Recently, Joplin Museum Director Brad Belk chose to write briefly about Harry Francis Craft for the Joplin Globe. Craft was not the first nor last baseball manager to pass through Joplin either on the way to the Major Leagues or on their way after. Perhaps one of the earliest baseball managers was “Honest John” McCloskey.

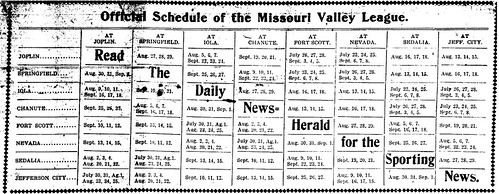

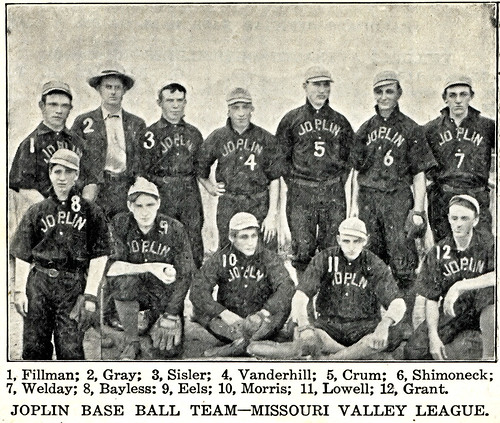

McCloskey rolled into Joplin in 1887. 1887 was the year that the News Herald declared that Joplin finally decided to become serious about baseball. This resolve was put into effort by the construction of a baseball field at the end of a mule drawn trolley line on west 9th Street. The city advertised for players, apparently finding none at home who met their own criteria, and ended up hiring a number of players from the “Kerry Patch” area of St. Louis. At the same time, the paper noted, a boom in some eastern Kansas towns had led John McCloskey to managing in Arkansas City.

Successfully defeating the Kansas towns, McCloskey brought his team to Joplin and thrashed the hometown heroes. Henry Sapp, who had made money mining lead and later zinc, and had been a driving force behind the St. Louis hiring, quickly fired the team and promptly bought out McCloskey and his Arkansas City team. Victory followed for Joplin until summer came to an end and fall grew closer to winter. Eager to keep playing, McCloskey raised enough support among Joplin businessmen to fund a tour of Texas. Purportedly, the Joplin players may have been among the first to assume the title of “Joplin Miners” with the team name stitched on the front of their uniforms. In the process, the Joplin team defeated two national league teams traveling through the state, one from New York and the other from Cincinnati, and may have also contributed to the establishment of a Texas baseball league.

In the late 1890’s, McCloskey returned several times to Joplin to field a team. One team, the Giants, competed against the Bloomer Girls in 1898. A few years later, McCloskey found himself the manager of the St. Louis Cardinals from 1906 to 1908. By his later years, the manager found himself without the success that had brought him a job in Joplin. Friends helped out McCloskey by contributing money to purchase the on and off again Joplin manager a home in Louisville, Kentucky.

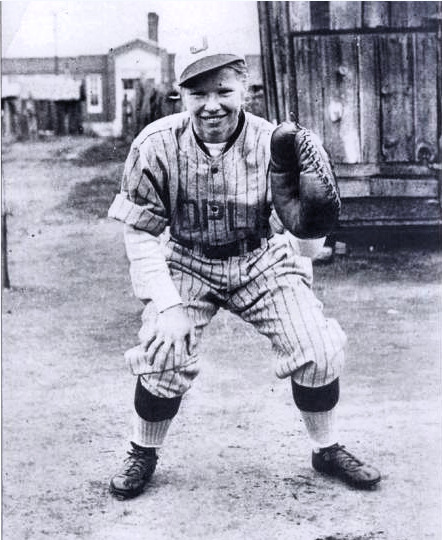

Perhaps Joplin’s most successful baseball manager was Charles “Gabby” Street. Street was a son of Alabama and had a baseball career cut short by what Joplin newspaper man, Robert Hutchison called, “overindulgence in the bottled stuff.” Hutchison counted Street a friend and met with him and others every weekday morning during the off season to share their passion for the sport. One of the other regulars was Joe Becker, namesake of Joplin’s Joe Becker Stadium. Hutchison noted that Street earned the most fame as a player for catching a ball “thrown” from the top of the Washington Monument and as the catcher for Walter Johnson, a fellow teammate on the Washington Senators.

Street managed the Joplin Miners from 1922 to 1923, the former season being the one where the Miners won the Western Association championship. The success in Joplin lead him away from the city, but he later returned to make a home and to invest in real estate. He kept this home, according to Hutchison, before his major league appointment as manager of the St. Louis Cardinals. At the Cards, Street managed from 1929 to 1933, taking the team to the World Series twice. Hutchison aptly described the two trips, “His Redbirds lost the 1930 World Series to Sly Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics, four games to two. They met again the next year and the famed Gas House Gang ripped up the basepaths for a victory in seven hard fought contests.”

The World Series pennant was the highlight of Street’s career. Soon after he was let go from the Cardinals and only returned to the show one last time to manage a losing St. Louis Browns. As Hutchison then recalls, “Gabby came home to stay.” Later on, Street did return to St. Louis, but to provide color commentary for the Cardinals instead of coaching. At this time, a future radio commentator worked with him, Harry Caray. When Street passed away, he was buried in Mount Hope cemetery along with many of the other notable names in Joplin’s past. West 26th Street is named after the baseball coach, who likely will be remembered as the most successful of the baseball managers to find their way to Joplin.

Sources: Joplin News Herald, Robert L. Hutchison’s “Deadlines, Doxies & Demagogues,” and Baseball-reference.com.