Local newspaper baron Alexander Washington “Kit” Carson was one of the most influential individuals in the early development of Joplin. While he was not a capitalist like Thomas Connor, Carson left his own indelible mark on the city he called home.

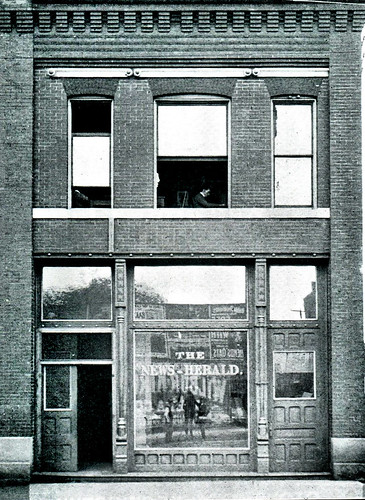

The red-headed Carson was born near Cadis, Ohio, in 1842. During the Civil War, he served with Company C of the Forty-Third Ohio Volunteer Infantry. After the war ended, he headed west, and taught school at Marshfield, Missouri. Carson left Marshfield a few years later and arrived in Joplin where he began publishing the Joplin News-Herald in February, 1877. Years later Carson, a lifelong bachelor, was still living in his apartment located in the News-Herald building located on Fourth Street. He could often be seen sitting outside the building in a chair reading his old paper. Carson’s friend John Power was an early resident of Joplin and recalled both Carson and the glory days of Joplin’s journalism community in a newspaper article.

Together with Columbus “Lum” Farrar, Carson founded the Joplin News-Herald, and soon became sole owner after Farrar found journalism to be hard work. Carson bought out Farrar’s interest in the paper and remained sole proprietor. He put in long hours as the News-Herald was the morning paper. Carson stayed up all night furnishing the copy, proof-reading, making up forms, and then printing the paper on an old Washington hand-crank printing press. By the time he sold the paper in 1888, the News-Herald had become “hard to kill” with a first rate printing press and loyal readership. After he sold the paper, he became known for his eccentric, yet gentle personality.

Power related one story in which Carson had a number of young calves in his lot. A man passing by happened to see the calves and asked Carson if they were for sale. Carson replied that they were. The man offered $7 for each calf and Carson agreed to sale them. The buyer then told Carson he had to go uptown to get cash and would return shortly to pay for the calves. Upon the man’s return, he began to feel the calves. Carson, suspecting the man was a butcher, asked if he was indeed a butcher. The man replied that he was. Carson replied, “You haven’t money enough to buy those calves…I would about as soon allow children to be killed.”

On another occasion, Carson sold some pedigreed hens worth $2-$5 apiece to a woman for only 25 cents apiece, thinking that she would use them for eggs. He stopped by the woman’s house a few days later only to discover that she had eaten all of the chickens. Carson, in tears, remarked that had he known she was going to eat them he would have kept them, as he had hand-raised the chicks after they were orphaned.

He also had a soft heart when it came to his friends. Power recalled on one occasion when the two were out in Carson’s buggy and stopped to visit one of Carson’s old friends. The men talked briefly and then Carson pulled away, remarking that his friend’s coal bin was empty. Carson’s next act was to order a ton of coal and have it delivered to his friend’s residence.

Upon Carson’s death, Peter Schnur (who would die the next year) remarked, “Although we were business competitors, he was one of the closest personal friends I had. The squarest man in business, honest, trustworthy, companionable, fearless but gentled, the heat of campaign nor the struggles of business competition never affected the strong friendship between us.” He ended by observing, “Mr. Carson was a man of peculiarities.”

And peculiar he was. In his will, A.W. Carson specified that $1,000 of his money be spent on the dissemination of Mark Twain’s “How to Be a Gentleman.” The only problem was is that no such work existed.

Mark Twain, whose non-existing idea of a gentleman was the focus of Carson's will. Library of Congress.

A few days after Carson’s will was read, Twain was asked about his advice for the young after he finished a speaking engagement at the Majestic theater in New York City. He remarked how the subject often came up, “Here is such a request,” Twain said, “It is a telegram from Joplin, Mo., and it reads: ‘In what one of your works can be found the definition of a gentleman among the young.”

Twain declared he had never attempted to define a gentleman, but added, “I might say that a gentleman was — well, a biped who is not a lady. That might take it all in, but it seems to me that there was a verse read here from the Bible about justice, mercy — what was that third one? yes, kindness, Oh, yes, kindness.”

He then concluded by offering a few remarks about his former servant Patrick McAleer who had recently passed away. Twain concluded, “In all the long years Patrick never made a mistake. He never needed an order; he never received a command. He knew. I have been asked for my idea of an ideal gentleman, and I give it to you — Patrick McAleer.”

As for A.W. Carson, he left behind many friends who were faced with one last peculiar act of an eccentric man who did much to contribute to the success of Joplin.

Sources: Joplin Globe, Joplin News-Herald