As time passed and mining operations relocated across the area, the Kansas City Bottoms was transformed as “a few factories and mills” dotted the valley and its hillsides. Although there was talk that the Kansas City Southern Railway would build rail shops in the bottoms, the project never came to fruition.

This led to an effort to “more or less isolate the city’s riff-raff of humanity there. It became a sort of ‘red-light’ district, and flourished with gayety, containing gambling houses, saloons, dance halls, and rooming houses.” As Joplin continued to grow, the area grew more desolate, and “buildings were moved, burned, or fell in ruins.” The Kansas City Bottoms soon became a sprawling slum that doubled as a dumping ground. At the turn of the century, an angry mob descended upon the Bottoms and chased out a number of prostitutes who had taken up residence there. Soon the area became populated with African Americans, some of whom had been chased out of Pierce City in 1901, after a brutal race riot ended in the expulsion of Pierce City’s black residents.

A lifelong Joplin resident shared her memories of the Bottoms in a letter to the Joplin Globe:

“Where the [Union Depot] station is now and scattered throughout the valley were shanties occupied mostly by colored folk. This place was known as the Kansas City Bottoms. There was a footbridge over Joplin Creek near where the Union Station is now. Rather than walk around to Broadway, for four years I walked through the Bottoms and came onto Main Street at about A Street on my way to high school.”

“A girl or woman did not dare to cross the Bottoms without an escort. It was not even safe for a man,” the woman continued, “My boyfriend who later became my husband lived on the West side and he never crossed without a weapon. There were often holdups and sometimes murder in the Bottoms. There was no Broadway viaduct then.”

One former Joplin police officer claimed that “policemen were virtually given orders ‘not to bring any of the ‘bottomites’ out.’” This reportedly meant that a police officer should “shoot at the least provocation and shoot to kill.”

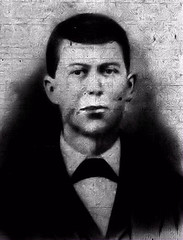

These reputed orders presumably came after the death of Officers James Sweeney and Bert Brannon in 1901 after they were shot and mortally wounded after arresting a gang of vagrants in the Kansas City Southern rail yard and the death of Officer Theodore Leslie who was killed in 1903 while searching the rail yard for a burglary suspect. In 1909, work began on the Third Street viaduct, which spanned the Bottoms to connect East and West Joplin. (To Learn more about the Third Street Viaduct – click here) A year later, work began on the Joplin Union Depot, and a portion of the Kansas City Bottoms was leveled to make way for the expanded railyards and station. (To learn more about the leveling of the Bottoms for the Depot, click here)

By 1915, the condition of the Kansas City Bottoms was as close to a living hell as one could find in Joplin. One account painted a bleak picture of life in the bottoms: “Squatters, trash and garbage haulers, tramps and other transients” moved into the bottoms, living in shacks, shanties, broken down wagons, and tents. Men, women, and children lived in abject poverty. Few outsiders dared enter the bottoms as it had a reputation as, “a most dangerous place. It hardly was safe for a person to enter in daylight. After dark, entry into the hollow by an outsider was practically synonymous with suicide.”

That same year, however, the Kansas City Bottoms would experience a significant transformation for the first time since Sergeant first struck lead.

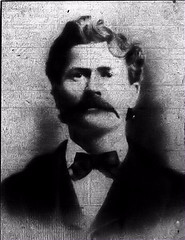

Thomas Gilyard, the black man accused of killing the police officer in 1903, was dragged from jail and lynched by a white mob, despite efforts by some white residents to stop them. After the Gilyard lynching, riots ensued, and a large white mob of men, women, and children demanded that all blacks leave town at once. The mob descended on the black ‘Kansas City Bottom’ neighborhood, firing guns into the night and destroying black businesses and homes. Many black residents who were likely to have been driven from Pierce City earlier, fled Joplin and resettled in Springfield, MO, where yet another racial pogrom unfolded three years later. Over three hundred black residents are believed to have been driven from Joplin, including the family of the great black writer Langston Hughes, who was born in Joplin the year before.