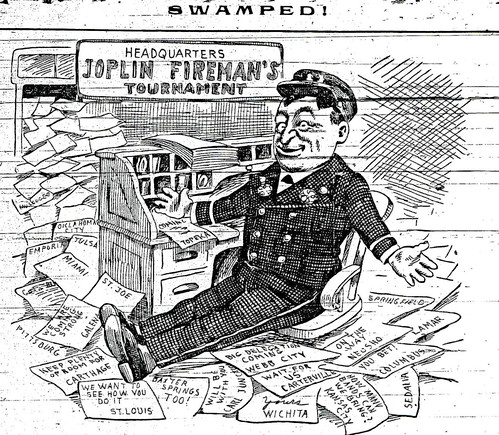

Instead, the Joplin Fire Department opted to showcase their new fire trucks by hosting the Southwest Firemen’s Association annual tourney. The tournament, which was to run for three days, was expected to draw the biggest crowd yet in the history of the tournament. At least 30 teams were expected to come from the four state region to compete in multiple events in teams of 17. The main attraction, however, was the Joplin Fire Department’s new fire engines, which claimed to be among the first in the nation to harness the power of the automobile engine to power the attached fire fighting apparatus. (Previously, the apparatus was merely attached). Also of note, Joplin believed itself the first to attach a chemical tank to an automobile, which combined two of the most modern fire fighting technologies. Highlighting the exhibition would be a race between the 75 horse power fire engines around Barbee racetrack, a first ever in the United States. The News Herald excitedly predicted the experience:

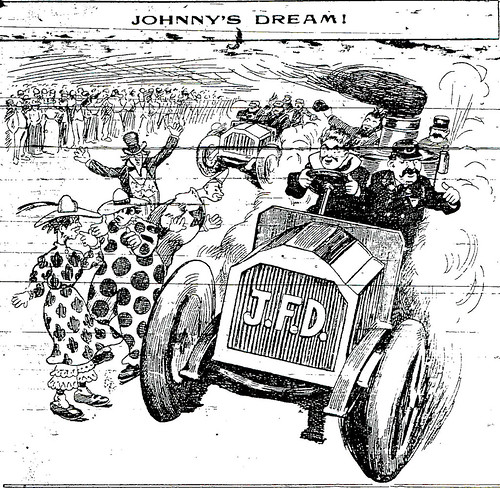

“At Barbee park they will see the big machines on the line, hear the starter’s revolver fired, then with a chug the red devils will be off, sailing around the track, only a mass of bright colors in which the blue of the fire laddies mingles with the gaudy red and gold of the machines, and they will see the machines, only a streak of red, as their drivers send them down the home stretch faster than 75 miles an hour, with the gong of the big fire bells sounding as the winner shoots over the tape.”

Not to be forgotten were the fire horses, who had there own races as well. The horses, still retained by the Joplin department, would have a chance to race against those from other departments before literally being put out to pasture. The big horses which had the hard task of pulling the fire wagons through the streets of Joplin at breakneck speeds, had one last opportunity to demonstrate their ability.

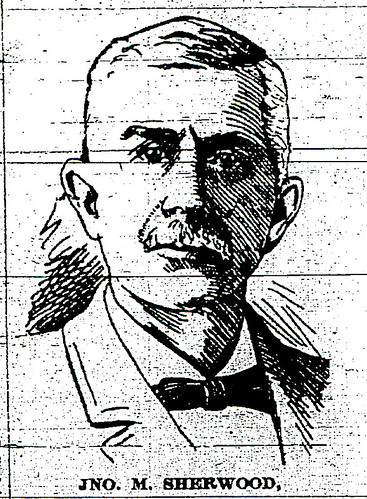

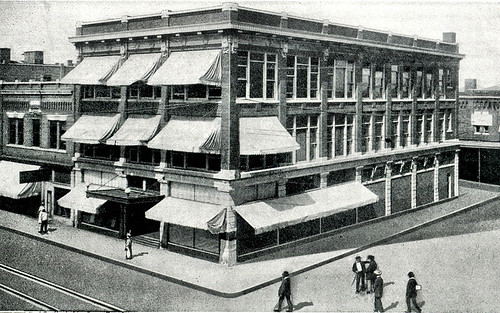

On September 8, 1908, the first day of meeting of the Southwest Fire Association began on a Tuesday morning with the business meeting of the association at the Commercial Club. Mayor Jesse Osborne enthusiastically greeted the firemen, “Joplin wants you to have a good time. The city is thrown wide open to you and if you see anything which you want that is tied down, tear it loose.” Speakers included an invocation by Reverend W.F. Turner, the president of the Commercial Club Col. H.B. Marchbank, as well as two past presidents of the association, and the current president from Neosho, Missouri, Jonathon M. Sherwood. Present at the meeting were 25 delegations from the four states, who opted to adjourn at 10 am.

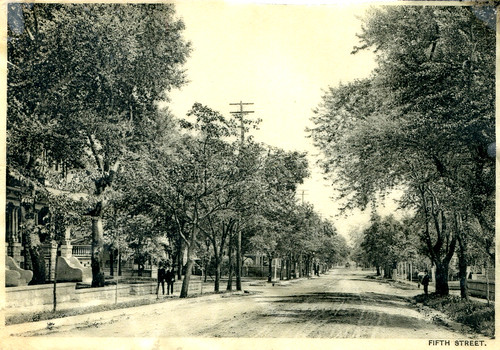

The afternoon must have been a delight to small boys and girls who crowded Main Street and the other streets along the parade route to witness a mile long parade of firemen and their fire fighting apparatuses. It began at approximately 2:30 pm at the central fire fighting station with the vanguard composed of a handpicked squad of 18 mounted police officers lead by Joplin Police Chief, Joe Meyers and his Assistant Police Chief Cofer. Behind them marched a band, and behind this musical introduction, companies of firemen from Galena, Weir City, Scammon, Gas City, Neosho, Carterville. Veteran firemen of the association followed with veteran Joplin firemen right behind them. These veterans pulled a cart with them, the first piece of fire fighting equipment ever employed by the department. Behind them rode city officials in carriages who were trailed by the four automobile engines of the department, as well four horse drawn engines. Over a thousand visitors, it was estimated, had arrived in Joplin for the tournament.

After the parade, crowds gathered at the central fire station to examine the “big machines” which demonstrated their capability and even raced down Main Street in a demonstration and “the speed of the automobiles and the dexterity with which they were handled elicited much applause.” However, the appreciative crowds had to wait until 1pm the next day to see the machines on the race track.

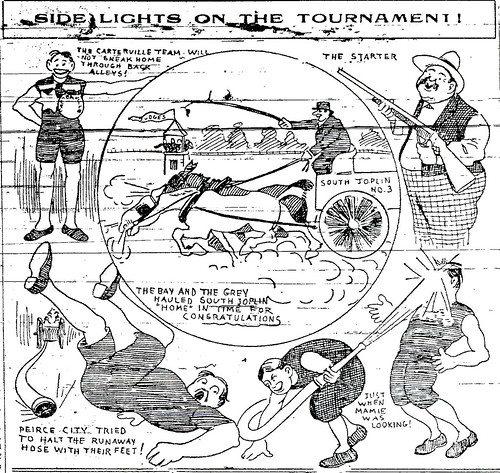

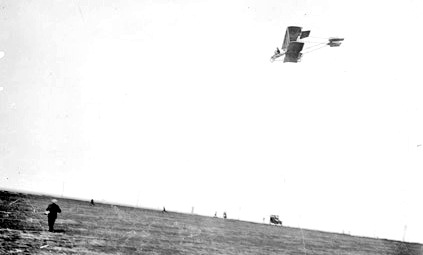

Wednesday saw the main attractions of the tournament with fire engines raced around Barbee racetrack. Nor were the fire departments ready to forget their fire horses with an exciting race between the Joplin departments taking place. Before an estimated crowd of 3,500, the victor of that narrow contest was Station No. 3 of South Joplin. The firemen of South Joplin were pulled to victory by the beloved bay and iron gray fire horses, King and John. They defeated the other Joplin pair of fire horses, Tom and Dan.

“ The horses started on the word “go,” and with a bound were off, throwing dust. With the bells of the wagons clanging, the horses tore around the track, coming down the home stretch with remarkable speed.”

Other competitions involved laying out 150 feet of hose and then “water thrown” to stop the clock. Specifically, teams had to race to a line, then attach a hose to a hydrant and put a nozzle on the hose. It was the firemen from Carterville who ended up excelling at this contest. Numerous other competitions occurred which revolved around other skills essential to the task of fighting fires.

The final day of the tournament was expected to draw even more to Barbee’s racetrack than the 3,500 from the day before. The main attraction was a real demonstration of firefighting by the Joplin stations. A two story wood structure, doused in oil, was built upon the race grounds and set aflame. It was decided before hand that the structure would “be allowed to get well under way before the automobiles leave their stations.” Before a crowd of thousands, the Joplin firemen arrived, bells ringing, and extinguished the flames.

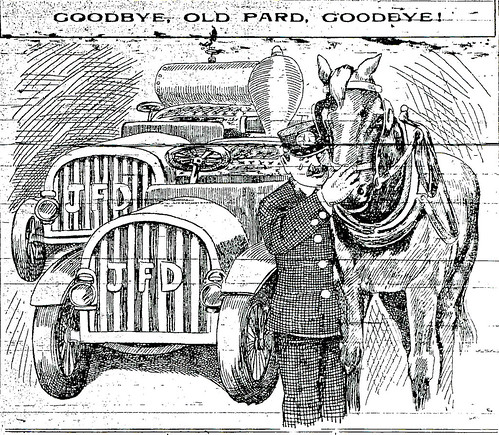

It was a seminal moment for not just Joplin’s fire department, of which the city and its residents intensely proud, but also for fire fighting across the nation. It represented the beginning of the end of the fire horse and the introduction of the modern fire engine. Though, as one editorial cartoon depicted about a week after the tournament, the fire horses, while replaced, were loved and would be missed.

Source: Joplin News Herald