Previously, we took a short tour around downtown Joplin with photographs of some of the surviving painted signs of Joplin’s past. Out of the destruction of the May 22 tornado and the consequential demolition, we discovered a new addition to the club, featured below; a sign from the past.

Review of “Joplin” by Leslie Simpson

Leslie Simpson, the director of the Post Memorial Art Reference Library, writes in the epilogue of Joplin, “This book is my love letter to the city of Joplin, of which I am proud to be a citizen!”

Simpson’s latest book is a wonderful love letter to Joplin, a fine work that covers the history of the city from its establishment in 1873 to the present day. It is a lavishly illustrated postcard history of the city accompanied by detailed, informative captions. The book provides readers with an understanding of the people, places, and events that shaped Joplin into the city that it is today. Simpson does an excellent job of balancing the past and present so that readers are taken through Joplin’s early years, subsequent growth, Route 66 years, up until the time of the tornado.

The book is helpfully divided into nine sections that cover different topics such as mining, industry, residences, schools, churches, and hotels. Although one might expect that because the book is postcard history the book might be poorly researched, it is not. The captions for each illustration are insightful, well written, and historically accurate. Each illustration has been carefully chosen and offer unique glimpses into Joplin’s social, cultural, religious, and architectural history.

Sadly, Simpson’s work illustrates just how many Joplin buildings and other landmarks have been lost to the ravages of time, benign neglect, or lack of vision. Our advance copy notes that “Profits from the sale of this book will be donated to the Joplin Chamber of Commerce Business Recovery Fund” so you can be assured that your money will go to a good cause. We also recommend that you might consider giving a donation the Post Memorial Art Reference Library.

Those who own Leslie Simpson’s prior works may recognize some, but not all of the images used, however all offer entertaining glimpses into Joplin’s past. For those who have and enjoyed the above mentioned Now and Then and Again, they have a great companion to Joplin.

Joplin is a well written and illustrated history of Joplin, Missouri. It is accessible to readers of most ages and is a enjoyable read for those who enjoy local history, the history of Joplin, and illustrated histories. Hopefully it will leave most readers with an even greater appreciation for the City that Jack Built.

Joplin, $21.99, Arcadia Publishing

Available at Hastings and through the publisher at www.arcadiapublishing.com

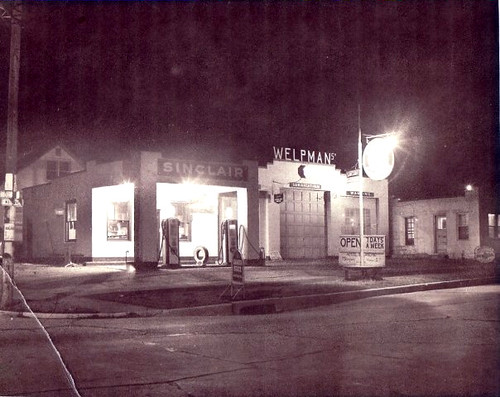

Welpman’s Service Station

From time to time, folks offer to generously share a bit of the Joplin history in their possession. The photograph of Welpman’s Service Station above is one such example. The image captures the building at night in the 1950’s, when it was owned by Gary Welpman. Happily, the building still stands today.

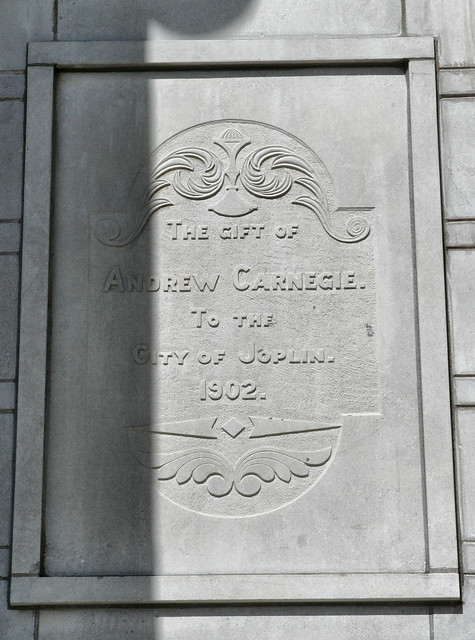

Joplin Carnegie Library – Photographs

Last summer, Historic Joplin wandered about downtown with a camera and one of the stops was the Joplin Carnegie Library, the former home of the Joplin Public Library. Below are a few of the photographs from that visit. Previously, we’ve brought you the history of the library building (here and here), as well a glance at how the library has changed or not changed over the century since its construction. Enjoy!

First Church of Christ Scientists For Sale!

A drive past the intersection of 16th and Wall Street will take you by the First Church of Christ Scientist Church completed in 1906 and now the home of Faith Fellowship. A quick glance will also reveal a for sale sign next to the stately house of worship. It’s not often that 106 year old buildings in Joplin go up for sale, much less one that is a church. We took a few quick snapshots of the church and for those interested to learn a little more about the property, you can find the church’s listing right here.

What If: Main Street Looking North

Brown, August 5th 2011 |This Building Matters: Louis Curtiss’ Joplin Legacy

In the past we have written posts about the construction of Joplin’s Union Depot. Now we would like to celebrate the life and work of its architect, Louis Curtiss. Sadly, his legacy is in peril. Of the over 200 buildings and projects that Curtiss designed, only 34 remained in existence by 1991. Of the 34 buildings, 21 were in Kansas City. Joplin is incredibly fortunate to have the Union Depot among its built landscape. If you care about history, if you care about cultural memory, and if you care about historic preservation you can appreciate Curtiss and Joplin’s Union Depot.

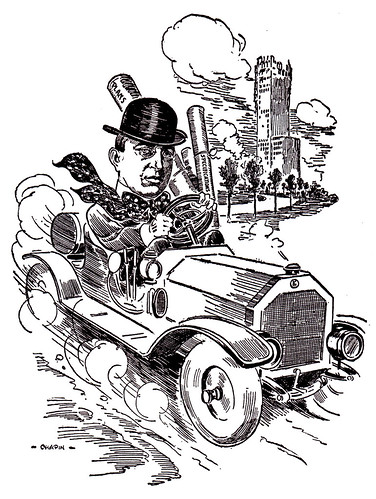

A native of Belleville, Ontario, Canada, Curtiss arrived in Kansas City, Missouri in 1887 at the age of twenty-two. Throughout his career, Curtiss was an enigma. He never discussed his life, never married, never had children, and ordered that his personal papers be burned upon his death. Curtiss was an incredibly colorful character. He loved fast automobiles: he would often roar around the city in a Winton runabout which, at the time, reportedly topped out at an amazing 30 mph. He loved women; he cut his own hair; and claimed to have studied architecture at University of Toronto and the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, although historians have been unable to confirm this due to spotty recordkeeping.

Curtiss briefly worked as a draftsman in the architectural firm of Adriance Van Brunt. He then left to form a partnership with Frederick C. Gunn. Together Curtiss and Gunn designed a large number of courthouses across the Midwest and South. The current courthouse for Henry County, Missouri, is a Curtiss and Gunn creation. Regrettably, the original tower on the courthouse was removed in 1969. The Curtiss and Gunn designed courthouse in Gage County, Nebraska, still has its original tower. The partners also designed courthouses in Tarrant County, Texas; Cabell County, West Virginia; and Rock Island County, Illinois (its roof dome was removed). Even more interesting, they designed St. Patrick’s Parish Catholic Church in Emerald, Kansas.

After ten years, Curtiss and Gunn went their separate ways. Curtiss traveled abroad and studied architecture, but eventually returned to Kansas City. He designed a private residence dubbed “Mineral Hall” which survives today on the campus of the Kansas City Art Institute. Curtiss designed other private residences and commercial buildings at this time. Mineral Hall Link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mineral_Hall Note that the doorway is Art Nouveau in style.

Curtiss’ Folly Theater (now the Standard) still stands in Kansas City after construction finished in 1900. You can read about its colorful history here.

While living in Kansas City, the young architect had the good fortune of meeting Bernard Corrigan, a fellow Canadian who was a partner in Corrigan Brothers Realty Company, and for fifteen years the two worked together on a variety of projects.

Curtiss’ first large project, the Baltimore Hotel, was commissioned by the Corrigan Brothers. The hotel was located in downtown Kansas City at the corner of 11th and Baltimore. It was later demolished in 1939. Curtiss’ next major commission was the Willis Wood Theater. Located next to the Baltimore Hotel, the two were connected by a tunnel that was nicknamed “highball alley.” The theater was destroyed by fire in 1917. One of Curtiss’ residential masterpieces, the Bernard Corrigan House, still stands today. The house is a mesmerizing blend of Prairie, Arts and Craft, and Art Nouveau features. You can view pictures here and also here, too.

Curtiss established another fruitful partnership, although it was not with an individual, but with a company: The Santa Fe Railroad. Curtiss designed depots and office buildings for the railroad company all over the United States. He subsequently began designing buildings for the Fred Harvey restaurant system. During this time, he designed the Clay County State Bank, which is now the Excelsior Springs City Museum.

As years passed, he continued to design railroad depots, hotels, and private residences. In 1910, work began on Joplin’s Union Depot, a Curtiss creation. He also designed Union Station in Wichita, Kansas, which had survived the years since its completion in 1913. Interestingly, he designed the “Studio Building” to serve as his studio. Curtiss lived in an apartment in the building which coincidentally adjoined a burlesque theater. According to one individual who was interviewed years later about Curtiss, there was a balcony entry into the theater accessible only through Curtiss’ apartment, through which he could attend performances.

Beginning in 1914, Curtiss fell upon hard times. Many of his major clients began to pass away and the demands of World War One upon American society made new construction grind to a halt. Curtiss’ architectural style fell out of favor as new and reinvigorated styles became popular. He did achieve success with his work in the Westheight Manor subdivision of Kansas City, but he never regained his pre-war popularity. One of the residences he built in Westheight Manor is the stunning Jesse Hoel home: Historical Survey of the Westheight Manor Subdivision and Flickr Photo of the Hoel residence.

Another Westheight Manor home Curtiss designed was that of Norman Tromanhauser.

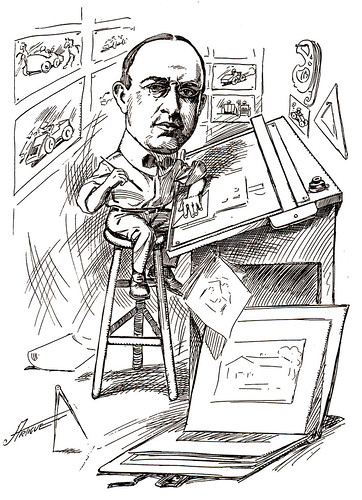

By 1921, Curtiss ceased to produce new architectural designs. Within a few years, on June 24, 1924, he died in his studio at his drawing board at the age of fifty-four. He was buried alone in Mount Washington Cemetery

The Joplin Union Depot matters.

Sources: Stalking Louis Curtiss by Wilda Sandy and Larry K. Hancks, Kansas City Public Library, Others.