Fires today still make the headlines, but the risk to communities as a whole are not as significant as they were one hundred years ago. Before the emergence of professional fire fighters with modern training and equipment, fires posed a considerable risk to towns and cities populated by wooden structures and defended by brave but untrained bucket brigades. Joplin, like many other cities across the country, learned the hard way of the necessity of a professionally trained and equipped fire department. As one would expect, this story of historic Joplin begins with a fire.

More than thirty years had passed, but the crusty pioneers who witnessed the city’s birth still recalled the first great blaze that occurred in 1874. Only a year old, Joplin was just beginning to build on the success of the mines. For a city in its infancy, the fire was incredibly destructive. Joplin’s volunteer fire department, formed in 1872, was headed by Edward Porter. Porter oversaw a ragtag collection of twenty men who rode on horseback to fires carrying only their axes and water buckets. It was this small, determined band of men who were able to beat back the fire of 1874. Despite the volunteer fire department’s best efforts, an entire block on Broadway was lost, which at the time consisted of two residences and a store room. The only building that survived the blaze was the Masonic Hall which was built of brick. The potential for devastation had been great and had only been narrowly avoided. The limited success of the volunteer fire department convinced Joplin’s city leaders that something had to be done to improve the department’s ability to combat fires.

The answer was a 100 gallon tank filled with a chemical fire suppressant set on the back of a handcart. It was stored in Joplin City Hall which at the time was situated in the bottoms that lay roughly in the middle of town, or rather, between the two former towns of Joplin and Murphysburg that had combined only a few years before. The fire suppressant’s record was mixed. A year after its purchase, it failed to stop a fire that burned down two homes, including one on Mineral Street that belonged to John Allington. This defeat may have been made even more embarrassing as Allington was an influential resident.

A bucket, like the one featured in this photograph from the time period, was one of the main tools available to combat fires.

By this time, Edward Porter had resigned from the position of volunteer fire chief and was succeeded by Frank Williams. It was Williams who was likely in charge when a destructive fire rampaged through near what is now Joplin’s Murphysburg neighborhood. At that time, the main financial district ran from First Street to Fourth with a few homes located south of Seventh Street. The heart of the commercial district was situated at the intersection of Third and Main, but buildings extended south to the corner of Fourth Street and Main, where the Worth Block building later stood. The Joplin News Herald described the fire thus:

“At an early hour one morning two of the buildings in the middle of the block were discovered to be in flames. The alarm was given and the volunteer company turned out. The fire had a good headway and before any efforts could be made to check its spread the center of the row was ablaze.”

It did not take long for the volunteers to realize that the buildings that made up the majority of the block between Third and Main were lost. Built entirely of wood frame construction, a fire could not have asked for any better source of fuel. Firefighters began a valiant effort to save the buildings located at opposite corners of the block as they were considered cornerstones that anchored their respective intersections. Onlookers crowded to watch the fire feed upon the block’s buildings and the fight by the firefighters to save the corner buildings. The firefighters succeeded in their desperate battle but the center of the block was reduced to charred ashes. The next great fire came four years later in 1880 at the famed White Lead Works of Joplin.

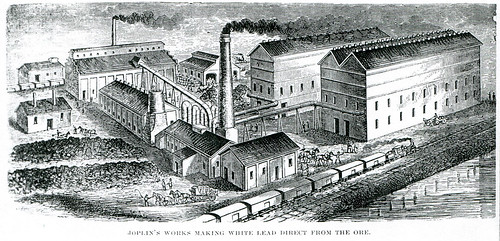

The White Lead Works arose from the idea of E.O. Bartlett, a young professor from Pennsylvania. Bartlett believed the process of smelting lead at the time was a wasteful one that allowed lead carbonate to be lost in the exhaust fumes. To curb waste, Bartlett devised a redesigned exhaust system that tripped a flour-like substance, commonly known as white lead. Bartlett requested the permission of Joplin’s largest lead producers to build his experimental lead factory on their site which would use his new exhaust system. The owners, E.R. Moffett and John B. Sergeant, agreed to the idea. Such was the success of Professor Bartlett’s plan that Moffett and Sergeant quickly implemented the process in their primary lead factories. White lead quickly became a valuable commodity due to its use as a paint pigment and was even used by the United States Navy to paint their ships. It was also commonly used in house paint and posed a great threat to the health of children who might consume the paint flakes.

It was late in the afternoon on April 3, 1880, that a great column of white smoke rose upward into the sky. If that was not enough to garner the attention of the people of Joplin, then the constant shrill screams of the plant’s steam whistles certainly did. Something was wrong. Perhaps someone had stacked the sacks of white lead too tightly together and the cumulative heat of the contents had reached a critical point where the bags had burst into flame. At least, that was the theory settled upon later, but at the moment, all that was known were shouts in the streets of Joplin, “The white lead works are on fire!” The white lead works employed a significant number of the city’s population and an even greater number arrived to watch it burn and look for loved ones that worked there.

Moffett, who was at work at the time, coolly remarked, “Well, she’s gone.” Moffett and Sergeant’s employees had been at their posts with the factory running at full capacity when the fire started. Fortunately, employees were quickly evacuated and Moffett was credited with keeping the crisis in check. All that remained was for the fire department to attempt to save the factory. It was a lost cause before the department even arrived. Joplin’s volunteer firefighters failed due to the enormity and hazardousness of the blaze and they nearly lost the fire department’s chemical tank after it became trapped between two buildings. The overall loss was valued at $20,000, a great sum in 1880.

It was a jarring loss for both the city and its growing economy. The white lead works would be rebuilt, twice its former size, but the city recognized the need to reorganize the volunteer fire department. Volunteer Fire Chief Frank Williams may have stepped down at this point and handed the reins over to Taylor Mayfield, although it is not clear. The city ordered water hoses for the department to use and requested that every business keep a barrel of water and bucket handy. The city also asked for additional volunteers. It would be another fire the same year that spurred the city to continue its efforts to modernize the fire department.

During the late hours of the morning the city’s sole opera house, the Blackwell, erupted in flames. Rouse from their sleep at two in the morning, volunteers valiantly tried to save the large three story structure that lined fifty feet of Joplin’s Main Street. Located just north of the city’s courthouse, the flames could easily leap to the next building and destroy the civil center of the community. Clark Claycroft, a volunteer at the time and later a fire chief, recalled, “We tried our chemical tank but the fire was too much for that, and the bucket brigade did but little better.” As the flames consumed the Blackwell, volunteers recalled the fire hoses that lay inside the fire barn nearby, having arrived only the day before.

“So a bunch of us went to the fire barn, broke open the boxes, and put the hoses together and carried it to the fire. In half an hour, we had two streams of water going.” It was not enough to save the opera house. The Blackwell was lost, but the efforts did protect Joplin’s City Hall which briefly caught fire. The damage was severe and pushed Joplin’s city leaders to continue to improve the volunteer fire department.

Clark Claycroft was selected as fire chief with former city marshal J.W. Lupton appointed as his second in command. Three hose companies were established with their own stations. George Payton, a future fire chief, oversaw Station One located in East Joplin. Station Two stood at Second and Joplin and was commanded by A.B. “Tony” McCarty, and further south, at Seventh and Main, Station Three was overseen by L.A. Fillmore. It was this foundation upon which the Joplin Fire Department was built upon when George Payton became the first paid fire chief at $50 a year. The year was either 1882 or 1884 as various sources dispute the founding date.

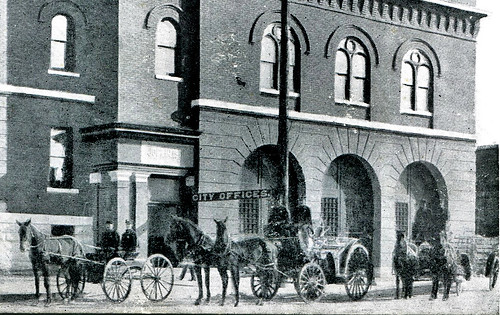

Before the adaptation of the automobile, horse drawn carries were the main method for the Joplin Fire Department to move their fire fighting equipment about the city.

By 1890, the city’s water works had been expanded and improved upon which assisted the fire department with one hundred pounds of water pressure. Up to and past 1900, the companies used horse drawn carriages to respond to fire alarms, but one man would change that. Alfred Webb of Joplin, who operated an automobile livery across the street from one of the fire stations, revolutionized fire fighting. With permission of the fire chief, he mounted one of the chemical tanks and some hose on a motor car and a new era of fighting fires was born. The mechanized apparatus, dubbed “The Goat,” raced swiftly to the scene of fires, and often times was, as Joplin historian Joel Livingston reported, “ready to return when the hose company, drawn by horses, arrived on the scene.” By 1908, the city equipped all its stations with the motorized units and was perhaps one of the first cities to take such a step in the first years of the twentieth century.

The motorized Joplin Fire Department with its two ladder trucks, chemical truck, and fire chief's engine.

This innovation even made the pages of a 1909 issue of Popular Mechanics, which reported on the “up-to-date fire fighting machines.” The four cylinder gas engines of the cars also powered the pumps and worked at a furious 75 horse power. The chief fire engine carried a thousand feet of hose and numerous four gallon tanks of chemical suppressant, in addition to a water pump. The chemical engine, as it was called, hauled a sixty gallon tank, 200 feet of hose, and was powered by only a 25 horse power engine. In addition, the department owned two ladder trucks powered by 50 horsepower four cylinder engines which carried a thousand feet of hose, plus two 30 foot extension ladders.

From a small crew of twenty volunteers with buckets and axes to a modernized fleet of fire engines, the Joplin Fire Department entered the new century. Despite the hazards it had already faced, it was not until 1923 when the department lost its first fireman, one of four honored by the department for their service and sacrifice.

Joplin City Hall, which also housed the Joplin Fire Department station. Note the ladder truck on the right.

Sources: “A History of Jasper County, Missouri, and It’s People,” by Joel T. Livingston, Popular Mechanics, “The Story of Joplin” by Dolph Shaner, “Tales about Joplin…Short and Tall,” by Evelyn Milligan Jones, the Library of Congress, and the Joplin News Herald.