The men and women of Joplin have answered the call of duty for decades. In 1917, Joplin resident James “Jim” Grassham attempted to enlist in the regular army but was turned away. The government, however, had good reason to reject the eager recruit: he was eighty-one years old and was missing his left foot, having lost it to a Confederate bullet in Lancaster, South Carolina.

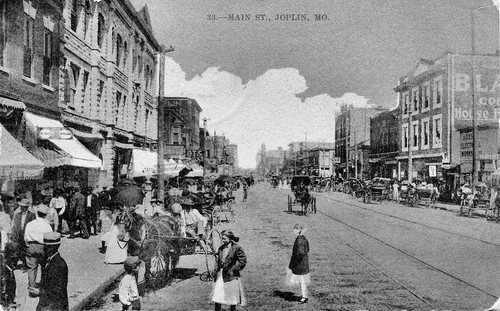

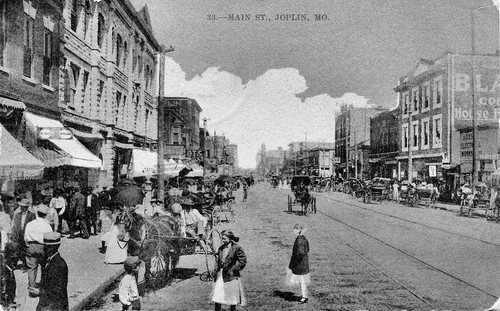

Jim Grassham was a colorful figure who may not have lingered long in Joplin long enough to appear in the census, but he left behind an interesting interview in the Joplin Globe. Grassham was known for selling hot tamales out of a tin pail on the streets of Joplin. He stood out in his white apron, little blue cap, and spectacles. Most prized of all was his “twinkling, happy smile.” Perhaps that’s why many chose to call him “Dad.”

Jim Grassman wandered the streets of Joplin selling his hot tamales.

According to Jim, his father arrived in American in 1777 with the Marquis de Lafayette. His father, described as a “mere boy,” was allegedly at Yorktown being treated in a field hospital for wounds when the British General Cornwallis surrendered. The elder Grassham was unable to return to France due to his wounds. A Jewish Virginia revolutionary soldier took Grassham in and nursed him back to health. Grassham courted and married the man’s daughter. Together the couple had several children, including eight boys.

Jim told the reporter his father lived to be 104, which might be attributed to the fact that he drank wine he imported from his relatives back in France. He said, “Father didn’t talk much about the revolution. There were many important things happening after the revolution that seemed more important to him than the revolution itself. The development of the was his hobby and he advised all his boys to go west and get land and we all went to Kentucky and then to Tennessee and some of us to Arkansas after the war.”

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, four of the boys joined Union forces, while the remaining four signed up with the Confederacy. At the age of 28, Jim left his wife and four children and joined Company I of the Third Kentucky Cavalry (US).

After serving four years, four months, and twenty-nine days without a scratch, Jim and his fellow cavalrymen were skirmishing with Confederate troops at Lancaster, South Carolina, when a bullet “stung” him in the ankle. He said that the wound did not hurt, but his pride must have for he was taken prisoner after he was shot. He was taken by Confederates “to Salisbury and later to Libby prison, and then was taken out on a prison ship off Annapolis and there he was when the war ended.” It was then that blood poisoning set in. Because he did not receive proper medical attention, Jim’s foot had to be amputated. According to Jim, he did not “allow the doctors to give him chloroform or any kind of ‘dope’ and the operation didn’t hurt until they ‘cut the leaders’ (tendons) and then he ‘just naturally raised hell with them.’”

After the end of the war, Jim received a fifty dollar pension from the government and a rubber foot. He took the advice of his father, who had always advised his sons to go west, and settled in Arkansas. Over the years, he married four times and had fourteen children. His last wife, who was seventy-eight, had been blind for two years when the Globe reporter interviewed Jim. He said he owned some farms in Arkansas, some Liberty Bonds, and sold the tamales “just to be doing something” as well as support his wife, tubercular son-in-law, daughter, and several grandchildren. One of his daughters had eleven children; another had nine, all girls. At least four of his grandsons had enlisted in the regular Army, two of whom were bound for France as part of Pershing’s American Expeditionary Force.

When asked about his long life, Jim said he didn’t use tobacco, although he used to before “the doctor made me cut it out several years ago and I never went back to the habit.” He still took a nip of whiskey, usually during rainy weather. Jim claimed that he had suffered a bout of pneumonia but whiskey helped him pull through it “like a young colt.” Jim observed that a person should keep busy and be an optimist.

Jim reflected, “I’ve been busy ever since I was a kid. Every member of my family has been the same way. My father was a hard worker, a great ‘producer,’ as we used to call a man who succeeded. My brother, who is 89 years old, works at blacksmithing and he stands at his anvil every day. He lives in Tennessee now. I think its hard work and a cheerful disposition that keeps anyone going. I don’t feel that I’ve aged a bit in fifty years. I don’t think much of fads about what you eat or drink to live long.”

He then told the reporter he wasn’t sure if he was going to stay in Joplin much longer due to the rainy weather as he “doesn’t like too much rain.” Although he lived in Chitwood, Jim could be seen walking the streets of Joplin any night “ready to exchange a witticism or a laugh with anyone.”

Source: Joplin Globe