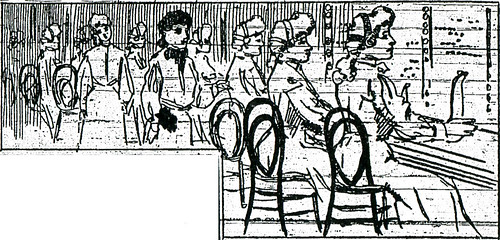

In 1910, the Joplin News-Herald ran a story about the advantages of working as a “Hello Girl.” The News-Herald remarked that while it might not be fun to “sit up to a switchboard and come in contact with the varying dispositions of several hundred people each day” there were “some things about the work of the central girl at the Home Telephone company’s office in this city that probably come to no other working girls in town.”

Despite hearing about “heartless corporations” the News-Herald assured readers that this was not the case with the Home Telephone Company located in a building on Joplin Street. Since 1906, girls were treated to an on-site “culinary department and lunch rooms.” The News-Herald reporter, unable to curb their enthusiasm, gushed, “A lunch room and a kitchen in the telephone plant!” On “pleasant days” a light lunch was served, but when the weather turned bad, regular dinners were served that were, “equal to those of the best restaurants in town.” Girls were guaranteed a free lunch twice a day.

When the operators were at work on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and other holidays, the company served large dinners in the company dining room so that the girls could at least have a hot dinner during the holiday. Empty stomachs and “improper food”, the company believed, could affect an employee’s disposition. Lunches and holiday meals meant, “congenial employment, pleasant surroundings, and the saving of considerable money in the course of a year.”

Even more astonishing, at least at this time in history, was the fact that the company also had “baths, individual lockers, and a rest room, or sitting room” that was overseen by a “regularly employed matron.” Should a girl seem exhausted or ill, she would be sent to the rest room or home. Mrs. R.L.Whitsel, the company’s matron, was hailed as, “experienced and efficient.”

If the weather was nasty, the company paid for closed carriages to pick up girls at their homes to bring them to the office. Once their shift was over, a carriage would transport the girl safely back to her home. The company’s management realized that “healthy, happy, and well cared for girls are more likely to be cheerful and pleasant to their patrons and more prompt in service than girls who are overworked and neglected.” Wet clothes were considered “hard on the disposition and health of the girls and the telephone company prefers to have its employees happy and cheerful, even if that means occasional bills for carriages.”

Given the number and types of jobs available in Joplin at the time, it appeared that if a young woman could secure a job as a Hello Girl, she found herself with a relatively comfortable means of income. It also represented a time period when society felt that young women deserved an extra amount of protection from the theoretical evils of the business world, where vicious characters lurked to take advantage of young, innocent women. Never the less, this legacy of care from the Victorian world seemed to offer some of the women of Joplin a safe and inviting place to work.

Source: Joplin News Herald, 1910