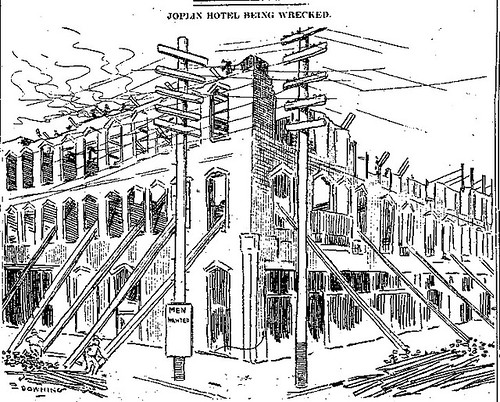

One of the major institutions of modern day downtown Joplin is the Joplin Public Library located in the 300 block between the Third and Fourth streets. The prior occupant of this site was the Connor Hotel. Plans to purchase the block, demolish the Connor, and to erect a new library building began in the 1970’s. The Connor collapsed a day before its scheduled demolition in 1978, and all but a few minuscule pieces of the grand hotel remained on opening day of the new library building in April, 1981. Up until that spring day twenty-nine years ago, the Joplin Public Library had been housed in a Romanesque building, a columned temple of knowledge, a few blocks to the southwest. The origin of it and Joplin’s library system began more than a century ago.

Undoubtedly, the idea to establish a city library came into being not long after Joplin began to establish its schools and a professional class. The dust of the lead and zinc mines was shaken off by a city that pulsed with a passionate desire for progress. In April 1893, a gathering was held at the Young Men’s Christian Association building. It was the first formal meeting of the Joplin Public Library Association. Hamilton S. Wilks was elected president, along with Christopher Guengerich as treasurer, the Reverend E.E. Wilkey as secretary, and C.W. Squire as vice-president. In addition, an executive committee was established with the following women: Mrs. W.H. Picher, Mrs. Clark Craycroft, Ms. Henry Weymen, Lola Spear and Mrs. W.C. Weatherill.

The initial funds to assist in the creation of a library came from a charity event hosted by the Century Club. The club, established only three years previously, was a women’s literary society. Its members embarked on a campaign to create a city library through education and outreach. While a public reading room had been the original idea for the city’s library, it became obvious that an independent library building was needed. The Century Club, and other Joplin literary clubs, claimed victory in the city election of 1901. The months before the vote had been spent campaigning for an annual tax of ten cents for every one hundred dollars appraised for the care and maintenance of a library building. The measure was overwhelmingly approved.

The Library Committee traveled to visit Sedalia's Carnegie Library, pictured here.

This tax was connected to a requirement to form a non-partisan board to oversee the construction and operation of the library. Ten individuals were appointed to the board: William N. Carter, H. H. Gregg, J. D. Elliff, Henry Kost, E. L. Anderson, Reverend Paul Brown, O. H. Picher, Mrs. Ada Goss Briggs, Mrs. Emma Lichliter and Mrs. Hattie Ruddy Rice. Elliff, the superintendent of Joplin’s public schools, was elected president by the board, while the position of board secretary was given to Rice. Shortly after, the board created a committee tasked with overseeing the building and grounds of the future library.

Around May, 1901, that committee explored the possibility of contacting the capitalist Andrew Carnegie. For just under twenty years, the Scotsman offered funds to cities for the construction of libraries. Generally, these donations came upon the promise that the cities guarantee a specific amount of upkeep and continue funding of the institutions. Not long after the president of the board, J.D. Eliff sent off a letter to Carnegie, a reply was received from James Bertram, Carnegie’s personal secretary. Addressed from Skibo Castle, Ardgar, Bertram wrote:

Dear Sir – Responding to your letter of May 6th–If the city of Joplin will furnish a suitable site and pledge Itself to maintain the library at a cost of not less than $4,000 a year. Mr. Carnegie will be glad to provide $40,000 for a suitable building.

Very Respectfully.

James Bertram. Private Sec’y.

The promised sum of $40,000 delighted the board. The question then turned to what the library should look like and where that building should be located.

The discussion of location and design carried on through the months of 1901 and into the first quarter of 1902. It was not until October, 1901, that the board finally came to a decision on the placement of the new library. Proposed locations included the intersection of Eighth and Pearl streets, Cox Park (advocated by the people of South Joplin), and the intersection of Joplin and Ninth streets. The two most popular sites, however, were the intersections of Fourth and Pearl and Ninth and Wall streets. The former were owned by a man named Renfrow and the latter by Christopher Guengerich. According to coverage by the Globe, the board’s primary concern was a location which benefited the entire population of the city.

The board came to a decision on the location on October 21, 1901, when by a vote of 5 to 4, the Ninth and Wall location barely beat out the Fourth and Pearl site. Prior to the vote, attorney and amateur historian Joel T. Livingston offered a presentation, complete with a special map of the city that how the population of Joplin was concentrated. Incidentally, while Livingston claimed to favor no specific site, his analysis of the city’s population placed the epicenter around Eighth and Wall streets. If this swayed the votes toward the Ninth and Wall location, the site was further helped by the testimony of J.W. Freeman, who claimed the location would satisfy the people of South Joplin. It was future Missouri State Senator Hugh McIndoe, as well as Freeman Foundry owner J.W. Freeman, Oscar and C.M. DeGraff, as well as Clay Gregory, who introduced the successful proposition. Thus, the chosen site had strong and influential supporters. As to what type of building would be built at the corner of Ninth and Wall, the discussion continued into the next year.

The Cheyenne Carengie Library design that William Carter favored and became the basis for Joplin's library.

The committee in charge of selecting the design of the library took their task seriously. Initially, a question of whether the city would offer the local Joplin architects was debated. One of the chief proponents against hiring local talent was William Carter, who when asked about the successful architect August Michaelis, sneered, “He learned his business in Joplin.” Carter went on to point out that Joplin had no libraries or similar buildings, and as such, Michaelis had no experience in designing a library. Another supporter of seeking a non-local architect was Ada Briggs, who read a letter written by the president of the Sedalia Library board. Prior to this meeting, members of Joplin’s committee had visited the city to their north to view their Carnegie library. In the letter, the president warned against allowing local architects to use Joplin’s library as an opportunity to learn how to design such a building.

Plans based on the designs of numerous libraries were pushed in an attempt to avoid hiring area architects. One such architectural rendering was the Sedalia, Missouri, public library, which was quickly dismissed for a variety of reasons. It was too big for the lot picked out previously; it failed to include a basement or a separate women’s assembly room; and it cost an additional $10,000 more than Joplin had budgeted. Nevertheless, Ada Briggs described the building as, “beautiful simplicity.”

In lieu of the Sedalia design, Carter suggested the design of the Carnegie library in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Apparently, the news of Joplin’s library design search had spread, as the architect of the Cheyenne library visited Carter the week before to sell him on the design of that building. Carter went so far as to suggest a trip to Cheyenne, similar to that which had gone to Sedalia, but the expense and length of the trip resulted in no support for such an adventure.

In the end, the committee opted to allow local architects to submit plans, based on the fact that a majority of the committee believed that they had already proven themselves with many beautiful buildings about the city. It was even remarked that this was a difference between Joplin and Sedalia. One city had remarkable architecture and the other did not. The committee then reasoned that the advice of the Sedalia library board’s president to seek elsewhere for an architect could be ignored simply because Sedalia did not have any local architects of considerable skill. The plans of three firms were accepted to be voted upon. The three were Garstang & Rea, I.A. Hunter, and August C. Michaelis.

August C. Michaelis, one of Joplin's preeminent architects.

At 2’o clock in the afternoon on February 3, 1902, the committee selected the plan presented by Michaelis. By specification, the design was similar to that of the Cheyenne Library, but not an identical copy. This requirement was probably added to soothe those members, like Carter, who did not want to trust the design to local architects. It featured three floors, a basement, first floor, and second. Located in the basement was to be the men’s reading room, advertised as a place men could visit in or out of work clothes, as well go so far as to enjoy a smoke while perusing book or newspaper. Filling out the basement was a coal room, toilets, and the boiler. Upon rising to the next floor, the visitor found a main hallway of 33 square foot of marble flooring.

On one side of the floor the general reading room was placed connected by doorway to a reference room. Opposite the general reading room was a reading room expressly for children. In addition to a reference room, a room was set aside for librarians and contained a fire proof vault. At the rear of the floor was located a circular stacks, which at the time was supposed to be filled with steel fire proof shelving. The shelves were to be arranged in a circular fashion with the librarian seated in the center and thus with a 360 degree view of the room. The stacks were expected to hold approximately 30,000 books.

August Michaelis' winning design for Joplin's Carnegie Library

Also located on the first floor was a wide double staircase that rose to the second floor. On this uppermost floor was located a room for the women’s club with attached rooms and bathroom. A statuary hall mirrored the hallway below and at the time was thought to be an ideal display area for mineral examples. Separate rooms were set aside for art and for trustees, as well a private reading room. The rooftop was shingled in zinc, though a brief controversy arose when someone claimed architect Michaelis had said otherwise. Michaelis confirmed that the library would indeed have zinc roof tiles. The library was heated indirectly with steam. The library was filled with oak furniture and countertops.

A plan in hand, all that remained was for construction to begin. Part Two will continue the history of the Joplin Carnegie library.

Sources: Joplin News Herald, Joplin Globe, “A History of Jasper County, Missouri and its People,” by Joel Livingston, and Missouri Digital History.